Falling for Falstaff: the Shakespearean archetype that fascinated Anthony Burgess

-

Sam Jermy

- 30th September 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

As he approaches the end of his research into Anthony Burgess’s 1973 Shakespeare lectures, PhD student Sam Jermy casts a light on Burgess’s fascination with the boorish knight Falstaff — including the unpublished Sir John Falstaff va alla Guerra.

In his lecture course ‘William Shakespeare: The Man and His Work’ delivered at City College New York in 1973, Anthony Burgess exalts Sir John Falstaff as ‘a fat man, a coward, a man with absolutely no virtues, yet intensely loveable.’

This fascination with the paradoxical and enduring legacy of Shakespeare’s rebellious knight takes centre stage in Burgess’s lecture on Elizabethan theatre in 1597, as well as in his wider creative and intellectual engagement with Shakespeare across his career. To Burgess, the Shakespearean essence which persists is the Falstaffian.

The recurring appearances of Falstaff throughout Burgess’s surveys of the annals of English Literature attests to this enduring popularity. In English Literature: A Survey for Students (1958), Burgess describes Falstaff’s place in the Second Tetralogy as the ‘meat surrounded by dry historical bread.’

Burgess also reproduces the speech that Falstaff gives, disguised as Herne, in The Merry Wives of Windsor (‘The Windsor bell hath struck twelve…’) in his anthology, They Wrote In English: A Survey of British and American Literature, Volume 2 (1979). Here is a recording of him reading the same speech:

Burgess’s own writing is filled with Falstaffian archetypes, men preoccupied with drinking, possessing a love of wit, and a deep interest in the pleasures of the flesh. Traces of Falstaff can be found in the perpetually drunk officer Nabby Adams in Time for a Tiger (1956), the fat Shakespearean actor Willett in The End of the World News: An Entertainment (1982), or even Burgess’s fictional poet and hero of the Enderby novels, F. X. Enderby.

When writers of the Renaissance appear in Burgess’s work, they too are usually characterised with a tinge of Falstaff — WS of Nothing Like the Sun (1964) and Kit Marlowe of A Dead Man in Deptford (1993) are both constantly drinking, poeticising, and altogether very fleshy beings.

In the short story ‘A Meeting in Valladolid’, published in The Devil’s Mode (1989), Burgess imagines a debate between Shakespeare and Cervantes about who was the first to have created the Sancho Panza/Falstaff archetype. This Shakespeare, angry that Cervantes has “stolen a march on him in the domain of universal character”, quickly rewrites Hamlet to produce a performance of The Comedy of Hamlet Prince of Denmark, complete with a happy ending and new additions of Falstaff and Mistress Quickly.

Nowhere is Burgess’s complex and continual engagement with Falstaff and Shakespeare more apparent than in his Sir John Falstaff va alla Guerra, or Sir John Falstaff Goes to War, an unpublished draft script of a play adapted from Shakespeare’s history plays in the Second Tetralogy.

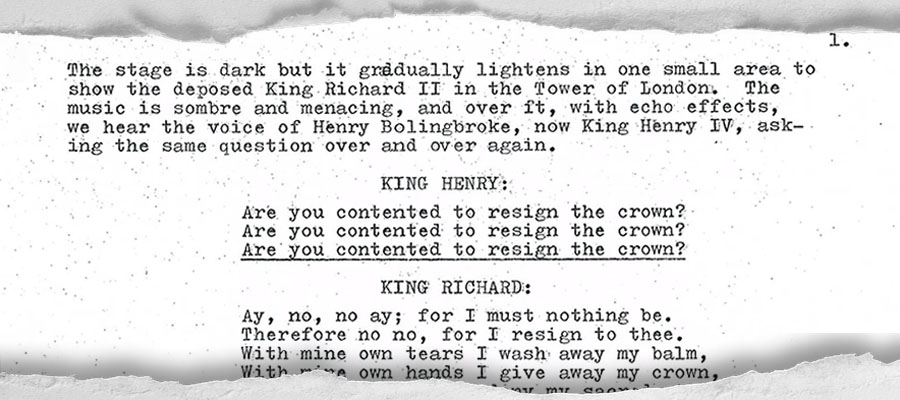

The manuscript held in the Anthony Burgess archive contains a draft of Act One with no clear indication of whether a second act survives or was even written. The extant script is an abridged and refocused adaptation of scenes from Shakespeare’s Richard II and Henry IV, Part 1 with Burgess putting Falstaff’s comedic exploits at the heart of the play.

The play, written at some point during Burgess’s time in Rome during the 1970s, was possibly designed as a vehicle for Burgess’s friend and Italian actor Mario Maranzana, although there is no record of any performances.

Its composition follows Burgess’s time in New York, where he was simultaneously teaching Shakespeare at CCNY and — like Shakespeare — working in the theatre on his stage musical, Cyrano. In his book Falstaff: Give Me Life (1992), Harold Bloom recalls a conversation with Burgess during his stay in New York: Bloom said that Burgess had the skill to imagine Falstaff in conversation, ‘but he demurred’. Yet, later in the same decade, it seems that Burgess composed such a play.

Sir John Falstaff is largely adapted from Shakespeare’s original text, the scenes being linked by Burgess’s invented mock-Shakespearean dialogue and stage directions. While the Falstaff scenes are largely left intact, the historical parts of Shakespeare’s plays have been heavily cut or abridged in Burgess’s much shorter text.

The changes are usually made to contextualise a scene or gloss over the action which surrounds Falstaff’s comedic scenes. For example, the play opens with an expedited version of Richard II’s murder in the Tower to set up the war to which, as Burgess’s title suggests, Falstaff must go.Other changes in Burgess’s adaptation seem to have been made to stage Shakespeare’s sprawling history cycle as a single play. Many lines and speeches are left out. Some minor characters, such as Vernon or Douglas, have their lines redistributed to those who are more central to Burgess’s plot.

He redistributes some of Shakespeare’s lines, to clarify a character’s motivations which have been lost in omitted dialogue. During the murder of King Richard, Burgess adds Exton explaining ‘My hand, King Henry’s will,’ perhaps for the benefit of audiences less familiar with Shakespeare’s histories as well as for the speed and coherence of his own work.

Among these more practical adaptation choices, Burgess includes his own ‘Shakespeare-sounding’ dialogue. Take Hotspur defying King Henry with the rebels, now declaring to oppose ‘this Bolingbroke, / This king with a filched crown. Let honour burn / And Mortimer ascend his rightful crown.’ Smaller additions by Burgess include explanations of perhaps obscure meanings to modern audiences. Take Bardolph’s explanation of the sanguine humour as one that is ‘quick to anger and dangerous,’ or the replacement of ‘Dowlas, filthy dowlas’ with ‘coarse filthy stuff.’

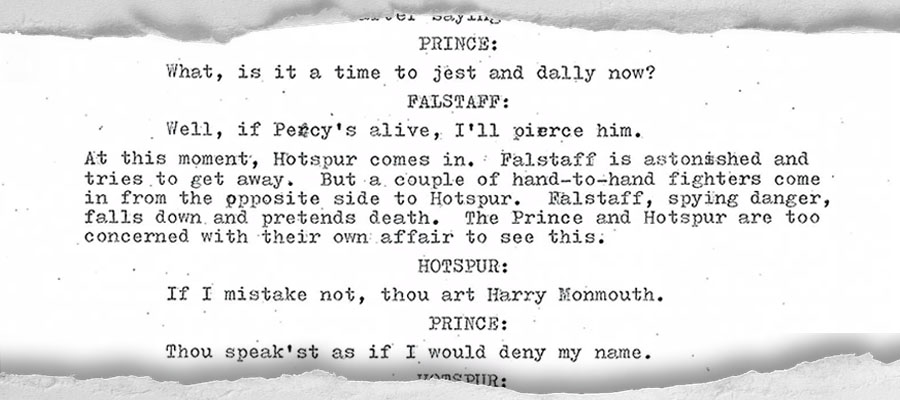

Burgess similarly adds in original stage-directions to link his scenes, frequently reordered or altered in Sir John Falstaff. Falstaff’s discovery sleeping behind the arras turns into his theatrical grand entrance to the scenes in the Boar’s Head Tavern. Falstaff’s cowardice in the battle is fully orchestrated by Burgess during the combat between Prince Hal and Hotspur. He adds this stage direction:

Falstaff is astonished and tries to get away. But a couple of hand-to-hand fighters come in from the opposite side to Hotspur. Falstaff, spying danger, falls down and pretends death. The Prince and Hotspur are too concerned with their own affair to see this.

Yet Burgess’s biggest change is to move the King’s opening speech on the state of the realm in Henry IV, Part 1 after Falstaff’s introduction during the highway robbery. Furthermore, this scene now includes Prince Hal’s ‘son doth imitate the sun’ speech on the motivations behind his riotous behaviour, which is given to the king’s advisor, the Earl of Westmorland.

In doing this, Burgess ensures that his Falstaff play is centred on Falstaff. Prince Hal is not afforded a chance to explain to a sympathetic audience his complexity, nor is King Henry given due prominence. The broader history and psychology of characters within that narrative are secondary to the riot and dishonour in the taverns of London.

The rejection of honour and patriotism, embodied by Falstaff’s self-interest, is made more explicit in Burgess’s play. His cynical attitudes are communicated through added dialogue, with an emphasis on Falstaff’s bribery as head of his division of men.

It is tempting to speculate what the second act of Sir John Falstaff would contain. The implications of Falstaff’s increased stage time in Henry IV, Part 2 would have been ripe for Burgess’s adaptation, and whether Burgess may have stopped here or incorporated his reported death and significant non-presence in King Henry V. The only certainty is that Merry Wives of Windsor, which Burgess did not enjoy as much as the history plays, would not have been included.

Sir John Falstaff shows us something of Burgess’s engagement with what he saw as the essence of Falstaff. It also suggests a desire on his part to emulate and adapt Shakespeare’s original Falstaff for the modern stage, and to show what Shakespeare’s plays might look like if they had less of that ‘dry historical bread’ surrounding the character of the knight.

Burgess’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s original text depicts Falstaff doing what he does because he likes what he does, and the play takes theatrical delight in presenting this.

Let’s finish with Burgess introducing his students at CCNY to Falstaff:

Read Sam Jermy’s other blog post about his research into Burgess and Shakespeare.