Inside the archive: Preserving Debussy

-

Anna Edwards

- 12th January 2023

-

category

- Blog Posts

Preserving the Burgess Foundation’s collection of books, archival records, and objects is an ongoing challenge. Time spent in countries such as Malaya and Brunei, as well as travels throughout Europe, America, and the UK, brought with it exposure to termites, damp, floods, heat, and sunlight. Such conditions, coupled with frequent handling and the passage of time, have taken their toll on the valuable items in our care.

Since 2011, we have been working with Formbys, a specialist in book conservation and restoration, to treat items within our library. This vital work has been supported by contributions to the Foundation’s Friends’ scheme and by other donations to the archive.

The following titles have recently been restored:

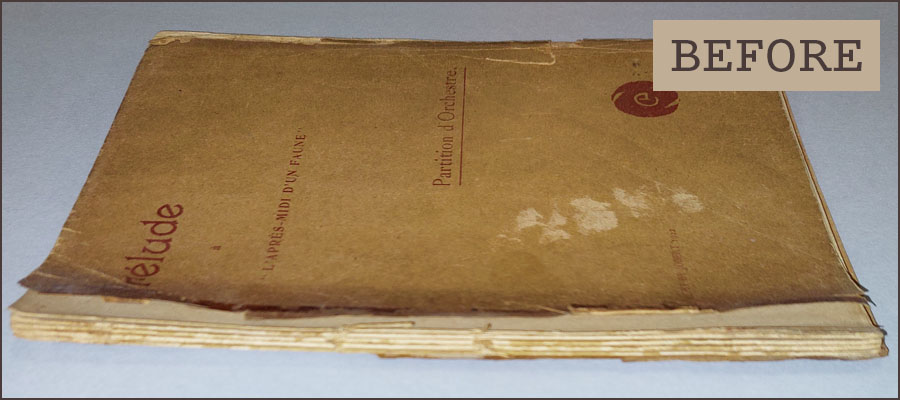

• Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, a minature score published by Jean Jobert in c.1922

• The Essential James Joyce, edited by Harry Levin (Jonathan Cape, 1948)

• Selected Essays by T. S. Eliot (Faber and Faber, 1934)

• Chamber Music by James Joyce (Egoist Press, 1923)

• Teach Yourself Russian by Maximilian Fourman (English Universities Press, 1958)

• La Bibbia del Belli, edited by Pietro Gibellini (Adelphi, 1974)

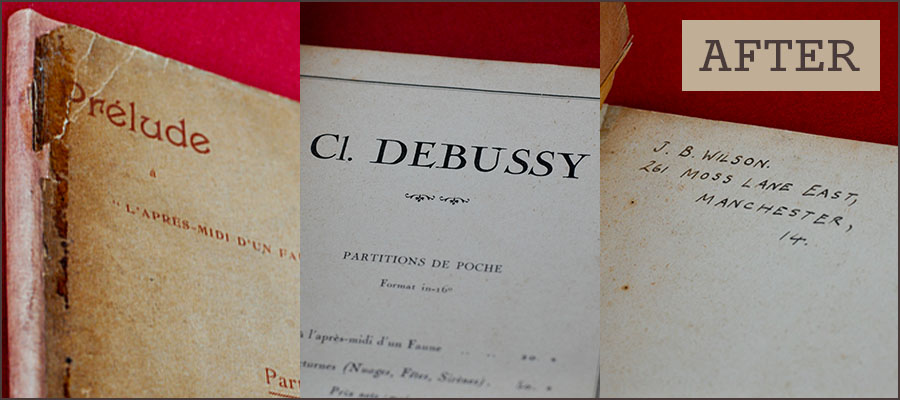

The treatment of these books includes surface cleaning, repairs to bindings, rebacking spines, and the use of specialist solvents. Thanks to this important work, we are pleased to be able to make these volumes available to visiting researchers once more.

In this, the first of a series of posts about books which have been restored by Formbys, we focus on a miniature score of Claude Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, a remarkable survival from Burgess’s early life.

At first glance, the mass-produced and unannotated pocket score may appear insignificant, but it plays a key part in Burgess’s story. In This Man and Music (1982), Burgess describes the first time he heard the piece of music as a boy on his crystal set radio as a kind of epiphany:

There is, for everybody, a first time. A psychedelic moment, as they say or used to say nowadays, an instant of recognition of verbally inexpressible spiritual realities, a meaning for the term beauty.

He describes rushing out to buy the score with money given to him for his fifteenth birthday, and he has carefully and neatly inscribed the inside cover: ‘J.B. Wilson, 261 Moss Lane East, Manchester 14’ (John Burgess Wilson was Anthony Burgess’s original name).

The ‘quiet impact of Debussy’s orchestra’ sparked a lifelong passion for music, particularly classical music: for listening to it; for learning about it; and for composition. Debussy was a major influence on Burgess’s earliest musical works, none of which have survived in their original form. Fortunately, we are provided with a glimpse of this period in a nocturne for oboe and piano, which is dated 1987 and bears the handwritten contextual note ‘Composed when I was 15 years old and suddenly remembered at the age of 70.’

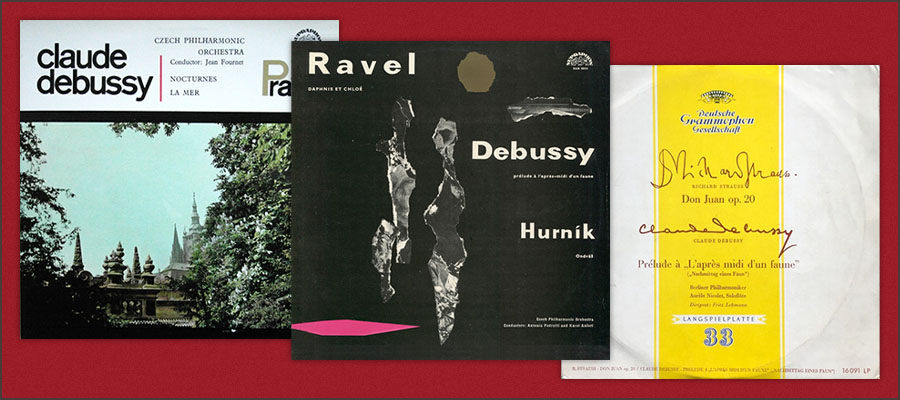

Although Burgess would develop passions for other composers as his musical education progressed, Debussy remained a firm favourite. Burgess’s vinyl collection, preserved within our archive, contains twelve recordings of music by Debussy, including two copies of the Prélude (see below). His audio cassette collection and library of books contain further recordings, biographies, and critical studies of the composer, alongside works about Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Elgar, Handel, Mozart, and Stravinsky.

Burgess’s early musical ambitions were thwarted when he failed to be accepted to read music at Manchester University, but his love of music remained and would surface in many of his novels, both in their form and in their characters. In A Clockwork Orange (1962), the protagonist Alex is, like Burgess, a lover of classical music. Although Debussy isn’t mentioned explicitly as one of Alex’s favourite composers, it’s likely, as Paul Phillips notes in A Clockwork Counterpoint: The Music and Literature of Anthony Burgess, that Burgess had Debussy in mind when Alex refers to ‘a very nice malenky string quartet, my brothers, by Claudius Birdman.’ ‘Claudius Birdman’ is one of several fictional composers and compositions within the novel.

Similarly, the bliss Alex feels when hearing a new violin concerto by Geoffrey Plautus recalls Burgess’s own transformative experience of listening to Debussy:

Oh it was gorgeousness and gorgeosity made flesh. The trombones crunched redgold under my bed, and behind my gulliver the trumpets three-wise silverflamed, and there by the door the timps rolling through my guts and out again crunched like candy thunder. Oh, it was wonder of wonders.