The Clockwork Collection: Utopia, Dystopia, Walden Two

-

Andrew Biswell

- 23rd February 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

-

tagged as

- 1985

- A Clockwork Orange

- Aldous Huxley

- Beyond Freedom and Dignity

- Brave New World Revisited

- dystopia

- Enderby

- George Orwell

- Ludovico Technique

- Rex Warner

- Samuel Butler

- Skinner

- Stanley Kubrick

- The Clockwork Collection

- The Clockwork Testament

- The Complete Enderby

- The Novel Now

- The Wanting Seed

- Thomas More

- utopia

- Walden Two

- William Morris

2021 marks the 50th anniversary of the first release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange and 60 years since Anthony Burgess completed his most famous novel.

To celebrate the anniversary, we present an online series called The Clockwork Collection, with a focus on A Clockwork Orange.

Each month, we’ll be sharing a highlight from the Burgess Foundation’s archive. Expect literary manuscripts, vinyl, books, audio, journalism, music scores, photographs and more. For more information on the items discussed in the series, please contact our archivist.

The Clockwork Collection: Utopia, Dystopia and Walden Two

Among other things, A Clockwork Orange is the product of Burgess’s wide reading in the history of literary utopias and dystopias. In his non-fiction book The Novel Now (1967), he devotes a chapter to the books which informed his own dystopian novels, such as The Wanting Seed and 1985.

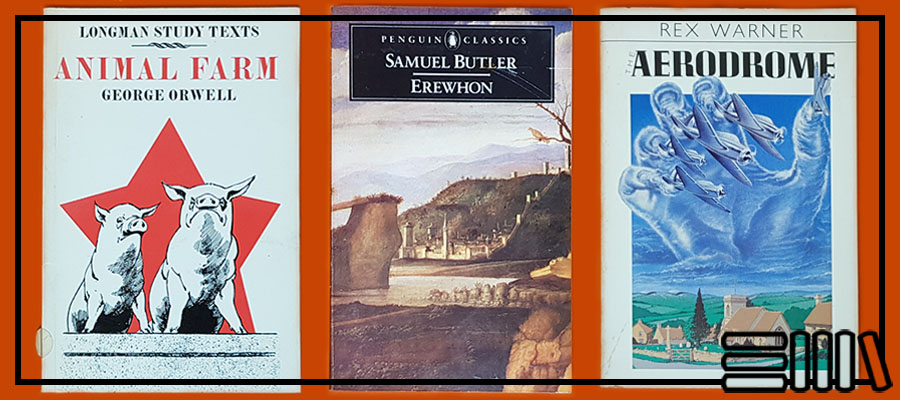

The reading room and archive at the Burgess Foundation contain more than 9000 volumes from the personal libraries of Anthony Burgess and his two wives, Lynne and Liana. Within the book catalogue we find a large number of utopian and dystopian titles, including Animal Farm by George Orwell, Erewhon by Samuel Butler, News from Nowhere by William Morris, and multiple copies of The Aerodrome by Rex Warner.

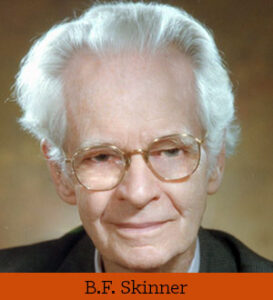

One of the most significant utopian works in the Foundation’s collection is Walden Two by the Harvard psychologist Burrhus Frederic Skinner, who was one of the pioneers of behaviourism. Skinner’s novel, published in 1948, is a utopian manifesto in the polemical tradition of Thomas More and William Morris.

Although it takes the form of a novel, Walden Two is a bold attempt to describe what an ideal society might be. Within the frame of fiction, the protagonists are guided around the Walden Two experimental community by one of its leaders, a character called Frazier, who is a self-projection of Skinner.

Attempting to create a better society, a group of men and women have opted out of the modern world and set up a commune where there is no crime and everyone can be happy. There is no class system, fashion, advertising or alcohol in this utopia. Members of the community work only four hours a day, and money has been replaced by ‘labor-credits’.

Attempting to create a better society, a group of men and women have opted out of the modern world and set up a commune where there is no crime and everyone can be happy. There is no class system, fashion, advertising or alcohol in this utopia. Members of the community work only four hours a day, and money has been replaced by ‘labor-credits’.

Burgess was horrified by what he found in the pages of Skinner’s utopia. He had first encountered behaviourism in the late 1950s, while he was reading widely and preparing to write A Clockwork Orange. One of the works he consulted was Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World Revisited. Huxley’s book provided a summary of Science and Human Behavior (1953), the non-fiction book in which Skinner developed his theory that there is no such thing as human nature, and that environment determines everything. To Burgess, who believed in the primacy of free will and individual choice, these ideas were objectionable. One of his aims in A Clockwork Orange was to set out the counter-argument in favour of free will.

Another book by Skinner, provocatively titled Beyond Freedom and Dignity, appeared in 1971, a few months before the release of Stanley Kubrick’s film version of A Clockwork Orange. This was Skinner’s attempt to popularise his theories in a short book aimed at the mass market. Declaring himself to be against ‘the literature of freedom’, he wrote that the next step in social evolution was ‘not to free men from control but to analyze and change the kinds of control to which they are exposed.’

Given the right environment and a willingness to abandon traditional notions of freedom, Skinner claims, utopia might become a reality for everyone.

The thematic connection with A Clockwork Orange was obvious to many readers of Beyond Freedom and Dignity. Interviewed by Rolling Stone magazine, Kubrick said: ‘I like to believe that Skinner is wrong and that what is sinister is that this philosophy may serve as the basis for some kind of scientifically oriented repressive government.’ He added: ‘I like to believe that there are certain aspects of the human personality which are essentially unique and mysterious.’

Burgess attacked Skinner’s ideas in three notable works of the 1970s. The first of these was a short story, ‘A Fable for Social Scientists’, published in Horizon magazine in 1973. Set in the future, the story is a dialogue between three students who accidentally discover Skinner’s burial site. They talk dismissively about Walden Two and Beyond Freedom and Dignity before speculating about the possible meaning of the initials ‘B.F.’ (‘Bloody Fool’ seems to be Burgess’s preferred answer). Echoing the central message of A Clockwork Orange, one of the characters says: ‘Freedom only matters in this area of choosing between good and evil, and that comes down, I suppose, to choosing not to do evil.’

The next encounter with Skinner may be found in The Clockwork Testament, published in 1974 (illustrations pictured below). This novel features a fiery confrontation in a television studio between the poet F.X. Enderby and an academic psychologist called Professor Balaglas, who closely resembles Professor Skinner. Burgess is unsparing in his criticism of Skinner for rejecting ideas such as free will and the autonomous individual who is not conditioned by their environment. Balaglas, speaking the language of Skinner, says: ‘Man is much more than a dog, but like a dog he is within range of a scientific analysis.’ To which Enderby replies: ‘Man was always violent and always sinful and always will be. He won’t change, not unless he becomes something else.’

Burgess resumed the attack on Skinner in his hybrid book 1985, half novella and half critical work about Orwell’s dystopia. In the critical section Burgess writes: ‘We hear less of Pavlovianism these days than of Skinnerism […] To consider hypnopaedia, or sleep-teaching, cradle conditioning, adolescent reflex bending, and the rest of the behavioural armoury, is to be appalled at the loss of individual liberty.’ On this occasion the target of his criticism was not Walden Two but Beyond Freedom and Dignity.

In fairness to Skinner, it’s worth pointing out that his preferred methods of social control bear no resemblance to the Ludovico treatment given to Alex in A Clockwork Orange. ‘Positive reinforcement’ was at the heart of Skinner’s experimental methods, and he was never an advocate of aversion therapy. While Burgess and Skinner disagreed on the questions of free will and the primacy of the individual, there is a strong element of caricature in Burgess’s representation of Skinner’s thinking, which was fundamentally optimistic and utopian. A careful reading of Walden Two and his non-fiction works reveals more complexities than Burgess was sometimes willing to acknowledge.

Thanks to a new collaboration with JISC Library Hub, it is now possible to search the complete list of English-language book titles in the Burgess Foundation’s collection.

Further research into the book collection will allow us to investigate the sources of Burgess’s writing in more detail, and to establish new connections between the books on his shelves and the works which emerged from his typewriter.