Burgess, Keats and Romanticism

This is my first blog post for the Burgess Foundation where I have started as an AHRC-funded Cultural Engagement Fellow for a three-month placement working on Anthony Burgess, John Keats and Rome. This is a postdoctoral position, my PhD having been written on the work of the contemporary poet Michael Symmons Roberts. It is perhaps unsurprising that given my interest in studying and writing poetry, that my attention was drawn to one of Burgess’s own poetical engagements. What makes this project particularly fascinating for me is the way in which the resources at the Burgess Foundation offer such an extensive opportunity to observe in detail the creative process of a writer of Burgess’s reputation.

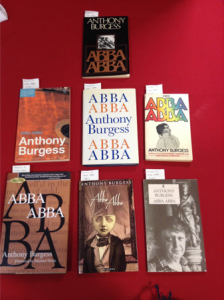

In 1977, Anthony Burgess published Abba Abba, a fictionalised account of the last days of the poet John Keats and a speculative meeting that took place between Keats and poet of the Roman vernacular Giuseppe Gioachino Belli. The first part of the book contains the narrative of this meeting. The second part consists of seventy-odd translations of Belli’s sonnets, which are irreverently and scatalogically irreligious in both content and language. Over the next three months, my research project will centre around this book. I will be considering the broad range of materials the Burgess Foundation has in relation to the book (Burgess’s notebooks, annotated books, letters, films) as well as trying to source new materials from other archives.

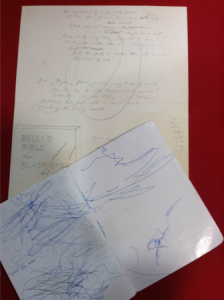

My first week has been spent in the archives and getting used to these new materials. It has been a real pleasure to be able to enjoy the marginalia that accompany the objects. These include for instance the receipts, serviettes, sheets of cigarette packet foil and ticket stubs that Burgess used to bookmark the enormous volumes that comprise Belli’s thousands of sonnets.

Burgessian bookmarks

It also includes an angry, circular scribble through one of his poems I mistook for a fit of a creative temper, which however turned out possibly to be an ‘improvement’ made by Burgess’s then young son Andrea. The fact that his child had access to a yellow notebook, in which the poems are still in a largely inchoate form (lists of rhyming words, partial sentences, more crossed out than not), recommended Burgess to me in a way that I had not expected. I am also decidedly not precious about by own notebooks and they have been similarly ‘improved’ by my two-year old daughter, as one can see in the photo below:

Improvements

The creative process by which Burgess arrived at his translations of Belli’s sonnets may well prove to be a particular focus of this project. Extensive work has already been done on this subject by Paul Howard. Howard closely studies the relation between Burgess’s published sonnets and the prose translation made for him from the Romanesco by Susan Roberts. A legal pad filled with Roberts’s translations is here at the Foundation. However, some new material, most significantly the yellow notebook containing Burgess’s first versifications of the translations had not yet come to light at the time of Howard’s writing. There are also audio recordings Burgess made at home of himself reading the poems, which seem to have formed part of his editorial process. Altogether, these sources should allow me to create a fairly detailed reconstruction of at least one or two of the translations formational journeys towards publication.

Abba Abba covers at the archive

The central focus to begin with will be on Keats or to be more specific Burgess’s Keats. A.S. Byatt describes how in the case of Burgess’s Keats the reader has ‘the grim voice of the dying surgeon speak[ing] in counterpoint to the classical, flowery poet’ (Abba Abba, p. 4). Others have noted too how Burgess’s fictional biography of Keats (in a similar way to his account of the life of Shakespeare) challenges any notions of Keatsian purity. Burgess does this largely through a de-sanitising of the Keats-myth in both content, language and emotion. The process of de-sanitisation can be seen for instance in passages such as the following, in which Keats tirades against his friend Severn for withholding the laudanum from him that he wants to use to commit suicide: ‘Oh, damn and bugger your civil code and your cold Christ Severn. I want no more of this. Dying in bloody cack and sweat and shivers.’ (Abba Abba, p. 57).

Burgess’s own engagement with Keats extends to his anthology of English literature Scrissero in Inglese (They Wrote in English), published in Italy in 1979. This is accompanied by recordings of Burgess reading Keats. In fact in another recording of Burgess’s reading Keats, this time on the Spanish Steps in Rome in front of the house in which Keats died, Burgess foreshadows the conflicted and infuriated Keats that would eventually emerge on the pages of his novel. Burgess writes in the second volume of his autobiography that while ‘reciting the odes, I became aware of a kind of astral wind, a malevolent chill, of a soul chained to the place where the body died, of a silent malignant laughter that mocked not my reading but the poems themselves’ (You’ve Had Your Time, p. 327-328).

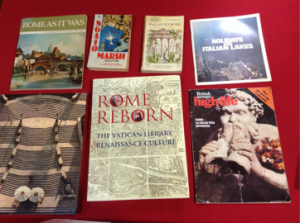

A final and broader line of inquiry is around the city of Rome itself. Rome functions as the setting against which Burgess’s invented meeting between Keats and Belli takes place (the meeting was entirely possible in terms of dates, but there is no historical corroboration—the possibility alone is enough of an opportunity for Burgess to seize on). While Abba Abba was completed in Monaco, the book published in 1977 and Beard’s Roman Women published the year before are directly influenced by the fact that for some time Burgess lived in Bracciano on the outskirts of Rome and also kept a flat in the city. Beard’s Roman Women contains a series of photos of Rome in reflective surfaces by the photographer David Robinson, which Burgess appreciated for the way they portrayed ‘Rome under the rain’ stripped of its typically is sun-soaked glamour. (You’ve Had Your Time, p. 318).

Rome does not always get the best press in Burgess’s writing. In the book 1985, half-literary criticism half-dystopian novella published in 1978 the year after Abba Abba, one of the futuristic narrators writes that ‘Rome is not worth knowing. Not now. There you see what bankruptcy is really like!’ (1985, 167). In Beard’s Roman Women, Rome is described in the very first paragraph by the narrator Ronal Beard as ‘a venal city and a cruel city and a city of robbers’ (Beard’s Roman Women, 9). On the other hand, in the first volume of his autobiography Burgess makes clear the extent to which he felt at home in the city and he writes that ‘I have declared myself a Cittadino mancuniense, cioè romano’ (Little Wilson and Big God, 15). Burgess’s oeuvre demonstrates a remarkably consistent engagement with Rome, from its direct treatment in the Roman novels Abba Abba and Beard’s Roman Women, to its symbolic presence in Burgess’s extensive preoccupation with Catholicism. In terms of my own research at the Foundation, I’m excited to be exploring the depth of Burgess’s relationship with this city, its poets and poetry, particular with regard to the surprising way it allows him to connect Belli to Keats.

A selection of Anthony Burgess’s Roman reading