The Clockwork Collection: the music of Wendy Carlos and A Clockwork Orange

-

Will Carr

- 17th December 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

2021 marks the 50th anniversary of the first release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, and 60 years since Anthony Burgess completed his most famous novel.

To celebrate the anniversary, we are presenting an online series called The Clockwork Collection, with a focus on A Clockwork Orange.

Each month we’ll be sharing a highlight from the Burgess Foundation’s archive. Expect literary manuscripts, vinyl, books, audio, journalism, music scores, photographs and more. For more information on the items discussed in the series, please contact our archivist.

The Clockwork Collection: the music of Wendy Carlos and A Clockwork Orange

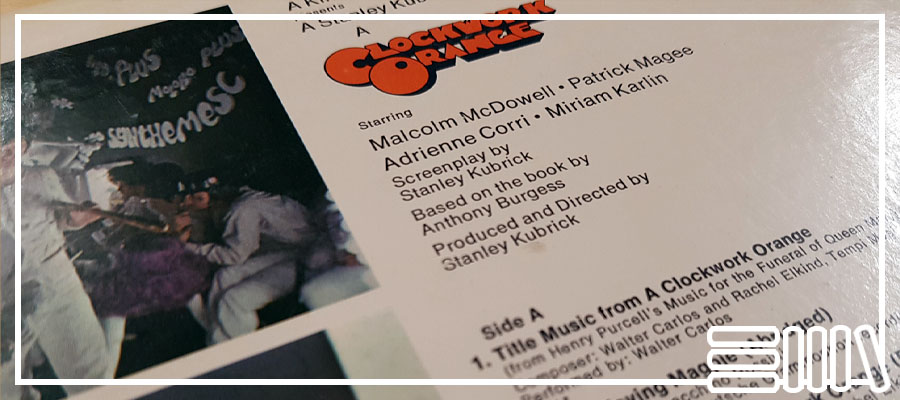

Two records featuring the music of Wendy Carlos are in Anthony Burgess’s vinyl collection: Switched-On Bach (1968) and Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1972), the official soundtrack of the motion picture.

Wendy Carlos had studied music composition at Columbia University in New York, and was a student of the electronic music pioneer Vladimir Ussachevsky. It was here that she met Robert Moog, whose synthesisers would revolutionise electronic music. Working with him on the development of his early technologies in the mid-1960s, Carlos gained access to the latest equipment and tools for composition and performance. This creative relationship and Carlos’s skill with the Moog system led ultimately to her debut album Switched-On Bach, a collection of pieces by J.S. Bach that popularised synthesiser music and sold more than a million copies on its way to winning three Grammy awards. Carlos’s approach managed to harness the range of sounds of the Moog, with its bleeps, buzzes and drones, to make highly expressive and nuanced music: the overall effect was accessible and engaging to listeners not usually interested in classical repertoire.

This success was followed by The Well-Tempered Synthesizer (1969), another collection of classical works with pieces by Bach, Handel, Scarlatti and Monteverdi. Carlos then worked on a version of the final choral section of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, as well as ‘Timesteps’, both pieces designed to showcase the spectrum follower, a device that turns the human voice into an electronic signal. During this time she began reading A Clockwork Orange, and found that the dystopian mood of the book had correspondences with her new work. Describing ‘Timesteps’ as ‘an autonomous composition with an uncanny affinity for Clockwork’, she deliberately completed it to complement the novel. Carlos and her long-time producer Rachel Elkind then sent ‘Timesteps’ and the Beethoven arrangement to Stanley Kubrick, who immediately hired them to create the soundtrack for his forthcoming film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange.

Carlos’s soundtrack left behind the virtuoso and cheerfully baroque renditions of Bach in favour of a far darker and more challenging soundscape. The opening theme, a synthesised version of ‘Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary’ by Henry Purcell, powerfully heightens the intimidating first appearance of Alex and the droogs and Alex’s menacing voiceover; the second and fourth movements of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony receive similar treatment, and Rossini’s ‘William Tell Overture’ is mechanically sped up to a sickening degree. ‘Timesteps’ appears too, though only very briefly in the film, as Alex is strapped to his chair to undergo Ludovico’s Technique. The soundtrack album contains almost five minutes of it, with electronic whines, white noise, explosions and disembodied voices culminating in a terrifying chord. The total effect is highly troubling and entirely appropriate to Kubrick’s, and Burgess’s, disturbing vision.

Burgess recognised the importance of the music in Kubrick’s film, describing it in his memoirs as ‘not just an emotional stimulant but a character in its own right.’ He went on to reflect that ‘if the pop-loving young could be persuaded to take Beethoven’s Ninth seriously – even in its Moog form – then one could soften the charge of scandal with the excuse of artistic uplift.’ Carlos’s approach was of course in itself scandalous, in that it disrupted the norms of classical music and repurposed it for a new generation of artists and composers.

Three months after the release of the official soundtrack Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, Carlos released Walter Carlos’ A Clockwork Orange (reissued in 2000 as A Clockwork Orange: Wendy Carlos’s Complete Original Score): this brought together all the electronic music Carlos composed for the film but was not ultimately used, including a complete version of ‘Timesteps’, an electronic arrangement of Rossini’s ‘The Thieving Magpie’ and an original piece ‘Country Lane’. ‘Country Lane’ incorporates further elements of Rossini as well as a medieval chant ‘Dies Irae’, and a suggestion of the song ‘Singin’ in the Rain’. During the 1970s there were several more albums of her distinctive versions of classical works, followed by her second and final collaboration with Kubrick on The Shining in 1980.

Burgess may have despised pop music, but by 1980 he did own a synthesiser, which is also part of the collection at the Burgess Foundation. This is a Casiotone 701, an analogue synthesiser (in this respect like the Moog) that features voices, drums, Casio auto-accompaniments, and the unusual ability to read bar code charts to play back songs and arrangements. No recordings of any experimental approaches to electronic music by Burgess seem to exist, but he did compose a complete cycle of preludes and fugues, The Bad-Tempered Electronic Keyboard. Like Wendy Carlos’s The Well-Tempered Synthesizer, his title recalls Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier from 1722.