A Clockwork Orange

A Clockwork Orange is Anthony Burgess’s most famous novel and its impact on literary, musical and visual culture has been extensive. The novel is concerned with the conflict between the individual and the state, the punishment of young criminals, and the possibility or otherwise of redemption. The linguistic originality of the book, and the moral questions it raises, are as relevant now as they ever were.

- A Clockwork Orange

- A Clockwork Orange on film

- A Clockwork Orange on stage

- The Music of A Clockwork Orange

- A Clockwork Orange and Nadsat

- A Clockwork Orange and the Critics

- The Legacy of A Clockwork Orange

- The Podcast

A Clockwork Orange on film:

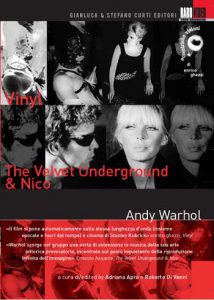

In 1965, the artist Andy Warhol filmed an adaptation of A Clockwork Orange which prefigured Stanley Kubrick’s more famous film by six years, although it is not widely known to mainstream audiences, as it was never released in cinemas. Warhol’s film Vinyl is such a loose adaptation of the source novel that even people who have seen it might be forgiven for not realising that it is built on Burgess’s literary scaffolding. The film is presented as a series of images of brutality, beatings, torture and masochism, all performed by a group of men under the gaze of a glamorous woman. In its preoccupations with pornography and violence, it bears many of the oblique hallmarks of Warhol’s work, along with a familiar cast of Factory regulars, such as Gerard Malanga, Edie Sedgwick and Ondine. The film is disturbing, containing scenes of torture and violence, and it tries hard not to be audience-friendly.

There is a persistent rumour that Warhol bought the film rights of the novel for $3000, yet there is no record of this transaction in the files, and Burgess’s later contract with the producers of Kubrick’s version states that the rights are available. It is likely that A Clockwork Orange was passed around the Factory, and that Warhol, along with the writer Ronald Tavel, decided to make a low-budget pirate after being inspired by the thematic connections between Burgess’s novel and their own artistic work.

It was some years before Stanley Kubrick brought A Clockwork Orange to the cinema screen and a wider audience. Before Warhol, there had been previous attempts to film the novel. A screenplays had been written by Terry Southern and Michael Cooper, while both The Beatles and The Rolling Stones were rumoured to have been cast as Alex and the droogs at various times in the 1960s. It was reported in the press that the director Nicolas Roeg (famous for the films Performance, The Man Who Fell to Earth and Don’t Look Now) would film Burgess’s version of the script, and Kubrick became interested after this production had fallen apart.

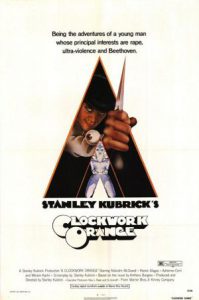

Kubrick first got hold of A Clockwork Orange in 1969 from Terry Southern, who had written some dialogue for Doctor Strangelove. After the mid-1960s there was a new fashion for ‘X-rated’ films containing scenes of sex and violence, and films which depicted gangs of juvenile delinquents. The box-office success of films such as Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971) and Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971) reflected a changing public appetite for dark and violent films. By 1970, Kubrick had directed a string of successful films: Spartacus (1960), Lolita (1962), Dr Strangelove (1964) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). His script draws heavily on Burgess’s original dialogue in English and Nadsat, although the invented language is reduced in the adaptation. The film was shot on location in and around London, and it cost approximately $2 million. It was released in New York in December 1971 and in London a month later, easily recouping Warner Brothers’ original investment by grossing around $40 million worldwide.

Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange is an artful dark comedy of violence, and Malcolm McDowell’s bravura performance as Alex lives large in the collective imagination; but the dazzling colours and fast-paced nature of the film did not appeal to everyone. Pauline Kael of the New Yorker described her unease at the ‘gloating close-ups, bright, hard-edge, third-degree lighting, and abnormally loud voices’, but it is arguably a film designed to disturb its audience. Kubrick encouraged viewers to imagine the garish effects, fillying and tolchocking, and dizzying camera work as a form of dream — a manifestation of the repressed desires and primitive urges that lurk in the minds of all humans. He observed:

‘There may be an argument in support of saying that any kind of violence in films, in fact, serves a useful social purpose by allowing people a means of vicariously freeing themselves from the pent up, aggressive emotions which are better expressed in dreams, or in the dreamlike state of watching a film’.

Despite Kubrick’s artistic intentions, the film depicts the violent scenes with brutality, and it rapidly attracted controversy, with typical headlines including ‘Coming Shortly, a Film for None of the Family’, ‘What Good Can This Film Possibly Do?’, and ‘Garbage Disguised as Art is Still Garbage’. Tabloid journalists claimed that the film had been responsible for a number of ‘copycat’ crimes including home invasions, rapes, street beatings and murder. Headlines such as ‘Hunt for Clockwork Orange Sex Gang’ began to appear in the press in 1972.

Burgess reviewed the film enthusiastically on its release in the Listener, and he established a friendly creative relationship with Kubrick after the film’s release. The director spoke to Burgess about his plans for a film about the life of Napoleon Bonaparte, a project that was never completed, although Burgess used this idea in his novel Napoleon Symphony (1974). In recent years there has been talk of converting Kubrick’s Napoleon script into a mini-series for HBO.

Although he remained on fairly amicable terms with Kubrick, Burgess was infuriated by the publication of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, an illustrated version of the screenplay. Burgess viewed this as an appropriation of his work and reviewed the book unfavourably in the Library Journal. During this time, he became frustrated at journalists who ignored his other novels and asked him to defend the film in the place of the reclusive Kubrick, who left Burgess and McDowell to face the press while he remained in the shadows.

Because of the media controversy surrounding the film — and due to death threats made against his family — Kubrick instructed Warner Brothers to ban all screenings of the film in the United Kingdom. The film remained out of circulation from 1976 until Kubrick’s death in 1999, adding to its cult appeal and causing British viewers to seek out bootleg VHS copies from mainland Europe. Since the film’s official re-release in 2000, no further violent incidents have been reported.