The fictional afterlives of Anthony Burgess, part six

-

Burgess Foundation

- 1st December 2011

-

category

- Blog Posts

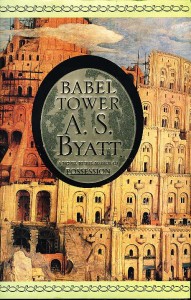

Anthony Burgess’s most extensive fictional appearance is in AS Byatt’s 1996 novel Babel Tower, the third book of a tetralogy that charts the life of  her character Frederica Potter. Babel Tower is set in the 1960s, during the first waves of the counterculture, and much of the novel deals with legal actions, one of which is an obscenity trial at which Anthony Burgess appears as an expert witness.

her character Frederica Potter. Babel Tower is set in the 1960s, during the first waves of the counterculture, and much of the novel deals with legal actions, one of which is an obscenity trial at which Anthony Burgess appears as an expert witness.

Before the trial Burgess appears off-stage, in his role as literary critic. Byatt reports a putative Burgess review of Babble Tower, the subject of the obscenity trial, in which the familiar Burgessian ‘battle between St Augustine, the Bishop of Hippo, who believed that fallen man was naturally evil, and Pelagius, the hopeful Hibernian heretic who believed that man could by free will and reasonable exercise of virtue achieve salvation’ is described.

Reviewer Burgess ‘portentously, mischievously’ suggests that Babble Tower ‘is in great danger of being prosecuted for obscenity’, and so it transpires. A defence committee is convened, featuring Byatt’s protagonist Frederica, and ‘it is agreed that Anthony Burgess shall be sounded out, since he wrote well of the book.’

Burgess follows two academics onto the witness stand. ‘He praises Babble Tower in musical terms: brio, appassionata, fugue‘ and is described during cross-examination by ‘Sir Augustine’ (who is opposed on the defence by ‘Godfrey’ Hefferson-Brough) as a ‘daring writer’ who takes risks for his art. The courtroom scenario evokes a similar obscenity case in Earthly Powers, and features a talkshow guest version of Burgess, the convivial debater of public aesthetics. AS Byatt is clearly influenced by Burgess and writes highly of his work elsewhere, though he is not mentioned in the acknowledgements to this novel.

The most recent fictional Burgess comes with an added disguise. It is not John Wilson’s usual nom-de-plume ‘Anthony Burgess’ who plays a supporting role in Matthew Asprey’s debut novella Red Hills of Africa, but a lesser-known pseudonym, Joseph Kell. The Australian media critic posits an alternative universe in which Kell (rather than Burgess) lived on into his eighties in Marrakesh, writing novels such as as Skin and Blister and Instruments of Darkness. A gregarious Kell invites an American academic home to interview him, and she arrives with a retinue of spurned husband, a one-night-stand and her one-night-stand’s one-night-stand.

He discusses ‘the confiscation of his Maltese villa and his friendship with Princess Grace’ and treats them all to a round of his Hangman’s Blood cocktail, which knocks most of the guests for six. Asprey’s novella is a jeu d’esprit, at once satirising the academy in terms not dissimilar to David Lodge while simultaneously capturing some of the brio and comedy of Burgess’s own depictions of the tourist let loose in Morocco in Enderby Outside.