The Earthly Powers Bookshelf: The Poetry of Earthly Powers

-

Graham Foster

- 18th December 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

Anthony Burgess’s Earthly Powers is a book made up of other books. The Earthly Powers Bookshelf charts that literary map, using as its base Burgess’s library at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation.

Poetry is present in Earthly Powers from the earliest scenes in the narrative.

Kenneth Toomey, enjoying his retirement in his grand Maltese palazzo, is invited to dinner at the British Council, where he meets the poet laureate, Dawson Wignall. At first glance, there is nothing too noticeable about Wignall, and he appears to be another fictional character, created wholly by Burgess. Yet it becomes apparent that Burgess is caricaturing John Betjeman, who was poet laureate between 1972 and 1984.

Wignall’s poetry is described at the beginning of Chapter 4 as being ‘derived from Anglican Church services, the Christmas parties of his childhood, his public-school pubescence, suburban shopping streets; he occasionally exhibited perverse velleities of a fetichistic [sic]order, though his drooling over girl’s bicycles and gym tunics and black woollen stockings were chilled by whimsical ingenuities of diction’. In this brief critique of ‘Wignall’s’ work are references to Betjeman poems such as ‘Indoor Games Near Newbury’, in which the poet recalls the events of a children’s party, ‘Christmas’, in which the poet interrogates the nativity, and even the notorious couplet ‘Sometimes I think that I should like, / To be the saddle on a bike.’

Any doubt as to the parody is removed completely as Burgess gives an example of one of Wignall’s poems, replete with references to church, children’s parties and burgeoning sexuality:

Thus kneeling at the altar rail,

We ate the Word’s white peppery wafer.

Here, so I though, desire must fall,

My chastity be never safer.

But then I saw your tongue protrude,

To catch the wisp of angel’s food.

Dear God! I reeled beneath the shock:

My Eton suit, your party frock,

Christmas, the dark, and postman’s knock.

This is an overt parody of Betjeman’s style, but there are also several overt references to his poetry. Again, the poem ‘Indoor Games Near Newbury’ appears the be one of the inspirations for this parody, in particular the reference the a ‘party frock’ and the idea of a pubescent sexual awakening at a party. Yet, Burgess’s Betjeman-esque poetry is more hyperbolic that its model ever was.

Writing in the London Review of Books, John Bayley analyses the poem in Earthly Powers: ‘In a brilliant piece of word play the angel food cake of the children’s tea party becomes the Host: sex, worship and childhood come together on the tip of the darting tongue that demurely holds it. Essence of Betjeman, it would seem, compressed into a few workmanlike lines. But not so. Betjeman himself is never so explicit in his real poetry. It escapes, in fact, from its always apparently so intrusive subject-matter.’

It is not immediately apparent as to why Burgess presented such an uncharitable caricature of Betjeman in Earthly Powers: perhaps to reinforce Toomey’s sharpness when it comes to his peers, or perhaps an element of jealousy that Betjeman was richly rewarded by the establishment for his literary work, when Burgess wasn’t. For the reader, it is a fun, winking joke, but it is not the only engagement with poetry in Earthly Powers.

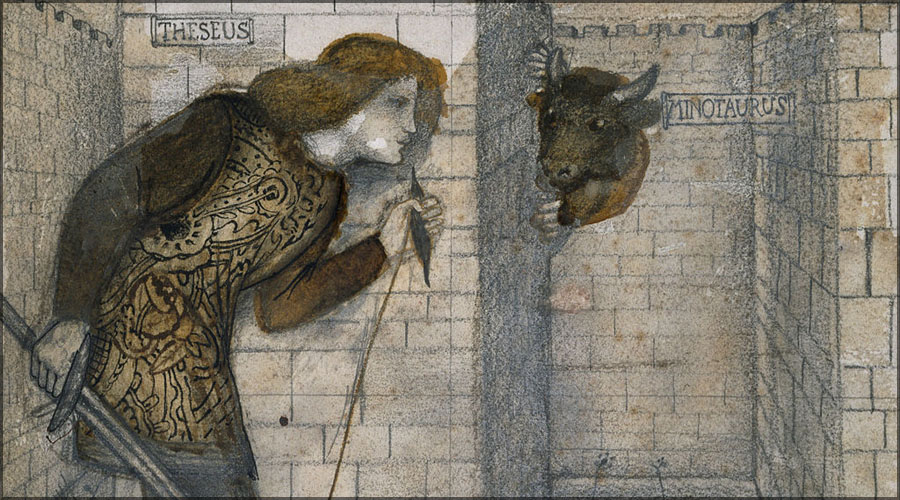

Burgess learned about poetry primarily through the work of modernists such as T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, and both these writers are referenced in various ways in Earthly Powers. What are more surprising are Burgess’s references to classical poetry. Throughout the novel, the refrain ‘solitam… Minotauro… pro caris corpus’ appears, in the mumbled sleep-speech of Toomey’s secretary Geoffrey, in the fragment of The Way Back to Eden, Toomey’s unpublished novel, and on a piece of paper at the concentration camp Toomey visits after the war. These words are from Catullus 64:

Cecropiam solitam esse dapem dare Minotauro.

Quis angusta malis cum moenia vexarentur,

Ipse suum Theseus pro caris corpus Athenis

Proicere optavit potius quam talia Cretam

Fubera Cecropiae nec funera portarentur;

Catullus’s poem deals with the story of Theseus and Ariadne, who enter the labyrinth of Knossos and kill the Minotaur at its centre. These lines deal with the maidens who were fed to the Minotaur as a sacrifice, and Theseus offering up his own body for Athens to prevent more funerals of these maidens. The poem itself is labyrinthine and may give a hint at how to read Toomey’s plight in Earthly Powers. Toomey enters into the labyrinth of the twentieth century, his spiritual battle with Carlo Campanati mirroring Theseus’s battle with the Minotaur. Catullus laments the loss of a time ‘before religion was despised’, before the sins of man brought those days to an end, and Burgess uses Catullus’s words alongside images of degradation.

This shows that Burgess has chosen his poetic influences in Earthly Powers carefully, though for various reasons. His writing about Dawson Wignall is a flourish of humour that sets up Toomey in conflict with his peers, whereas his use of poets such as Catullus helps him to create a mythic structure to his novel.

Pictures above: John Betjeman (Daily Herald Archive); Theseus and the Minotaur in the Labyrinth, 1861 (Edward Burne-Jones)

Throughout 2020, the Burgess Foundation is celebrating the fortieth anniversary of Earthly Powers, of which this series is a part. Find out more about the Earthly Powers 40 project.