Burgess and American Literature: Part One

-

Graham Foster

- 8th March 2013

-

category

- Blog Posts

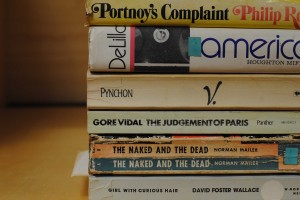

Anthony Burgess’s engagement with American fiction, and indeed American culture in general, is well documented. The collection of Burgess’s book in the reading room at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation contains novels by Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal, Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon and even younger writers such as David Foster Wallace and the Canadian novelist Douglas Coupland. There are also biographies of authors such as F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Steinbeck, Raymond Chandler and James Jones (whose biography carries a recommendation by Burgess on the dust jacket (‘impossible to put down’) even though he had written in The Novel Now (1971), that ‘the trouble with Jones’s writing is that it totally lacks distinction’).

Burgess moved to New York in 1972 to take up a year-long teaching position at City College. One of his colleagues in New York was the novelist Joseph Heller, whose novel Catch-22 Burgess had reviewed in 1962. The review itself has some reservations about what he sees as a ‘sickeningly’ sentimental subtext about ‘ordinary men being decent whatever their nation’. He writes, ‘The thesis of “Catch-22” (a brilliantly contrived book) can only be universal when the whole world has been absorbed into the American empire”. Later, in Ninety-Nine Novels, perhaps inspired by his meeting with Heller, Burgess revises his opinion, stating that ‘the mythopoetic power of Heller’s novel is considerable’.

Burgess’s general view of the fiction of his American contemporaries is one of cautious enthusiasm. For example, in his 1978 review of Don DeLillo’s Running Dog, a novel about the search for a pornographic film featuring Hitler, Burgess writes, ‘in much contemporary American fiction, we have no humanity at all – bodies, nerves, trigger-fingers, money-lust, power-lust, but no (ah, ridiculous Dostoevskian archaism) soul’. He then goes on to enthuse about DeLillo’s voice as ‘harsh, eroded, disturbingly eloquent’.

Here, Burgess’s comments prefigure those of later American writers who, in the 1990s, began to be anxious about postmodern depictions of inhumanity. Perhaps the author that most clearly articulated a desired move away from preoccupations of Burgess’s American contemporaries was David Foster Wallace, who believed that good fiction was about what it means to be a human being. This was a reaction against the high postmodern writers that Burgess was reading and reviewing. Wallace even echoes Burgess’s writing on the lack of Dostoevskian soul in his essay ‘Joseph Frank’s Dostoevsky’:

‘Who is to blame for the unseriousness of our serious fiction? The culture, the laughers? But they wouldn’t (could not) laugh if a piece of morally passionate, passionately moral fiction was also ingenious and radiantly human fiction. But how to make it that? How – for a writer today, even a talented writer today – to even get up the guts to try?’

In 1978, Burgess’s words are similar as he tries to diagnose the problems of American literature from a European perspective:

‘Perhaps this reduction of fictional characters into thinghood began with Hemingway. Hemingway, like Lawrence, rejected the cerebrum and concentrated on the cerebellum, replacing 19th-century liberal man with natural man – man as a gun-using, lusting, unloving instrument with, however, a kind of antiquated pilot-flame called honor flickering faintly. Faceless and heartless, post-Hemingway unnatural man is an urban cipher, prey to totally inhuman predators that have acronyms for names. If there is a ghost anywhere in the machine, it is a fist-sized ganglion of fear sometimes masquerading as guilt.’

Burgess’s American contemporaries were also quick to critique his own fiction. Gore Vidal, in his essay ‘Why I am Eight Years Younger That Anthony Burgess’, remembers his first meeting with Burgess as one of stilted communication: ‘I had been drinking, but not that much, while the tall man appeared sober. Obviously, I was having my chronic problem with English voices’. But Vidal was impressed by Burgess’s reviewing of his own book in the Yorkshire Post (‘I was delighted: Whitman had done the same’) and the two became friends. Vidal believed Burgess was ‘wise enough to allow his obsessions with religion, sex, language, to work themselves out as comedy’. In turn, Burgess described Vidal as ‘one of the most inventive novelists modern America has produced’.

But Burgess’s interactions with American writers were not always so genteel, or mutually congratulatory. In an article for the Los Angeles Review of Books, Jonathan Lethem remembers meeting Burgess at a reading in 1985. Lethem, a fan of Burgess’s work with first editions to be signed, asked whether The Wanting Seed (Lethem’s favourite) was inspired by Philip K. Dick. Unimpressed, Burgess replied that he didn’t read science fiction. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that Burgess read widely within the science fiction genre, praising authors such as Ray Bradbury, H.G. Wells, Robert Silverberg and Brian Aldiss.

Another notable exchange with an American writer happened in 1973. Commissioned to write a piece for Rolling Stone, Burgess struggled with his assignment, eventually sending a letter from Rome explaining that ‘things are hell here’. He writes, ‘I have a 50,000-word novella I’ve just finished, all about the condition humaine etc. Perhaps some of that would be better than a mere thinkpiece’. Unfortunately, this letter was to find its way to the desk of Hunter S. Thompson, who replied with some fury:

‘What kind of lame, half mad bullshit are you trying to pull over on us? When Rolling Stone asks for a “thinkpiece,” goddamnit, we want a fucking thinkpiece… and don’t try to weasel out of it with any of your limey bullshit about a “50,000 word novella about the condition humaine, etc…”’

The desired thinkpiece never appeared in the pages of Rolling Stone, but the essay referred to in these letters, ‘The Clockwork Condition’, was eventually published in the New Yorker in 2012.