Burgess, Earthly Powers and the Papacy

-

Will Carr

- 3rd April 2020

-

category

- Earthly Powers 40

-

tagged as

- Catholicism

- Earthly Powers

- Earthly Powers 40

- scots

As part of our project marking the 40th anniversary of Earthly Powers this year, we present a series of blog posts exploring different aspects of Burgess’s monumental work.

‘The novel is about the difficulty of deciding what is good and what is evil.

‘The narrator is modelled on William Somerset Maugham. His sister married an Italian musician whose brother was a priest. The priest, Carlo Campanati, rose to be Cardinal Archbishop of Milan and evenutally, in 1958, Pope Gregory XVII. He can, if the reader wishes, be identified with Pope John XXIII.

‘The writer narrator is asked by the Vatican to confirm that he witnessed a miracle performed by Pope Gregory, when he was still only Monsignor Campanati, in a Chicago hospital in 1929. The narrator, whose fictional trade leads him to confuse the imagined with the actual, is forced to look back over his long life, assemble the undoubted historical and biographical and separate them from what is fabled by the daughters of memory.

‘He sees the miracle clearly: a small boy dying of meningitis is restored to life by the laying on of hands and a simple prayer. But what happened to this boy in later life? Surely God had some special intention for him?’

Anthony Burgess, writing prior to the publication of Earthy Powers for the Scotsman, sets up his epic narrative – at the heart of which is the figure of his fictional pope, Gregory XVII. Burgess wrote a number of articles about various popes, in which he tends to take a wry, somewhat ironic tone befitting a Catholic renegade. For example, here he is reviewing The Year Of Three Popes by Peter Hebblethwaite in 1979:

‘Employed last year [1978] by Il Giornale Nuovo of Milan to deliver ruminations on the Papal elections, I made all the wrong predictions and was even threatened with anathema for suggesting, in the light of new scientific examinations of the Turin Shroud, that the job of the new Pope might well be to reframe the doctrine of Christ’s resurrection. I said all the peccable things in fairly impeccable Italian, which made matters worse…’

The papal upheaval in the Vatican in 1978 was matched in 2013 with the surprise resignation of Benedict XVI and the elevation of Francis, the first Jesuit to become Pope: we can be fairly confident that Burgess would not have successfully predicted that, but he may have had opinions about it.

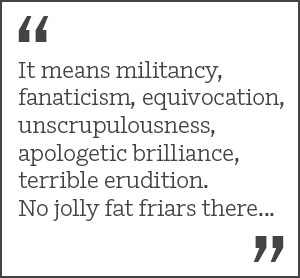

Anthony Burgess had strong views on Jesuits, writing in 1980 (in a review of Jesuits: A History by David Mitchell) that ‘If the Catholic Church ever seems dangerous to the children of reform, it is invariably because the Jesuits are grimly at work. Jesuitry, in the English lexis, carries no amiable connotations. It means militancy, fanaticism, equivocation, unscrupulousness, apologetic brilliance, terrible erudition. No jolly fat friars there: lean men rather with blue jaws who curiously reconcile the ascetic and the worldly, men who will stop at nothing.’

Anthony Burgess had strong views on Jesuits, writing in 1980 (in a review of Jesuits: A History by David Mitchell) that ‘If the Catholic Church ever seems dangerous to the children of reform, it is invariably because the Jesuits are grimly at work. Jesuitry, in the English lexis, carries no amiable connotations. It means militancy, fanaticism, equivocation, unscrupulousness, apologetic brilliance, terrible erudition. No jolly fat friars there: lean men rather with blue jaws who curiously reconcile the ascetic and the worldly, men who will stop at nothing.’

In Earthly Powers, Burgess’s fictional Pope has some of these qualities. Carlo Campanati, later Gregory XVII, is ruthless, brilliant and erudite; however, he is also extremely fat, charismatic, and not a little diabolical. As he outlines, Burgess identifies the character strongly with Pope John XXIII, the architect of the Second Vatican Council, which had various modernising effects including encouraging ecumenical dialogue and vernacularizing the Latin Mass.

In Burgess’s opinion, John XXIII was ‘an emissary of the Devil’ and ‘a Pelagian heretic’. As he says in his essay ‘On Being a Lapsed Catholic’ (1967): ‘I find that I have no quarrel with the whole corpus of Catholic doctrine; granted the ignition spark of faith, all the tenets of the Church would hold for me. Indeed, I tend to be puristic about these, even uneasy about what I consider to be dangerous tendencies to slackness, cheapness, ecumenical dilutions.’

Without the spark of faith, even at the end of his life Burgess could not countenance returning to a church that he no longer recognised: his stated wish was that there should be no religious observance at his funeral.

After the publication of Earthly Powers, Burgess continued to write about popes, covering the visit of John Paul II to England in 1982, and reviewing that pope’s plays for the Times Literary Supplement in 1988 as well as John Cornwell’s investigation into the sudden death of John Paul I, A Thief in the Night, for the Observer in 1989. Despite his lack of faith, he nonetheless saw the figure of the pope as being very important in terms of spiritual and moral leadership.

Perhaps Burgess summed up what he thought real-life popes should do best in his 1982 article, ‘The Papal Bandwagon’:

‘If the Pope’s sacred function spills over into the secular world it must be through reiteration of the fundamental truth that men and women are free to make moral choices. There seems to be nobody else in the world today who has that basic authority.’