Burgess, Keats and the Sonnet

Anthony Burgess’s 1977 novel ABBA ABBA is a fictional account of the dying days of John Keats. Central to the novel is Keats’s meeting with the Italian poet G.G. Belli. Unable to communicate in a shared language, the two find common ground in the form of the Petrarchan sonnet, which transcends the language barrier between them. The novel concludes with a sequence of Belli’s sonnets translated by Burgess.

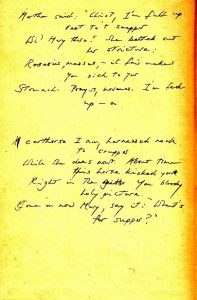

Archival material relating to both Burgess and Keats reveals that the sonnet creates some surprising connections. The Burgess Foundation owns a copy of Burgess’s The Essential James Joyce (1948), in which the pastedown of the endpapers has on it a handwritten draft of one of Burgess’s translations of the poem ‘Marta e Madalena’ by Belli (see above). The poem appears in ABBA ABBA as ‘Martha & Mary’ and the draft in Burgess’s The Essential James Joyce is an early version of the sonnet’s octet. Keats too was known to write sonnets in the endpapers of books he owned. A copy of Paradise Lost for instance, which he eventually gave his neighbour Mrs. Dilke and which is now at the London Metropolitan Archives contains a first draft of the sonnet ‘To Sleep’. The poem is recognisable as a draft: it has only twelve lines (rather than the final version’s fourteen) and has not yet developed some of the published sonnet’s most striking imagery. There are various points at which the draft is difficult to read, as revisions Keats made in the limited space of the book’s inside cover caused the writing to bunch up.

As well as the endpapers of books, Burgess used large pieces of card and calendar diaries for drafts. This practice of writing sonnets, not in a special notebook, but apparently in anything that comes to hand, resonates with one of the central themes in ABBA ABBA: the question of the status of the sonnet. The novel begins with an epigraph from one of Keats’s letter to his friend Benjamin Bailey on 10 June 1818: ‘I would reject a petrarchal coronation—on account of my dying day, and because women have Cancers.’ The rejection of the ‘petrarchal coronation’ refers to the way the sonnet’s exalted position within poetry is challenged in the novel by the poet Belli. Belli is inspired by Keats’s sonnet ‘To Mrs Reynolds’s Cat’—in which the elevated form is combined with a humble subject, the life of an old tomcat—to say:

‘The sonnet can be dragged low, must be dragged low. The time has come to reject its Petrarchal coronation.’

Belli’s own sonnets were written in Romanesco, the language of the Roman streets, and were frequently anti-authoritarian in their content. Belli spoke for a marginalised people against church and state authority in a poetic form that belonged to the same ‘high’ culture the poems were challenging.

Over seventy translations of Belli’s poems by Burgess form the appendix to the novel, but Burgess seems to have had grander aspirations for his translations of Belli’s poems than having to share the stage with the novella about Keats. A sketch of a possible book cover for a standalone collection of Belli’s Bible for Blasphemers can be found next to another set of sonnet-drafts for instance, and Burgess writes that ‘I sometimes thought of dedicating my life to their [Belli’s poems] translation’ (You’ve Had Your Time). Yet, the sonnets’ position as an adjunct to the novella in ABBA ABBA is in at least one sense correct, because the sonnet is a ‘marginal’ form for both Burgess and Keats, if not in terms of its eventual literary value, then at least in the way it was conceived.

The exhibition ‘Rome in the Rain’, exploring Anthony Burgess’s Rome, is on show at the Burgess Foundation until 30 September 2016, 10am to 3pm weekdays and in the evenings during events. Entry is free.