Inside the archive: volunteering at the Burgess Foundation (part 2)

-

Vivian Pencz

- 19th March 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

In the second blog post from our archive volunteers, Vivian Pencz shares her experience of working with one of Anthony Burgess’s unpublished notebooks as part of a remote transcription project.

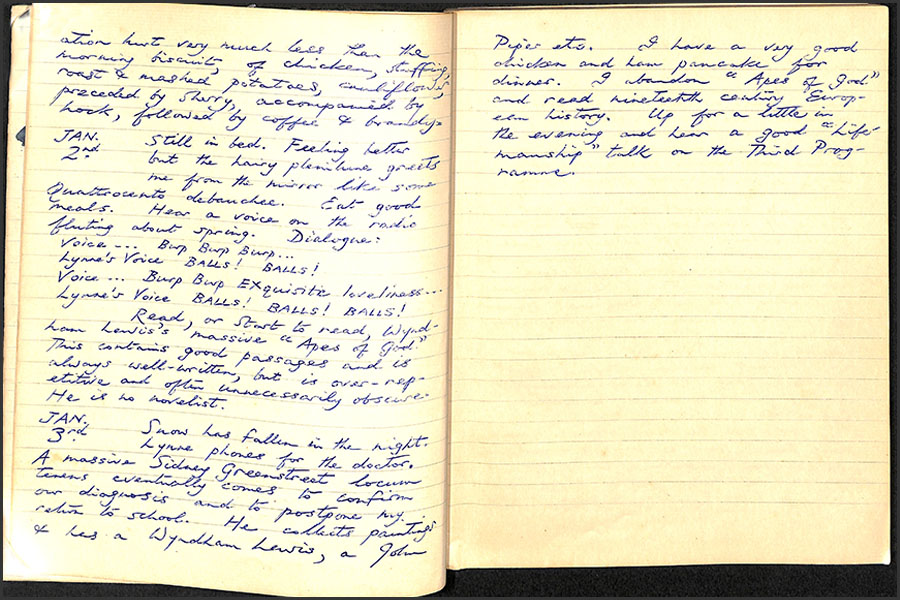

‘Journal of the Plague Year 1951,’ declared the title of the first Burgess notebook I transcribed as a new Archive Volunteer for the Foundation. Meanwhile, its last page — flipped upside-down and used as a second starting point for the diarist, so that you can read the notebook from both ends — bore another ominous title: ‘Down with Big Brother.’

In the year of our plague 2020, and increased mass surveillance, this certainly felt like some kind of fate. ‘Now all the world is but a hospital,’ Burgess later quotes in one of his entries, another eerie coincidence which I experienced while examining the notebook during this pandemic. But these oddly fitting references weren’t what originally drew me to work with this journal for my primary archival project, supervised by the Foundation’s dedicated and supportive archivist, Anna Edwards.

It intrigued me as the sole notebook of 14 in the Archive’s collection that was shared between Burgess and his first wife Lynne, born Llewela Jones. I’d always wanted to know more about Lynne as her own person, rather than the alcoholic ex-wife or reduced muse whose wartime trauma helped to inspire A Clockwork Orange. I felt this way especially because Burgess himself tended to belittle Lynne’s many accomplishments.

The notebook’s joint entries, some of the collection’s most personal accounts, are a vivid window into the couple’s enmeshment. Lynne sometimes takes over sentences that Burgess has abandoned midway, each of them getting bored of the process in turns.

Lynne once goes as far as to edit what her husband’s written, making unsolicited corrections and even passive-aggressive digs, not seeming to care if he reads them (in fact, maybe hoping he would). For example, ‘I can’t help feeling that a minor affair apiece might do us both a bit of good.’

Still, there are glimpses of tenderness within, like when Lynne falls victim to the 1951 flu epidemic. Says Burgess, ‘This journal begins to justify its title too early and ironically.’ He writes about holding Lynne throughout the night, trying to keep her warm, which ‘develops in [him] dreams of a painful erotism.’

Needless to say, when I first started working in the Foundation’s café-bar three years ago, I never expected to become this intimately acquainted with Burgess and Lynne’s inner world.

Sickness features throughout the notebook, Burgess grumbling of constipation like his future alter ego Enderby, while the perpetually hungover Lynne goes to hospital when she’s bitten by a potentially rabid monkey. I should mention now that this notebook is an important and colourful record of the pair’s pre-fame life, including Burgess’s early teaching career in Banbury and, later, in Kuala Kangsar. The monkey incident occurs in Malaya.

The Malayan entries are the most exciting and complex in the journal, which required meticulous research into the couple’s life abroad. Burgess peppers the notebook with infinite cultural references, from H.G. Wells to Walter Hilton. Once abroad, Burgess begins to mix in depictions of south-east Asian cuisine, wildlife, and language too, which made the task of writing an equally infinite list of endnotes demanding but fascinating.

In the first Malaya-based entry, it took me a while to identify creatures called ‘chuck chuck-ing chichaks’, a local colloquialism for the house lizard, as well as the Haywood Estate murder in Sungai Siput that Lynne complains of a couple weeks later. I eventually deduced that the murder was probably an event within the Malayan Emergency, a guerrilla war fought in the Federation of Malaya from 1948 to 1960. That led me to wonder if this hostile atmosphere contributed to Lynne’s palpable unhappiness with her new home.

I was challenged again by enigmatic mentions of a ‘Malayan Symphony’ Burgess had just composed and a new novel that he’d begun, ‘Love from Olympus’, in 1956. With help from Andrew Biswell, Anna and I gathered that ‘Love from Olympus’ was Burgess’s early working title for The Eve of St Venus.

Later, upon reading an excerpt from This Man and Music by Burgess, the ‘Malayan Symphony’ mystery was somewhat solved. While I now had a full description of the composition, I was disappointed to learn that the score was never performed and lost to time.

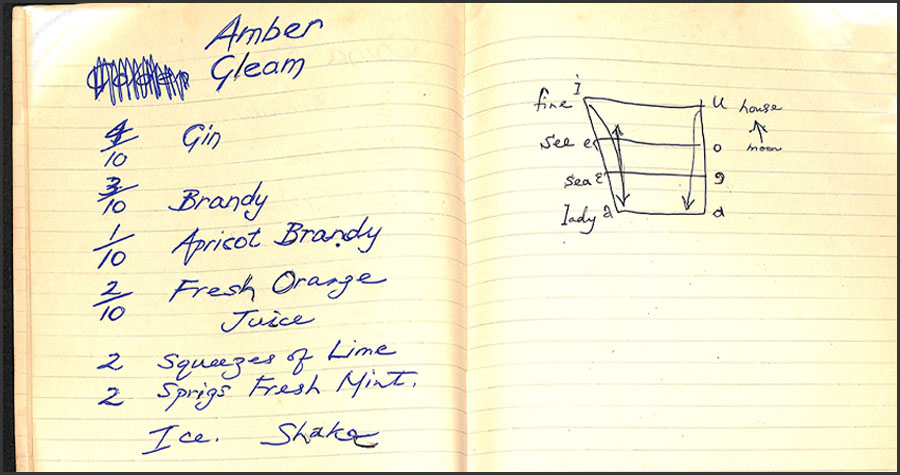

Another difficulty popped up in the form of an unexplained diagram, surrounded by a series of seemingly unconnected words, which no one at the Foundation could decipher. At first, I thought it had something to do with mixology since the diagram had been drawn alongside Burgess’s homemade cocktail recipes. Given names like ‘Late Monsoon’ and ‘Singing Bamboo’, I’d tasted a few of these at the Foundation’s ‘Time for a Tanqueray’ event in 2019, where Burgess’s cocktails were served.

In any case, a French-Mancunian friend of mine cracked the riddle diagram, when she recognised it from her English studies as a vowel pronunciation diagram — unfortunately undrinkable.

As a writer and artist with a journalistic background, I’ve always been interested in cultural history and subversive figures like Burgess and Lynne. Although Lynne spends much of this notebook fussing over domestic burdens, I’ve discovered that she was as unafraid of expressing herself or arguing with politicians as she was of exotic animals and drinking champagne at 10am.

I’m looking forward to discovering more pieces of Mancunian heritage with the Archive and helping bring them to light.