The Earthly Powers Bookshelf: St Nicholas

-

Andrew Biswell

- 11th December 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

Anthony Burgess’s Earthly Powers is a book made up of other books. The Earthly Powers Bookshelf charts that literary map, using as its base Burgess’s library at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation.

As the typescript of Earthly Powers approached the end of its decade-long gestation in 1979, there was a significant hole in the book. Burgess knew that Toomey would write an opera libretto at a certain point in the novel, and that this opera would clarify the main theme of the book. But, for a long time, he had no idea what Toomey’s opera would be about.

Towards the end of 1979, Burgess wrote a long synopsis of the novel for his agent, in which he does not specify the subject of the libretto. While publishers in London and New York were reading the synopsis and submitting bids for the right to publish the novel, the problem of the opera remained unresolved.

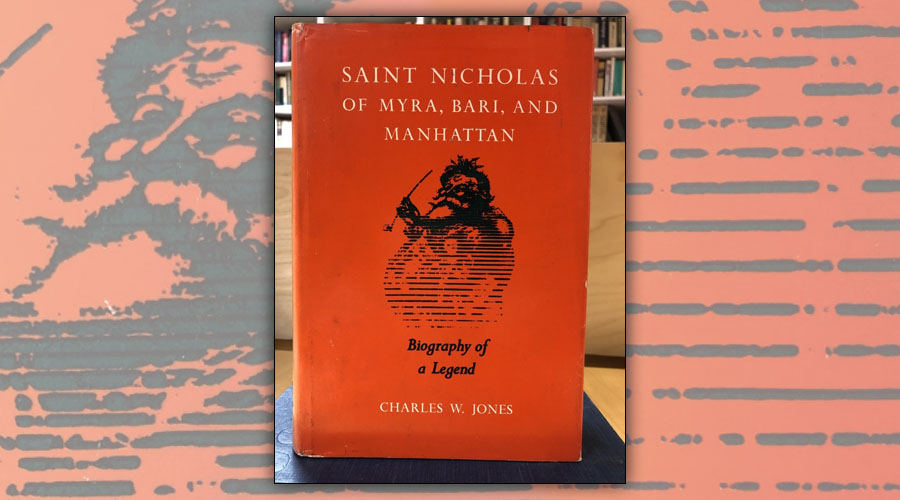

The solution to this dilemma arrived unexpectedly in the post from London. John Gross, the editor of the Times Literary Supplement, sent a book for review. At first glance, the material seemed unpromising: Saint Nicholas of Myra, Bari and Manhattan by Charles W. Jones, published by the University of Chicago Press. As Burgess leafed through the pages and began work on his TLS review, it became clear that the fictional opera had at last found its subject: the life and miracles of St Nicholas.

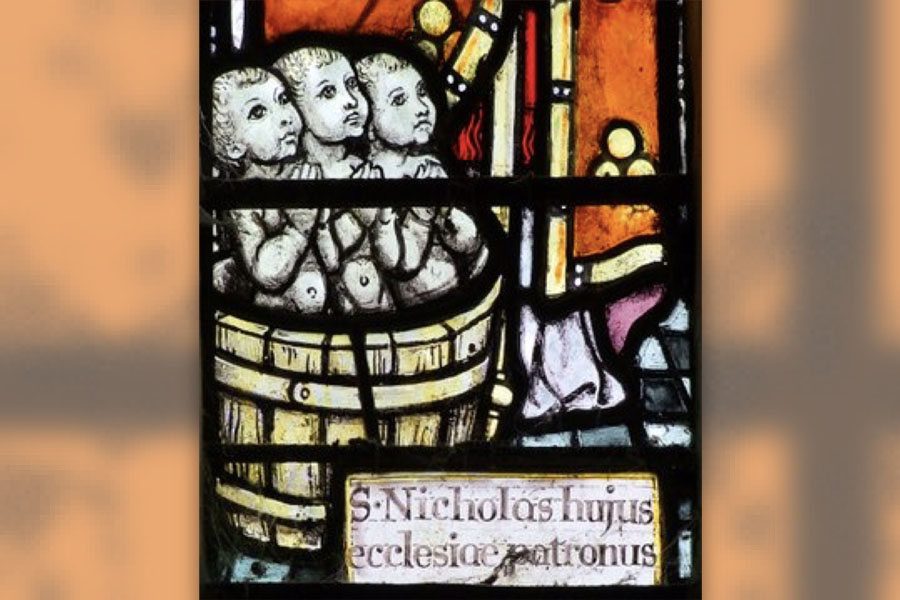

One particular episode in the book caught Burgess’s attention: the legend that St Nicholas brought back to life three boys after they had been murdered and their bodies had been preserved in a pickle barrel, to be consumed by cannibals.

Jones outlines a French story about St Nicholas by Anatole France, in which the three resurrected boys grow up to become great sinners. Nicholas rebukes himself that he has unwittingly brought more evil into the world by performing the miracle which saves the boys, in much the same way that Carlo’s miracle in Earthly Powers has its own terrible consequences. The cannibalism narrative is also replayed towards the end of Burgess’s novel.

We can see how Burgess integrated this material, discovered in the Jones biography, into Earthly Powers. Summarizing his opera in Chapter 61, Toomey says:

At the end the ravaged corpse of a child is brought in. With the child in his arms he [Nicholas] raises his eyes to the invisible God and asks: What is this all about? What’s going on? Why did you let me bring these bastards back to life if you knew what they were going to do? And then the curtain (p. 493).

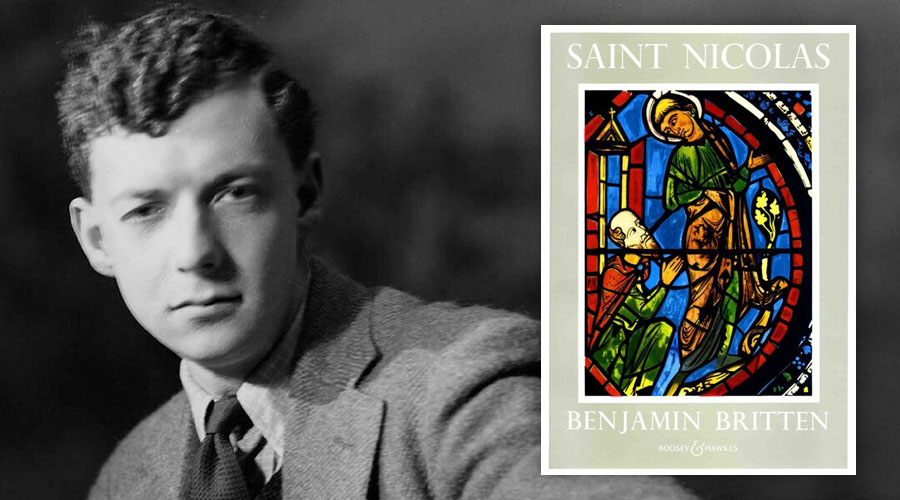

One other influence is worth mentioning. Jones makes a fleeting reference to St Nicolas, the dramatic cantata by Benjamin Britten (1948), but Burgess writes about it in more detail in his TLS review, showing that he knew Britten’s work very closely. Eric Crozier’s libretto for the cantata plays bold games with time, shifting back and forth between various episodes in the life of St Nicolas. As the boy soprano playing the young Nicolas sings ‘GOD BE GLORIFIED,’ the same words are taken up by the tenor who plays the saint as an older man. This episode from the cantata is reversed in Earthly Powers, which begins with Toomey near the end of his life, his earlier story being told in flashback from Chapter 11 onward. This structural mirror-effect between Britten and Burgess may be a coincidence. It’s also possible that Burgess had retained a memory of the time-jumps from the cantata, and tried to emulate them in the ruptured chronology of his novel.

Burgess’s copy of Charles Jones’s book has survived in the library at the Burgess Foundation in Manchester, along with a typescript of his review. Burgess is lively and informal in his examination of the St Nicholas story:

I have just been on the telephone to my Italian translator, Francesca Dragone, who comes from Bari, and she informs me that the cult [of St Nicholas] is as powerful there as it ever was. His bones exude a magical juice, as they always did, he watches over mariners, on his feast day nominal dowries are given to poor but marriageable virgins […] The legend of the pickled boys, which provides a base, though sanctified, thrill for all who listen to Benjamin Britten’s St Nicolas cantata, is the subject both of the earliest known Christian secular drama and of Anatole France’s bitterest irony: in Le Miracle du Grand Saint Nicholas he has the resuscitated three growing up into traitors and villains, with Nicholas doubting the goodness of God.

The publication date of this review reveals how late in the day Burgess added the opera material to Earthly Powers: his article, titled ‘The Santa Claus Story’, appeared in the TLS on 21 December 1979, just a few weeks before he delivered the final manuscript of the novel to Hutchinson in London and Simon & Schuster in New York.

What does Charles Jones’s book tell us about Earthly Powers? Firstly, it demonstrates the extent to which the novel was improvised rather than planned. Even at a late stage in the composition process, Burgess was willing to ride his luck, trusting that something would come along to resolve a plotting dilemma. It also establishes a strong link between his work as a reviewer and his work as a novelist: new books, sent for review, often played a significant role in his fiction-writing process.

St Nicholas helps us to understand Earthly Powers as a novel which is made up of other books. Burgess was a wide and voracious reader: like Autolycus the clown, his favourite character in Shakespeare’s Winter’s Tale, he often described himself as ‘a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles.’ We find further instances of this magpie quality elsewhere in Earthly Powers. For example, when the writer-publisher Harry Crosby shoots himself in New York in Chapter 43, Burgess quotes the poem in memory of Crosby by E.E. Cummings, taken from another non-fiction book (Black Sun by Geoffrey Wolff), which he’d reviewed for the TLS on 14 January 1977. The link between Burgess’s review and Earthly Powers is confirmed by the fact that he deploys exactly the same lines from Cummings which are quoted by Wolff in his life of Crosby.

No doubt further investigation into Burgess’s private library will reveal other volumes which fed into the text of Earthly Powers. Now that the book collection has been fully catalogued, it will be possible for researchers to find out exactly what Burgess was reading, and to establish new connections with the literature he produced afterwards.

Throughout 2020, the Burgess Foundation is celebrating the fortieth anniversary of Earthly Powers, of which this series is a part. Find out more about the Earthly Powers 40 project.