Anthony Burgess, Jorge Luis Borges and Shakespeare

-

Andrew Biswell

- 27th April 2022

-

category

- Blog Posts

-

tagged as

- America

- Anglo-Saxon

- Anthony Cronin

- Argentina

- Bloomsday

- Christopher Marlowe

- Dictionary of Borges

- Dublin

- Enderby's Dark Lady

- espionage

- Ireland

- James Joyce

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Michael Ayrton

- Modern Fiction Studies

- Observer

- Paul Theroux

- Plain Wrapper Press

- Samuel Coale

- Shakespeare

- short stories

- Switzerland

- Talks and lectures

- The Listener

- USA

- Washington

- Will and Testament

When Jorge Luis Borges met Anthony Burgess for the first time, Borges was 77 years old and at the height of his international fame. He had been blind for 23 years. Burgess had just turned sixty, and was much in demand as a screenwriter and public speaker. The venue for their historic meeting was the Embassy of Argentina in Washington DC, a grand, French-style building on New Hampshire Avenue in the Dupont Circle district of the city.

This first meeting is quite well known, not least because Burgess wrote about it in both volumes of his autobiography. In Little Wilson and Big God, he says that he and Borges, believing themselves to be surrounded by secret agents, decided to have a conversation in Anglo-Saxon:

BURGESS: Nu we sculan herian heofenrices weard.

BORGES: Meotodes meahte ond his modgeþanc.

This exchange left the listening spies baffled: what was being said, and which language was being spoken? In fact they were reciting the hymn of the poet Caedmon, one of the earliest surviving pieces of literature in English. Borges — an enthusiastic linguist, like Burgess — had studied Anglo-Saxon poetry during his school education in Switzerland. They deployed their shared love of Old English as a private joke, and as a means of secret communication. As Burgess recalled, ‘We continued to the end of the poem in linear antiphony.’

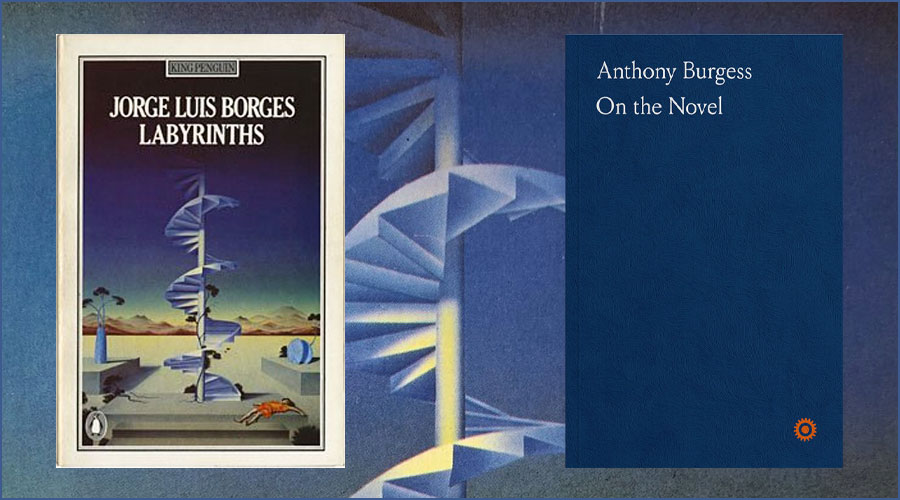

Burgess was so pleased with this story that he repeated it, with minor variations, in You’ve Had Your Time, the second volume of his autobiography. But the literary relationship between the two writers extended beyond this famous anecdote. The earliest reference to Borges in Burgess’s work appeared on 23 May 1963, when he reviewed a BBC television documentary in which the Argentinian writer had been interviewed. Writing in the Listener, Burgess praised the programme and approved of Borges’s statement that his stories were short because he was worried about spoiling them by making them longer.

Burgess’s comments were published just a year after the first English translations of Borges had appeared in book form. There are other substantial references to Borges in his critical writing, and these confirm that Burgess had a good working knowledge of the stories collected in Labyrinths and Ficciones. In his non-fiction book On the Novel, Burgess compared Borges to other major writers who had mastered short forms, such as Ronald Firbank, Evelyn Waugh and Samuel Beckett.

Reviewing Michael Ayrton’s Fabrications for the Observer on 26 November 1972, Burgess wrote: ‘I’d call Fabrications a manifestation, insolent yet innocuous, of supererogatory though sporadically inventive Borgesian pastiche.’ He identified Borges’s story ‘Examination of the Work of Herbert Quain’ as the influential work which seemed to stand behind Ayrton’s fictional experiment. More generally, Burgess had a nagging sense that Borges should probably not be emulated by people less talented than him. Interviewed by Samuel Coale for Modern Fiction Studies in 1981, he stated that ‘Borges has done his work,’ implying that it was time for other writers to move beyond imitation of his techniques.

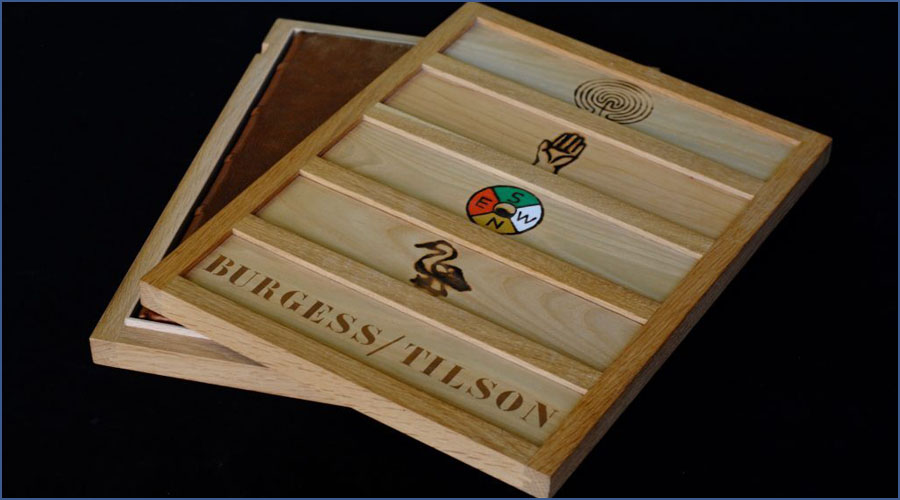

The occasion for their meeting in Washington was the international congress of the Shakespeare Society of America in April 1976, where Borges and Burgess gave keynote lectures on 21 and 23 April. Speaking in the Presidential Ballroom of the Statler-Hilton Hotel, Burgess gave a wide-ranging talk in which he performed passages from Hamlet in Elizabethan pronunciation and read a section from his story, ‘Will and Testament’, published a year later by the Plain Wrapper Press in Verona (see image below), and later reprinted in Enderby’s Dark Lady. He concluded thus:

Shakespeare has no faith, no philosophy. He has all the faiths and philosophies, or rather his characters have between them. He has merely one harmless obsession — to eternise the name Shakespeare through his son and his son’s sons. Here he fails, and he cannot know that the name Shakespeare will live on for a reason unconnected with blood. Ben Jonson publishes his Works. Shakespeare is uninterested in publication — unless it be to save the true text from the pirates. His plays are published seven years after his death by a couple of colleagues, one of whom had been a grocer. The works are great, but the man himself seems ordinary enough.

Speaking in English and without notes, Borges gave a characteristic talk under the title ‘The Riddle of Shakespeare’. He discussed conspiracy theories about the authorship of Shakespeare’s works and refuted the notions that Shakespeare was ‘really’ Francis Bacon or Christopher Marlowe. He ended with an argument about the impossibility of fully understanding Shakespeare:

He is slipping away almost all the time. He goes from one thing to another. In the same sentence, he uses words with different connotations. ‘To sleep, perchance to dream — aye, there’s the rub.’ We recognize the different connotations, as we should. At the same time, we know that we are missing many things. For, of course, Shakespeare is too vast for us.

The next encounter between Burgess and Borges took place in June 1982. Both writers were invited to the James Joyce centenary celebrations in Dublin at the suggestion of Anthony Cronin, the cultural adviser to the Irish Taoiseach, Charles Haughey. Burgess delivered a memorable lecture on Joyce at Dublin Castle on the evening of 16 June. This is how Burgess recollected Borges’s contribution to the same event:

He gave a little talk about Joyce’s importance after a banquet which was, in the Irish manner, highly bibulous, and most of its guests, who did not know who the hell he was, talked throughout his discourse. That, we may say, was the response of the great philistine world. Borges remains a taste to be cultivated, a name known and even feared but not destined to be popular.

The two writers spent time together at the Shelbourne Hotel on St Stephen’s Green, and Burgess later remembered a few fragments of their conversation. ‘What a beautiful word is mist,’ said Borges. Burgess thought better of pointing out that in German it means ‘manure’.

Burgess’s considerable admiration for Borges appears to have been fully reciprocated. When Paul Theroux met Borges in Buenos Aires during his South American travels, later published as The Old Patagonian Express (1979), Borges told him: ‘Anthony Burgess is very good — a very generous man, by the way. We are the same — Borges, Burgess. It’s the same name.’ This is confirmed by a 1977 letter from Burgess to his Spanish translator, signed ‘Antonio Borges’.

One other posthumous encounter is worth recording. In 1990, four years after Borges had died in Geneva, Burgess was asked to write the foreword to A Dictionary of Borges, compiled by Evelyn Fishburn and Psiche Hughes, and published by Colin Haycraft at Duckworth. This elegant A to Z reference volume is an excellent companion to Borges and his strange metafictional world. In the foreword, Burgess expresses his deep admiration and pays tribute to Borges as a great maker of fictions. He says that the work was built on a foundation of reading, adding that Borges had read more widely, and in more languages, than any other creative artist who came before him, including Joyce. Summing up Borges’s achievement, Burgess writes:

His ficciones, delicate, enigmatic, metaphysical, represent some of the most exquisite probing into the reality that twentieth-century literature has seen. […] His short stories are not the product of short-windedness, in the manner of the composer Anton Webern, but examples of a wholly original genre whose bulk and resonance depend on an elected brevity.