Earthly Powers: The Children of God and Jonestown

-

Graham Foster

- 2nd July 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

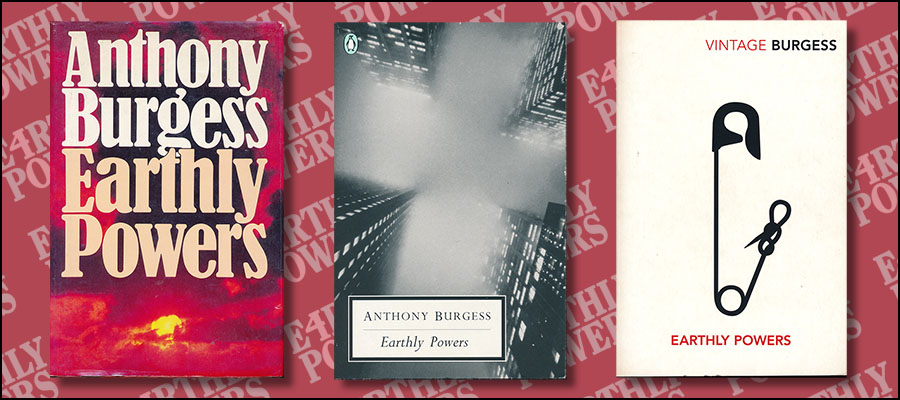

We reveal a gruesome inspiration behind Anthony Burgess’s novel Earthly Powers: the Jonestown suicide cult leader Jim Jones.

One of the pivotal events in Earthly Powers is the establishment and violent dissolution of Godfrey Manning’s religious cult, known as the ‘Children of God’.

Although this cult seems to be well ingrained in the narrative of the novel, it appears that it came about late in its composition. Burgess began writing the novel in 1970, but the details of the Children of God were not added until November 1978, when the mass suicides of the People’s Temple cult at Jonestown became international news.

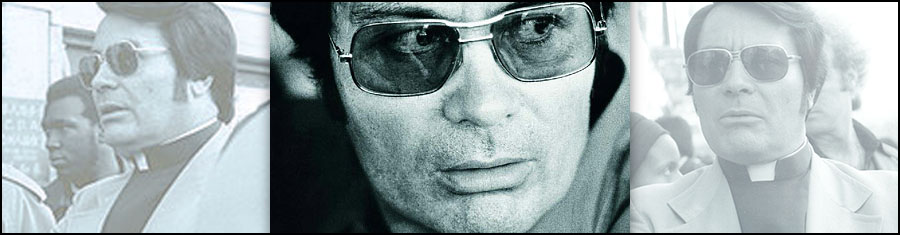

The Reverend Jim Jones (above), the founder of the People’s Temple, began his life as a preacher with the Methodist Church in the Midwest of the United States, though his sympathetic view of Communism and his desire to create a socially diverse church led him away from more traditional forms of religion. Eventually moving to California, Jones began to describe himself as the reincarnation of Jesus, Gandhi, the Buddha and Vladimir Lenin, and he stated his desire to create a new Eden on Earth.

The Reverend Jim Jones (above), the founder of the People’s Temple, began his life as a preacher with the Methodist Church in the Midwest of the United States, though his sympathetic view of Communism and his desire to create a socially diverse church led him away from more traditional forms of religion. Eventually moving to California, Jones began to describe himself as the reincarnation of Jesus, Gandhi, the Buddha and Vladimir Lenin, and he stated his desire to create a new Eden on Earth.

But in contrast to this apparent egomania, Jones also involved himself in the civil rights movement, and in 1977 he was awarded the Martin Luther King Jr Humanitarian Award. It was not until the founding of Jonestown in Guyana, also in 1977, that Jones became internationally known. Separated from civilisation, the People’s Temple became more corrupt, with revelations of Jones sexually abusing male and female members of his congregation, and becoming more draconian in his behaviour. This descent was punctuated by acts of extreme violence, including the murder of US Congressman Leo Ryan (below), and eventually the mass suicide of the inhabitants of Jonestown.

More than forty years after the events of Jonestown, its legacy still has powerful resonances. The phrase ‘to drink the Kool-Aid’, a reference to the poisoned fruit drink (actually Flavor-Aid) that Jones fed to his followers, has entered the language to refer to anyone who is unquestioningly obedient or brainwashed. The scale of the tragedy not only inspired Burgess to include a suicide cult in Earthly Powers as an example of American evil, but also inspired responses by other writers.

Burgess was certainly familiar with ‘The Suicides at the Temple’, an article by Umberto Eco (pictured below), first published shortly after the deaths at Jonestown. Eco establishes Jonestown as a logical evolution of the millenarian cults which have flourished throughout history. More pertinently to Earthly Powers, he makes an association between Californian experience and the People’s Temple: ‘California is a paradise cut off from the world, where all is allowed and all is inspired by an obligatory model of “happiness” (there isn’t even the filth of New York or Detroit; you are condemned to be happy). Any promise of community life, of a “new deal”, of regeneration is therefore good. It can come through jogging, satanic cults, new Christianities.’

In an article published in 1971, Burgess was already thinking about the role of American culture in the evolution of Christian ideals: ‘America was built on rejection of the past. Even the basic Christianity which was brought to the continent in 1620 was of a novel and bizarre kind that would have nothing to do with the great rank river of belief that produced Dante and Michelangelo. America as a nation has never been able to settle to a common belief more sophisticated than the dangerous naïveté of the Declaration of Independence. “Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” indeed.’

Godfrey Manning, the leader of the Children of God in Earthly Powers, is modelled closely on Jim Jones. He is a charismatic leader who has mysterious reserves of cash and makes his name with philanthropic acts before setting up his commune in the Californian desert. Like Jones, Manning is also in thrall to the preacher Father Divine, who believed he was God and who Toomey describes as ‘dispenser of love and chicken dinners.’

The suicides of the Children of God are clearly linked to the similar events at Jonestown, but Burgess changes the symbolism by having the poison administered as part of the Eucharist. He describes the scene: ‘Manning presided over the almost instantaneous deaths of seventeen hundred adults. The children did not die: they spat out the bitter host. He saw from his podium what he had often tried to imagine, his imagination being much assisted by pictorial evidence of Nazi camp slaughter.’ This comparison is not accidental. Throughout his depiction of the cult in Earthly Powers, Burgess relates it to the cruelty and bloodlust of Nazi Germany, and he implies that there are connections between these two manifestations of human evil.

Burgess’s representation of Jonestown in Earthly Powers seems to have been one of the first fictional responses to these events. This may also explain why Earthly Powers lacks the distance to be found in some later accounts.

Other writers followed Burgess with their own responses to the tragedy of Jonestown. Burgess owned a hardback copy of Shiva Naipaul’s Black and White (1980), and his friend Wilson Harris (above) retold the story of the People’s Temple in terms of colonial trauma in his novel Jonestown (1996).

For Burgess, the story of Jim Jones and the People’s Temple was a thematically resonant addition to Earthly Powers. It provided him with a conclusion which complicates the discussion of good and evil, and allows the novel to ask hard questions about the role of a God who is seemingly indifferent to human suffering.