Did Anthony Burgess like Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange?

-

Will Carr

- 24th May 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

Clockwork Controversy:

Myth: Anthony Burgess hated Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film of A Clockwork Orange.

Fact: Anthony Burgess thought the film was a masterpiece and that Kubrick was a great filmmaker. But Burgess resented having to defend the film on television and in print as it was not his own work.

Anthony Burgess had seen Stanley Kubrick’s films and admired them. Praising Paths of Glory, Dr. Strangelove and 2001: A Space Odyssey in his autobiography, he was rather more doubtful about Lolita, in which he felt Kubrick ‘had found no cinematic equivalent to Nabokov’s literary extravagance.’

Burgess worried that the adaptation of A Clockwork Orange would be similarly more concerned with sex and violence than with the language of his novel and miss the point of it. His unease may have been exacerbated by both the rejection of his own linguistically ambitious script adaptation and his lack of involvement with the development of Kubrick’s film.

However, Burgess met Kubrick in London for a private screening of the film prior to its release, and enjoyed it. In his opinion (not shared by his agent Deborah Rogers or his wife Liana, who wanted to leave the screening after ten and eleven minutes respectively):

its brilliance nobody could deny, and some of the brilliance was a film director’s response to the wordplay of the novel. The camera played, slowing down, speeding up; when Alex hurled himself out of a window a camera enacted his attempted suicide by being itself hurled.

He went into detail in a positive review for the Listener after the film went on general release in January 1972:

technically brilliant, thoughtful, relevant, poetic, mind-opening. It was possible for me to see the work as a radical remaking of my own novel, not as a mere interpretation, and this — the feeling that it was no impertinence to blazon it as Stanley Kubrick’s Clockwork Orange — is the best tribute I can pay to the Kubrickian mastery.

Burgess’s respect for Kubrick’s film is clear, but the question of ownership over A Clockwork Orange, and responsibility for it, may be the source of the myth that Burgess ultimately hated the adaptation.

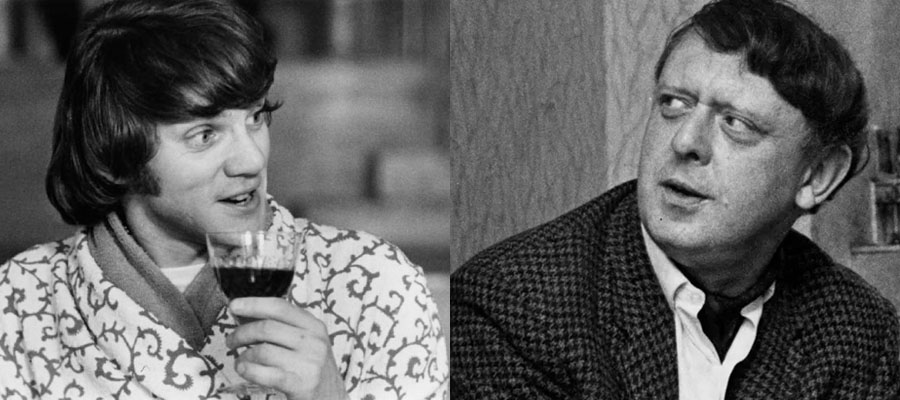

Burgess joined Malcolm McDowell for a publicity tour in New York to promote the film, and, during a week of challenging interviews from influential journalists, began to resent having to justify a work that was no longer entirely his own. Burgess wrote later:

I was not quite sure what I was defending — the book that had been called ‘a nasty little shocker’ or the film about which Kubrick remained silent […] Kubrick’s achievement swallowed mine, whole, and yet I was responsible for what some called its malign influence on the young.

In any case Burgess did not feel that his book, or for that matter Kubrick’s film, could be said to have a malign influence: reflecting on the question many years later, he wrote that ‘action was anterior to art, aggression was built into the human system and could not be taught by a book, film or play […] From the film of A Clockwork Orange youth did not learn aggression: it was aggressive already. What it did learn was a style of aggression, a mode of dressing violence up in a new way.’

That Kubrick himself was absent from the New York press tour, as Burgess put it, ‘paring his fingernails in Borehamwood’ while Burgess and McDowell did the punishing studio rounds, did not help.

Burgess was also infuriated by the later publication of a book called Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, an illustrated version of Kubrick’s screenplay: he saw this as an appropriation of his work and gave it a poor review in the Library Journal. His view was ultimately that he had been altogether badly used by the film industry, feeling that he had not shared in the commercial success of the adaptation.

And as the years passed, Burgess became impatient with journalists who wished only to discuss A Clockwork Orange, and in particular Kubrick’s film version, rather than Burgess’s many other books. Yet, despite these frustrations, he never regarded Kubrick’s film as anything less than a brilliant work.

This ‘Clockwork Controversies’ series, in which we will examine myths surrounding Anthony Burgess’s most famous book, is one of several ways in which the Burgess Foundation is marking the 50th anniversary of Stanley Kubrick’s film of A Clockwork Orange.

Find out more about the creation, meaning and legacy of Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange elsewhere on our site.