Anthony Burgess and Russia

-

Andrew Biswell

- 6th April 2022

-

category

- Blog Posts

2022 is the sixtieth publication anniversary of A Clockwork Orange, which appeared in Britain in May 1962. In the first in a series of articles about the publishing history and critical reception of the novel, we consider the book’s Russian context.

Many readers have wondered why Anthony Burgess decided to use Russian as the basis for his fictional slang in A Clockwork Orange. The answer is a complicated one, and it has surprisingly little to do with politics.

Russia proved to be a fertile subject for Burgess’s fiction, although the publication history of his novels in the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) is partly a story of censorship and official condemnation. When Burgess sailed to Russia with his wife Lynne in June 1961, he intended to gather copy for a travel book which had been suggested by his London publishers, William Heinemann, who had paid his travel expenses in advance. The non-fiction book was never written, but three major novels emerged from his visit to Leningrad (now known as St Petersburg): A Clockwork Orange, Honey for the Bears, and Tremor of Intent, written as a parody of Cold War thrillers by Len Deighton and John Le Carré.

It is clear from You’ve Had Your Time, the second volume of Burgess’s autobiography, that he wanted to visit Leningrad because he was interested in pre-revolutionary Russian literature, especially the poetry of Pushkin and the novels of Dostoevsky. He opposed the Soviet regime and, like many people of his generation, had been appalled by the events of November 1956, when Russian tanks had rolled into Budapest to crush the anti-Communist protests. Learning to speak Russian, as he did shortly before his visit, offered a way for Burgess to communicate directly with ordinary people, bypassing the channels of Soviet propaganda.

A notebook in the Burgess collection at the University of Angers shows us exactly how he did it. He devised a home-made system of mnemonics, with pictures to jog his memory. For example, the Russian word ‘chelloveck’ — meaning a man or a person — appears in the notebook next to a drawing of a cello with a human face. By using this system, and listening to a series of vinyl records to improve his Russian accent, he was able to make swift progress with learning the language.

Burgess had signed a contract to write a novel titled A Clockwork Orange in November 1960, but he had been struggling to invent an authentic-sounding slang for his futuristic juvenile delinquents. The solution emerged from his study of Russian in the spring of the following year. As he recalled in You’ve Had Your Time: ‘The vocabulary of my space-age hooligans could be a mixture of Russian and demotic English, seasoned with rhyming slang and the gipsy’s bolo.’

Before he set off for Russia, he compiled the basic vocabulary of his fictional language and decided to call it ‘Nadsat’, borrowing the Russian word meaning ‘teen’. Although Alex in the book is completely apolitical, some readers have speculated (wrongly) that Burgess must have been a communist sympathiser because he decided to use Russian.

Not long after he returned to England, Burgess set down his impressions of Russia in an essay, ‘The Human Russians’, published in the Listener on 28 December 1961. Although he had gone to Leningrad expecting to find a cold, totalitarian state where all emotion had been crushed out of the people, what he found was ‘tremendous warmth’. Ordinary Russians were welcoming, he said, and the food was ‘coarse and delicious’. The pervasive smells of bad drains and cheap tobacco recalled his early years in Manchester. He also saw violent, well-dressed teenage boys who reminded him of the Teddy Boys at home in Britain. In his essay, Burgess represents Leningrad as a place of lawless drunkenness, where no attempt was made to deal with low-level criminality. ‘It is my honest opinion,’ he wrote, ‘that there are no police in Leningrad.’ Nevertheless, he wondered if the secret police were kept busy with sniffing out political crimes.

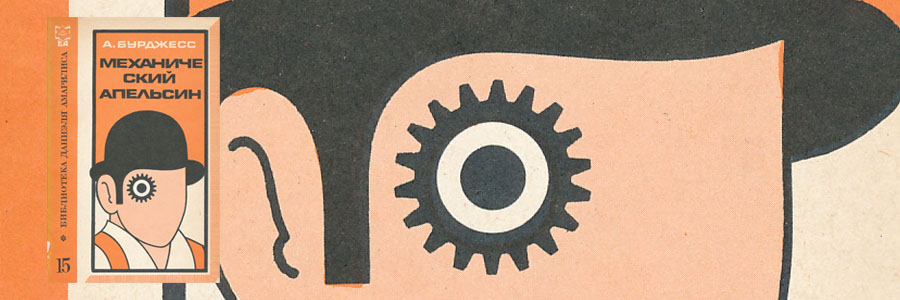

Various difficulties with censorship were encountered when it came to publishing Burgess’s novels in Russian. From the beginning, it was unlikely that a subversive novel like A Clockwork Orange, with its sceptical depiction of a tyrannical state, would be welcomed by the censors in Soviet Russia. In 1977, the book’s first Russian-language publisher solved this problem by printing the book in Tel Aviv and secretly shipping copies into Russia.

Curiously, the Kubrick film adaptation seems to have been available in Moscow in the 1970s, some years before the novel itself was approved for publication. Perhaps the film censors were more liberal than their literary counterparts, or else the anti-state politics of the novel were felt to have been sufficiently watered down by Kubrick.

The more relaxed climate of the Gorbachev era made it possible for Russian-language publishers to distribute a handful of Burgess books more openly during the final years of the Soviet system. A second translation of A Clockwork Orange by Yevgeny Sinelshchikov appeared in 1991.

Two other books translated in this period contained a set of black and white illustrations: the Russian editions of The Wanting Seed and Tremor of Intent were adorned with bold and flavoursome images (see Tremor of Intent image at the foot of this page).

In 1987, two years before the collapse of the Berlin Wall, Burgess received a letter from Vladimir Abarinov, editor of the Soviet journal Literaturnaya Gazeta, who requested an article about ‘problems of contemporary Western youth’. Burgess replied, apologising for not writing in Russian because his typewriter did not have the right Cyrillic characters. He mentioned in passing that his grandfather had been a friend of Karl Marx when they both lived in Manchester: an unlikely boast, and a good example of his tendency to tell the recipient of a letter what he thought they wanted to hear. He revealed himself to be a capitalist individualist by requesting a fee for his contribution to the journal.

Publication of Burgess’s work has continued in Russia since the demise of Communism. In recent years there have been new translations of The Wanting Seed, 1985, Inside Mr Enderby and Nothing Like the Sun (published under the misleading title Shakespeare in Love). At the time of writing, further Russian translations are planned, and a new stage production of A Clockwork Orange has been announced.

It is unlikely that Burgess’s work, characterised by its strong opposition to censorship and a sceptical view of politics, could encourage support for a repressive regime in the Kremlin. And it’s worth noting that nearby countries such as Ukraine, Finland, Poland, Lithuania and Estonia have been quick to see the benefits of publishing A Clockwork Orange and other books by Burgess.

Asked in the 1980s about the legacies of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, Burgess replied that political leaders and their ideologies come and go, whereas literature exerts a permanent influence on its readers. Recent events in Russia and Ukraine have given us cause to reflect on those words.