A Clockwork Orange

A Clockwork Orange is Anthony Burgess’s most famous novel and its impact on literary, musical and visual culture has been extensive. The novel is concerned with the conflict between the individual and the state, the punishment of young criminals, and the possibility or otherwise of redemption. The linguistic originality of the book, and the moral questions it raises, are as relevant now as they ever were.

- A Clockwork Orange

- A Clockwork Orange on film

- A Clockwork Orange on stage

- The Music of A Clockwork Orange

- A Clockwork Orange and Nadsat

- A Clockwork Orange and the Critics

- The Legacy of A Clockwork Orange

- The Podcast

A Clockwork Orange:

‘What’s it going to be then, eh?’ — Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange (1962).

A Clockwork Orange is Anthony Burgess’s most famous novel and its impact on literary, musical and visual culture has been extensive. The novel is concerned with the conflict between the individual and the state, the punishment of young criminals, and the possibility or otherwise of redemption. The linguistic originality of the book, and the moral questions it raises, are as relevant now as they ever were. This resource aims to explore the relevance of A Clockwork Orange, and present valuable information from the archive to anyone interested in learning more about the text. It draws on the collections of the International Anthony Burgess Foundation, delving into the archives and harnessing different media to tell the story of the novel and its legacy.

With its prophetic mixture of drugs, music, fashion and juvenile violence, Burgess’s novel developed a countercultural following in the 1960s. Yet A Clockwork Orange did not reach a mass audience until Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation was released in January 1972. Later on, Burgess sought to distance himself from Kubrick’s ‘highly coloured and explicit’ film and expressed frustration that he would be remembered for this ‘very minor work’, when there were other novels that he valued more highly. Yet he never stopped writing about the book, giving interviews about it, defending it, sometimes disowning it. A Clockwork Orange continued to tick away in Burgess’s imagination until the end of his life.

Burgess began writing the novel in early 1961. He returned to England from colonial teaching posts in Malaya and Brunei in 1959 and noticed that England had changed while he had been abroad. A new youth culture was beginning to appear, with pop music, milk bars, drugs and Teddy Boy violence. Burgess was interested by this emergence of a world that had not existed in his own youth, and he anticipated the arrival of Mods and Rockers when he presented Alex and his droogs as a gang with a tribal fashion sense and a predilection for motiveless violence. This violence, so brutally rendered in the novel, could have been inspired by an incident from Burgess’s own experience. He claimed that the kernel for Alex’s brutal behaviour lay in an attack suffered by his first wife Llewela (Lynne) Jones. During the wartime blackout of 1944 London, Lynne was beaten up and robbed by a gang of American soldiers. A similar attack happens in the novel, when a writer’s wife is beaten and raped by Alex and his droogs.

Despite this, much of Burgess’s inspiration for the novel lay in literature. The dystopian writings of George Orwell (Nineteen Eighty-Four), Aldous Huxley (Brave New World Revisited), Diana and Meir Gillon (The Unsleep) and Yevgeny Zamyatin (We) all provide literary context for A Clockwork Orange. Burgess wrote of his fascination with ‘the ultimate totalitarian nightmare’ as well as ‘the dream of liberalism going mad’. This reading of other novels, coupled with Burgess’s response to the determinism of psychologists such as B.F. Skinner (who denied the importance of culture, environment and free will) provide the background to the book described by Time magazine as ‘that rare thing in English letters: a philosophical novel’.

A working holiday in Leningrad in 1961, for which Burgess learned basic Russian, provided A Clockwork Orange with its most striking feature: ‘Nadsat’ — Russian for ‘teen’ — an invented slang in which the narrator tells his story of crime and punishment. As well as Russian words, Nadsat uses rhyming slang (both real and invented), thieves’ slang, and a few Romany words and phrases. According to Burgess, the Nadsat language ‘was meant to turn A Clockwork Orange into a brainwashing primer. You should read the book and at the end you should find yourself in possession of a minimal Russian vocabulary — without effort, with surprise’. Yet, these exotic sources for the language of the novel obscure an influence closer to home. A 1973 recording of Burgess reading from the novel reveals that the narration is also inspired by the Manchester voices he heard growing up on the streets of the Harpurhey and Moss Side areas of the city.

The title of the novel, A Clockwork Orange, derived from, Burgess claimed, ‘ a phrase which I heard many years ago and so fell in love with, I wanted to use it [as] the title of the book. But the phrase itself I did not make up. The phrase “as queer as a clockwork orange” is good old East London slang and it didn’t seem necessary to explain it. Now, obviously, I have to give it an extra meaning. I’ve implied an extra dimension. I’ve implied a junction of the organic, the lively, the sweet — in other words, life, the orange — and the mechanical, the cold, the disciplined. I’ve brought them together in a kind of oxymoron’. Like many of Burgess’s proclamations, this origin of ‘clockwork orange’ is rather hard to back up. It is not recorded in any dictionaries of London slang, and some linguists believe that the phrase originated in Liverpool. It is apparent that there are no recorded citations of the phrase before the novel was published in 1962, and the only authority for its usage is Burgess himself. It is possible that Burgess is misremembering the genuine Cockney phrase ‘All Lombard Street to a china orange’, or that he simply made it up.

An examination of Burgess’s typescript reveals that he was always uncertain about how the novel should end. At the end of Part 3, Chapter 6, he wrote: ‘Should we end here? An optional “epilogue” follows’. The final chapter of the book is redemptive, with Alex growing up and renouncing violence of his own accord. The penultimate chapter, which is used to conclude the American edition of the book and Kubrick’s film, has Alex returning to his life of crime with evident pleasure.

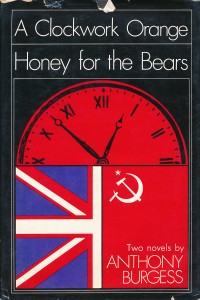

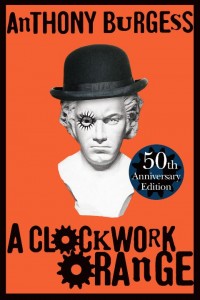

On publication in 1962, A Clockwork Orange sold poorly, with most reviewers baffled by Burgess’s linguistic inventiveness, and disturbed by its violence. However, it quickly became an underground hit, and was adapted by Andy Warhol for his Factory film Vinyl (1965). It did not reach a global audience, however, until its second film adaptation by Stanley Kubrick. Despite being over half a century old, A Clockwork Orange has continued to live on as an important cultural work. After several unofficial stage productions, Burgess wrote his own dramatic adaptation, A Clockwork Orange: A Play With Music, which continues to be interpreted by theatrical companies all over the world. In 2012, Burgess’s song cycle received its European premiere performance at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation in Manchester. To mark its fiftieth anniversary, William Heinemann published A Clockwork Orange: The Restored Edition, with notes, a glossary and previously unpublished essays and pages from the typescript. The novel has also inspired other artists, from musicians and novelists, and has influenced television and film, from Bart Simpson’s Halloween costume to Heath Ledger’s portrayal of the Joker in The Dark Knight.

A Clockwork Orange has variously been described as ‘a nasty little shocker’ (Time), ‘an inventive primer in total violence, a savage satire on the distortions of the single and collective minds’ (New York Times), ‘a terrifying and marvellous book’ (Roald Dahl) and ‘a fine farrago of outrageousness’ (Kingsley Amis). The novel is sure to live on as a classic of twentieth-century literature.