Dystopian Fiction

This resource places Anthony Burgess’s writing in the context of the other dystopian novels of the period.

- Dystopian Fiction

- Dystopias: Burgess’s Introduction to The Aerodrome by Rex Warner

- Dystopias: Burgess’s Favourite Dystopias

- Dystopias: An Extract from The Novel Now

- Dystopias: The Wanting Seed and the politics of fertility

- Dystopias: Burgess and George Orwell

- Dystopias: Burgess and Aldous Huxley

Dystopian Fiction:

The term ‘utopia’, literally meaning ‘no place’, was coined by Thomas More in his book of the same title. Utopia (1516) describes a fictional island in the Atlantic ocean and is a satire on the state of England. The English philosopher John Stuart Mill coined ‘Dystopia’, meaning ‘bad place’, in 1868 as he was denouncing the government’s Irish land policy. He was inspired by More’s writing on utopia.

Dystopian fiction of the twentieth century has its beginnings in the utopian fiction of authors such as H.G. Wells and William Morris. Wells called himself a ‘utopiographer’ and believed that scientific advancements would outlaw war and poverty, as he proposed in his novel, Men Like Gods (1923). This utopian ideal was also described in Morris, who wrote about the perfect socialist society in News From Nowhere (1890). This novel, similar in form to Wells’s The Time Machine (1895), tells the story of William Guest, a nineteenth-century socialist who falls asleep and wakes up in a utopian future society based on common ownership and idealistic tenets such as small non-urban communities, no state authority, no system of monetary exchange, and no class system. In showing a perfect future society, Morris is defending what he believed to be the only way to live without divisions between art, life and work, but also criticising elements of state socialism.

As the twentieth century progressed, authors were less convinced about these notions of scientific and political improvement. Aldous Huxley, in his novel Brave New World (1932), criticised the utopian values of science and the political thinking of novelists such as Wells and Morris. Brave New World is set in a future society, and challenges Wells’s idea that scientific advancement will improve every aspect of life. In Huxley’s vision, children are artificially bred in test tubes, and are content to accept whatever the domineering State bestows on them. The class system in this future world is based on intelligence: the ‘Alphas’ undertaking jobs that require brains, the ‘Deltas’ undertaking more menial tasks. Scientific advances mean there is no crime, and sex is a recreational activity without moral consequences. The hero, John, has been born in a natural way and brought up among ‘savages’ (as they are labelled), outside the dominant society. It is through this character that Huxley criticises the notion of the conditioned subject. The book proposes that a man ceases to be a man when he is incapable of squalor, shame, guilt and suffering. The utopian society appears to be a cage from John’s perspective.

Many dystopian fictions were inspired an earlier Russian novel which examines a futuristic utopia. We by E.I. Zamyatin was published in English in 1924. The plot is similar to Huxley’s novel: the individualistic hero confronts a homogenised state. George Orwell noticed the debt that Brave New World owes to We in his article about Zamyatin’s novel:

‘Both books deal with the rebellion of the primitive human spirit against a rationalised, mechanised, painless world, and both stories are supposed to take place about six hundred years hence. The atmosphere of the two books is similar, and it is roughly speaking the same kind of society that is being described, though Huxley’s book shows less political awareness and is more influenced by recent biological and psychological theories.’

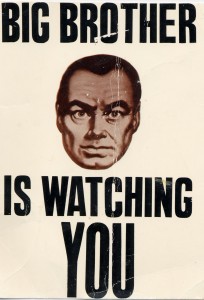

Writers of the 1940s and 1950s were less interested in depicting utopian societies founded on scientific advancements. The form of political dystopia, perhaps inspired by the tumult of the Second World War, began to flourish. Novels such as Rex Warner’s The Aerodrome (1941) and George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) were about societies run by totalitarian governments and, while set in the future, they reflect anxieties the rising power of fascist and Soviet communist regimes.

Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four is among the best-known dystopias of the twentieth century. The future world has been divided into three super-states, Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia all of which are embroiled in a perpetual war. In Orwell’s future, governments use a manipulative form of language called ‘Newspeak’, which states that ‘War is Peace’ and ‘Freedom in Slavery’. Britain has been designated ‘Airstrip One’ and monitors its citizens on behalf of a Stalinist and possibly non-existent leader, Big Brother. The novel’s main characters, Winston and Julia, are two of the last people to possess any concept of freedom. They make futile attempts to rebel against Big Brother, only to be arrested and ‘rehabilitated’ by the State. Orwell’s novel has inspired many subsequent dystopias, including Anthony Burgess’s 1985 (1978).

In 1958 Aldous Huxley published Brave New World Revisited, a non-fiction reassessment of his most famous novel, in which he revisited many of its scientific themes. His central concern is the erosion of personal freedom. The subjects discussed include overpopulation, propaganda, brainwashing, ‘the Arts of Selling’, morality and education. Huxley’s thinking is influenced by the chaotic politics of the 1950s. He writes: ‘The chapters that follow should be read against a background of thoughts about the Hungarian uprising and its repression, about H-bombs, about the cost of what every nation refers to as “defence”, about those endless columns of uniformed boys, white, black, brown, yellow, marching obediently towards the common grave.’

Brave New World Revisited is an important text in the development of post-war dystopias. From his reading of this text, Anthony Burgess produced two novels that dealt with future worlds where freedoms are challenged: The Wanting Seed and A Clockwork Orange, both published in 1962.

A Clockwork Orange deals with the ideas of brainwashing and state control, as the teenage protagonist is stripped of his freedoms after being jailed for murder. You can find out about A Clockwork Orange in the Burgess Foundation’s online resource.

In The Wanting Seed, Burgess addresses the subject of ‘overpopulation’. Set in a future London which reaches from the south coast to Birmingham, the novel depicts a society in which reproduction is policed by a ‘Ministry of Infertility’ and same-sex relationships are officially preferred by the State. The story follows a history teacher named Tristram Foxe as he witnesses the beginnings of a social and political revolution. With reports of mass famine, people begin turning to cannibalism, which leads to chaos and war. For many modern readers, The Wanting Seed is a ‘difficult’ book, which is perhaps more in tune with the politics and social attitudes of the early 1960s than with our own age. The novel presents Tristram’s wife, Beatrice-Joanna, as an archetypal Earth Mother and sexual dissident, but this is not a book heavily informed by the second wave of European feminist thinking.

Burgess’s dystopias of the 1960s follow the convention of the individual against the monolithic state, taking their inspiration from Huxley and Orwell. Later on, the dystopian novel evolved further. Novels such as High Rise by J.G. Ballard (1975) presented modern, consumerist society as intrinsically dystopian. In Ballard’s novel, the residents of an ultra-modern high-rise apartment block are so isolated from the outside world by their luxurious surroundings that they abandon their sense of society and morality. In 1985, Margaret Atwood published The Handmaid’s Tale, a novel which subverts the conventions of political dystopia to explore feminism, racism, Christian fundamentalism and sexuality. The story outlines a future state in which members of an elite class own ‘handmaids’, unwilling sexual slaves and reproductive vessels. Atwood’s novel is a critique of a dystopian society based on religious fundamentalism and systems of sexual and racial oppression.

Dystopian fiction is not always about the future. As Burgess points out in his critical writing, it is also ‘an allegory of the present.’ For writers of his generation — he was born in 1917 — their writing emerged from experiences of military life, the Second World War and the horrors of the Soviet Union. Later on in the twentieth century, dystopian novels reflected other dominant concerns such as consumerism, social equality, and the changing technological world.

In recent times, dystopian writers have returned to the idea of the conflict between science and the individual. Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go (2005) is set in a boarding school for clones who provide donations of vital organs for ‘normals’, or the regular population. Other dystopias deal with ideas of class and freedom. Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games (2008), a novel for young adults, pitches teenagers against each other in a battle to the death in a futuristic arena, overseen by a social elite. There has also been the development of technological dystopias. Black Mirror, a satirical British television series written by Charlie Brooker, asks ‘how we might live in ten minutes time if we are clumsy’, and shows the possible evil effects of smart phones, reality television and social networking. In more recent novels, there has been an important new wave of feminist dystopias, such as The Power by Naomi Alderman, and ecological dystopias, such as The Wall by John Lanchester. It is clear that the dystopian form is far from exhausted, and that it will continue to flourish in a world of climate emergencies, global pandemics and government-imposed lockdowns.