Belli’s Bible for Blasphemers

-

Martin Kratz

- 22nd March 2016

-

category

- Blog Posts

-

tagged as

- ABBA ABBA

- Belli

- Burgess in Rome

- Keats

- Poetry

- You've Had Your Time

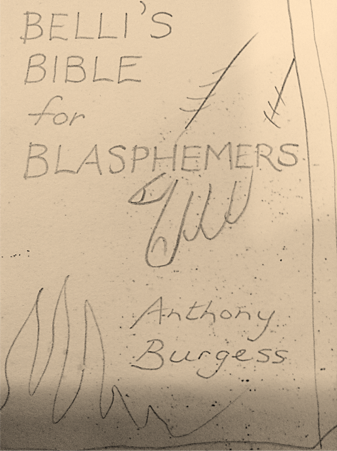

‘Belli’s Bible for Blasphemers’ by Anthony Burgess is in a sense a book that never was. The image (above) depicts Burgess’s sketch of a book cover, doodled in the corner of a draft of a translation of one of the sonnets of G.G. Belli.

Belli was a nineteenth century poet and is famous in Italy as a poet of the Roman vernacular. The illustration and Burgess’s own writings seem to suggest the author’s desire for a standalone volume of Belli translations. Certainly, the translations seemed to constitute a real labour of love for Burgess. In the second volume of his biography Burgess writes that despite Belli having written over 2000 sonnets, ‘I sometimes thought of dedicating my life to their translation’ (You’ve Had Your Time).

Burgess’s translations of Belli were ultimately published in their most complete form as ‘Part Two’ of the novel ABBA ABBA (1977). The novel deals with a fictional meeting between Belli and the dying John Keats. In the novel, the translations of Belli’s poems are framed as being the work of the imagined translator J.J. Wilson (born like the author John Anthony Burgess Wilson in Manchester and only a year apart). Burgess describes the translations as being written in ‘English with a Manchester accent’ (ABBA ABBA). He writes:

The seventy-odd Belli sonnets which I had translated for the second half of the book (and which cunning critics saw were the justification for the first half) had taken more man-hours than I cared to count. (You’ve Had Your Time)

Despite the novel’s ingenuity and careful crafting, Burgess seems to suggest that there is a clear sense of what came first in its composition, the novel or the translations. It is also obvious, which he considered to be the real labour.

Burgess’s preoccupation with Belli’s poetry begins in Rome, where Burgess had moved with his second wife Liana and their son Andrea. While living principally in Bracciano, Burgess also rented a flat at number 16a Piazza di Santa Cecilia in the Roman district of Trastevere (meaning across the Tiber). In Trastevere, there is a well-known statue of a man in a top hat dedicated according to its inscription from ‘the people of Rome […] to their poet, G.G. Belli’. Certainly, it is as a poet of the people that Belli is known, and specifically as a poet of Trastevere. Burgess writes of Belli that ‘he left great verse, unto a little clan’ (You’ve Had Your Time).

Burgess’s preoccupation with Belli is already evident before the publication of ABBA ABBA. In the 1976 novel Beard’s Roman Women, one of the characters, the photographer Paola Lucrezia Belli is a direct descendant of the poet. Furthermore, the protagonist Ronald Beard comes close to having an altercation with a busker who is translating Belli too, and who displays a high degree of territoriality with regard to the project:

“There’s one man who redeems Italy and it’s that top-hatted bugger Belli. You know his work? Blasphemous and scurrilous sonnets. I’m translating them, with the help of the chick I’m shacked up with, as the Yanks put it. I play the guitar for a sort of living. Belli is my real job, not that anybody cares. Do you care?”

“I do as a matter of fact.” Beard felt both relief and disappointment: that task was being removed from him; he was being freed from that task. “I thought of translating him myself.”

“Don’t,” snarled the guitarist. “Leave Belli to me.” (Beard’s Roman Women)

Belli’s immense output was predominantly in the language of the Roman streets, and he took care to transcribe the Romanesco language orthographically. The poems have a panoramic scope in their concerns, but as Burgess himself admits, in his own translation he is ‘restricting [himself] to those that dealt with religious themes and gave full scope to the employment of the blasphemy of the Roman gutters’ (You’ve Had Your Time). This choice is partly informed by his use of a selection of Belli made by Pietro Gibellini in the book La Bibbia del Belli (1974). In this sense, it its difficult not to identify ‘Part Two’ of ABBA ABBA as ‘Belli’s Bible for Blasphemers’.

Readers of Burgess’s work will suspect in Burgess’s interest in blasphemy another expression of his wider concern with the subject of religion. In the essay ‘Belli into English’, Burgess writes that ‘the religious sense goes deeper than reverence and may sometimes be best expressed through blasphemy’. Despite Burgess’s own apostasy, spiritual concerns are central to his work, and ‘Belli’s Bible for Blasphemers’ is recognisable if not as an expression of then as a continued engagement with questions of faith. As Burgess writes of Belli, ‘you can only genuinely blaspheme if you genuinely believe’.