Burgess and the annotated Mary Queen of Scots

-

Anna Edwards

- 12th July 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

-

tagged as

- Archive

- Film

- Manuscripts

- Mary Queen of Scots

Not every project realises its full potential, and documents in the Burgess archive point towards a film project which, like its subject, faced a premature end.

In December 1968, Burgess received a letter from his literary agent Deborah Rogers, with an update on incoming correspondence.

Burgess had left England in October to begin a new life in Malta, and Rogers had struggled to keep in regular contact with him as he made the slow journey across Europe in a Bedford Dormobile (a motorised caravan). She was relieved to hear from him after a few weeks of silence while he was travelling.

Burgess — ‘Dearest John’ to his agent — was much in demand, and there was a lot to discuss. Warner Brothers had commissioned a second draft of the script for The Bawdy Bard, a proposed musical about the life of Shakespeare. There were negotiations about a possible film adaptation of Inside Mr Enderby and Enderby Outside; discussions with Si Litvinoff about the film script of A Clockwork Orange; and news about a range of domestic matters, such as Burgess’s application for residency in Malta.

Much of this is well documented, but Rogers’s closing remark — ‘Meanwhile, have you read the script from Sandy MacKendrick? I hope it arrived safely’ — points to a project which is unknown to most readers.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, Alexander ‘Sandy’ MacKendrick (1912-1993) was highly regarded as a postwar film director and screenwriter. He had directed classic Ealing comedies such as Whisky Galore! (1949), The Man in the White Suit (1951), and The Ladykillers (1955), before moving to Hollywood in 1955. His first American film, Sweet Smell of Success (1957), starring Tony Curtis and Burt Lancaster, was a critical triumph, and it was followed by three more feature films in the 1960s.

In 1967 MacKendrick returned to London to work on a new film for Universal about Mary, Queen of Scots, and it was in relation to this project that he sought Burgess’s help.

MacKendrick started to develop a film about Mary Stuart (the mother of King James I) in the 1950s at Ealing Films, but it was vetoed as being ‘too disrespectful to royalty.’ Notes in the Burgess Foundation’s archive provide a sense of MacKendrick’s vision. He writes about his ambition to retell the story as a kind of western or gangster movie:

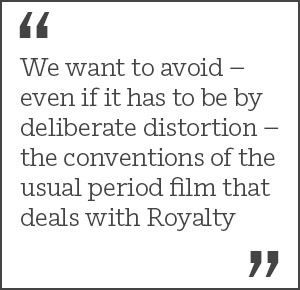

‘We want to avoid — even if it has to be by deliberate distortion — the conventions of the usual period film that deals with Royalty.

This is a point on which I am somewhat fanatical. Unless presented in this totally “unregal” way, the girl’s story does not make sense.’

Warring factions are ‘as close as hoodlums behind a Mafia chief’ and sixteenth-century Scotland is said to be ‘Frontier Territory’.

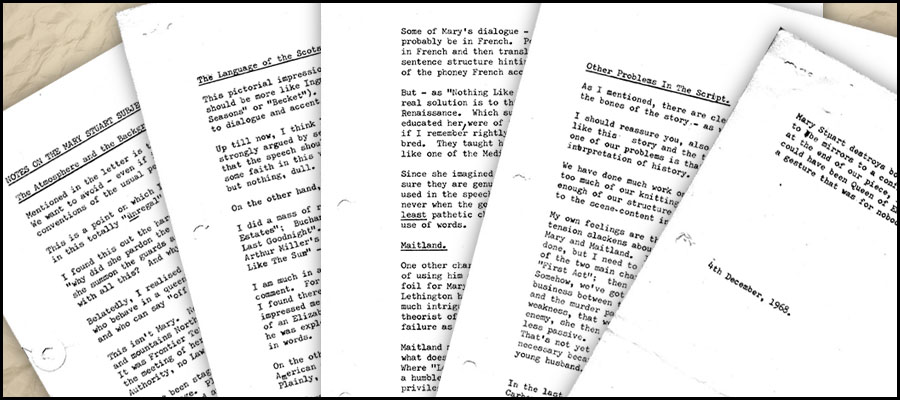

In five pages of notes, MacKendrick discusses aspects such as ‘The Atmosphere and the Background’, the characters of Mary Stuart and William Maitland of Lethington, ‘The Language of the Scots Characters’ and ‘Other Problems with the Script’.

He was particularly eager for Burgess to help with the film’s dialogue. Although MacKendrick had a firm vision for the overall look and feel of the film, he wrote: ‘I confess I am a lot less secure when it comes to dialogue and accent.’ He was unconvinced by people who advised him to adopt spare and simple speech, in keeping with the analogy of a Western, and he asked for Burgess’s input.

MacKendrick had recently read Burgess’s novel Nothing Like the Sun, which tells the story of Shakespeare’s life in a language designed to sound authentically Elizabethan while appealing to the modern ear. MacKendrick told Burgess that he was ‘much in awe of your mastery of language’, and he believed that Burgess was the only man who could to resolve the problem of how to ‘recreate the tongue that seems more real than the real.’

MacKendrick was concerned that Burgess might have been reluctant to get involved in the project at a late stage in its development. It is clear that Burgess was sufficiently interested to begin work on editing MacKendrick’s 132-page script.

A copy of the script, with annotations by Burgess on ten pages, survives in the Burgess Foundation’s archive. Further scripts by Burgess, Jay Presson, and MacKendrick form part of the British Film Institute National Archive. A letter from Deborah Rogers to Burgess in April 1969 refers to payment by Universal for his work on the project.

In 1969 Mary Stuart was due to start production, but the studio fell victim to the late 1960s’ recession in British film production, and Universal closed its London office, cancelling all current projects. MacKendrick decided to retire from filmmaking, and he dedicated the rest of his life to teaching, beginning in 1969 as Dean of the Film School at the newly established California Institute of the Arts (CalArts).

But the story of the Mary Queen of Scots project does not end there. In 2018 BBC Radio 4 broadcast an adaptation of an unproduced screenplay by MacKendrick and Jay Presson Allen, as part of their ‘Unmade Films’ series.