Anthony Burgess and Margaret Thatcher

-

Burgess Foundation

- 8th April 2013

-

category

- Blog Posts

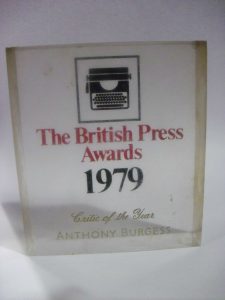

Anthony Burgess encountered Margaret Thatcher only once. At a lunch at the Savoy in London she presented him with the 1979 ‘Critic of the Year’ award, which is a small plastic plaque, and a cheque for two hundred pounds.

Burgess’s thoughts on Thatcher are recorded in his essay ‘Thoughts on the Thatcher Decade’, written in 1989 and reprinted in the collection One Man’s Chorus (1998). He presents Thatcher as pursuing a vigorous and radical free market ideology: ‘[for Thatcher] the State is not there to look after people. People must make money and learn to look after themselves … The rich have had far bigger tax cuts than the poor. This is in accordance with a philosophy that rewards the makers of money. There is something criminal about being poor.’ Burgess’s attitude towards the economics of Thatcherism is a little unclear, as despite these apparently sympathetic remarks towards the poor he characteristically still manages to complain about high tax rates; and this even though he does not pay them himself, having by 1989 lived in Monaco for a dozen years.

Burgess is particularly exercised by the narrow focus and limited values that he finds in Thatcherism. ‘Some things cannot be considered in terms of a market economy, and the chief of these things is education … The ruling philosophy is utilitarian. Education is of little value unless, directly or indirectly, it leads to the expansion of the Gross National Product. Of what use is the study of history, philosophy, archaeology? … Mrs. Thatcher presumably sees no use in the teaching of moral values. There is little evidence in contemporary British life that it is considered better to help the sick and suffering than to kick them in the face.’ Burgess was of course a teacher himself, in the Army teaching squaddies ‘The British Way And Purpose’, and later as an English teacher in Malaya and Brunei; his lively and still useful pedagogical writings including English Literature: A Survey For Students (1958) and Joysprick: An Introduction to the Language of James Joyce (1973) show how much he valued education and learning for its own sake.

However, Burgess’s main criticism of Thatcher is that ‘She is a notorious philistine. She is never to be seen at concerts, plays or operas. She reads best-sellers. She recently confided with a kind of pride that she had just re-read The Fourth Protocol by Frederick Forsyth. Re-read, note. She is unintellectual.’ This, for Burgess, is unforgivable. Thatcher is a symbol of the unimaginative consumerism that blights the England he has left behind, and of a culture which refuses to honour him. The 1979 ‘Critic Of The Year’ award was perhaps the closest he came to the recognition that he craved from the British establishment, and remained one of the only prizes that he won in Britain. He recalls in You’ve Had Your Time: ‘We were photographed together smirking. This was not quite the honour I wanted.’