The Clockwork Collection: The Glorious Ninth and other records

-

Anna Edwards

- 25th June 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

2021 marks the 50th anniversary of the first release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, and 60 years since Anthony Burgess completed his most famous novel.

To celebrate the anniversary, we present an online series called The Clockwork Collection, with a focus on A Clockwork Orange.

Each month, we’ll be sharing a highlight from the Burgess Foundation’s archive. Expect literary manuscripts, vinyl, books, audio, journalism, music scores, photographs and more. For more information on the items discussed in the series, please contact our archivist.

The Clockwork Collection: The Glorious Ninth and other records

Music fills the pages of A Clockwork Orange. Works by real and imagined classical composers provide the soundtrack to fantasy, robbery, and murder in the novel and its subsequent film adaptation.

This soundtrack challenges the notion that music is a source of intrinsic goodness, and encourages the reader to question whether Alex, the novel’s violent ‘Humble Narrator’, can indeed be considered to be ‘all bad’. Alex’s ability to choose his actions freely, and to appreciate language and beauty, are presented by Burgess as proof of Alex’s humanity. When the state removes these attributes, it removes Alex’s soul.

Burgess draws on his own musical influences to enrich his exploration of morality and there is much in Alex’s musical tastes that mirrors Burgess’s own. Alongside his many writings about music, Burgess’s library and vinyl collection provide a valuable insight into this world.

Both Burgess and Alex share a love of Classical- and Romantic-era composers and a disdain for pop music. Among the 640 records belonging to Burgess and his family which are preserved within the Burgess Foundation’s vinyl collection, more than half are classical, with compositions by Bach, Mozart, Mendelssohn, and Beethoven among the most prominent.

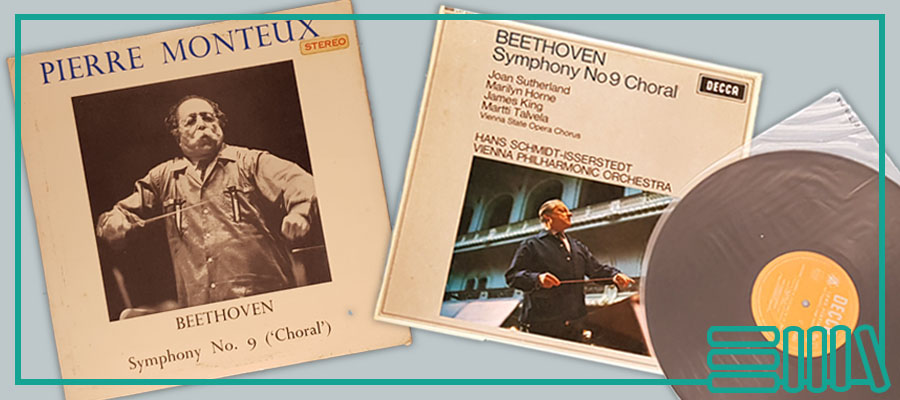

Burgess owned recordings of Beethoven’s nine symphonies, as well as copies of his piano music and string quartets. There are two recordings of Beethoven’s ‘Glorious Ninth’, Alex’s favourite piece of music, described by Burgess as Beethoven’s ‘triumph’ in his article ‘Anthropomorphically Analytical’, published in the Times Literary Supplement on 1 May 1981.

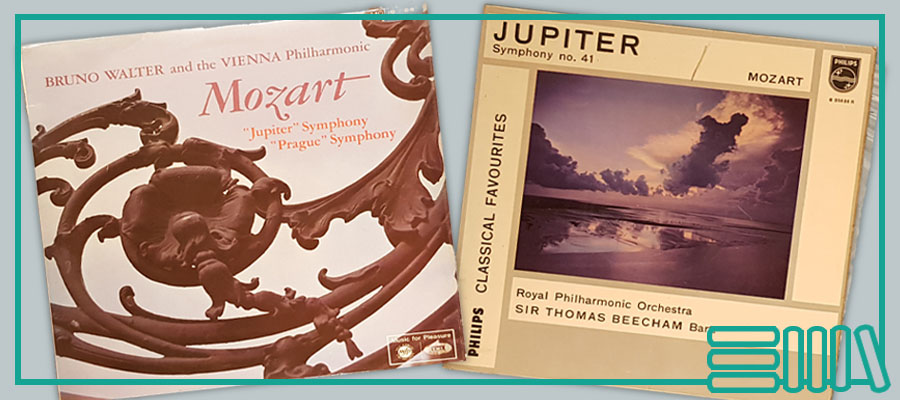

The vinyl collection includes several other individual pieces mentioned in A Clockwork Orange, such as two copies of Mozart’s Jupiter symphony and one copy of Bach’s Cantata No. 140 (‘Wachet Auf’).

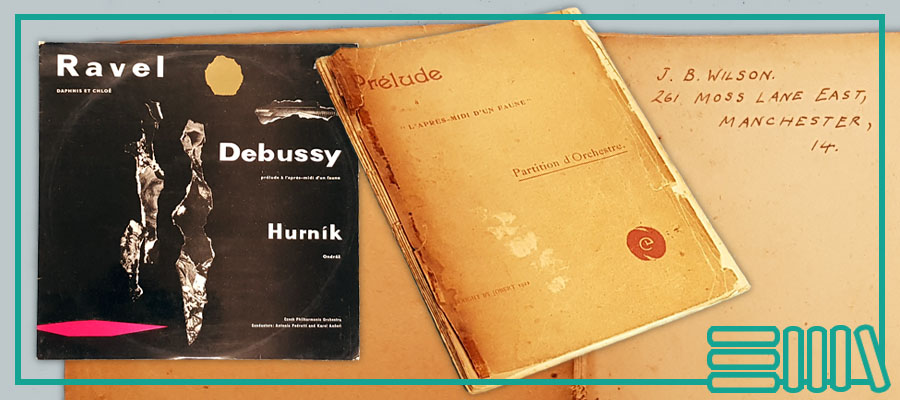

There are twelve recordings of music by Debussy, including two copies of his Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. Although Debussy isn’t mentioned explicitly as one of Alex’s favourite composers, he is, as Paul Phillips notes in A Clockwork Counterpoint, present in ‘a very nice malenky string quartet, my brothers, by Claudius Birdman.’ Birdman, Phillips explains, is likely to refer to Dutch biologist Louis Philibert le Cosquino de Bussy (1879-1943), and is one of several imagined composers and compositions within the novel. Other fictional examples include Adrian Schweigselber, Friedrich Gitterfenster and Otto Skadelig.

The Foundation’s collection of printed materials allows further exploration of Burgess’s musical influences. The printed books include scores, biographies, and critical studies relating to many of his favourite composers. There is a miniature score of Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, a particularly rare survival from Burgess’s early life in Manchester. The score was published by Jean Jobert in the 1920s, and its yellowing appearance and fragile condition testify to its heavy use. Unusually, we know exactly when and why Burgess purchased this particular item. Not only has Burgess inscribed the score with his name and postcode — ‘J.B. Wilson, 261 Moss Lane East, Manchester 14’ (see below) — he also provides an account of the seminal event that caused him to buy it. In This Man and Music, Burgess describes building a crystal set radio as a boy and hearing Debussy’s Prélude for the first time. The experience was, he said, a kind of epiphany that would drive him to pursue composition: ‘There is, for everybody, a first time. A psychedelic moment, as they say or used to say nowadays, an instant of recognition of verbally inexpressible spiritual realities, a meaning for the term beauty.’ He rushed out to buy the score with money given to him for his fifteenth birthday.

Although Burgess doesn’t recreate this moment exactly in A Clockwork Orange, the bliss that Alex feels when hearing a new violin concerto by Geoffrey Plautus closely recalls his own experience: ‘Oh it was gorgeousness and gorgeosity made flesh. The trombones crunched redgold under my bed, and behind my gulliver the trumpets three-wise silverflamed, and there by the door the timps rolling through my guts and out again crunched like candy thunder. Oh, it was wonder of wonders.’

Burgess’s love of music does not only appear in A Clockwork Orange and he draws on his musical grounding and preferences in several other novels. For example, The Pianoplayers is full of music from Burgess’s youth and, in Enderby Outside, he presents a dig at The Beatles through a fictional band, The Crewsy Fixers. Its lead singer, Yod Crewsy, even adopts Russian slang at one point, like Alex, telling his audience that he has put together a book of (plagiarised) poems to ‘show that we do like think a bit and the kvadrats, or squares which is what some of you squares here would like call yourselves, can’t have it all their own way.’ But it is Burgess’s love of Beethoven which offers him the most inspiration. This comes across, perhaps most famously, in Napoleon Symphony, Burgess’s fictionalised life of Napoleon Bonaparte in four ‘movements’, structured according to Beethoven’s Eroica.