Burgess Memories: David Lodge

-

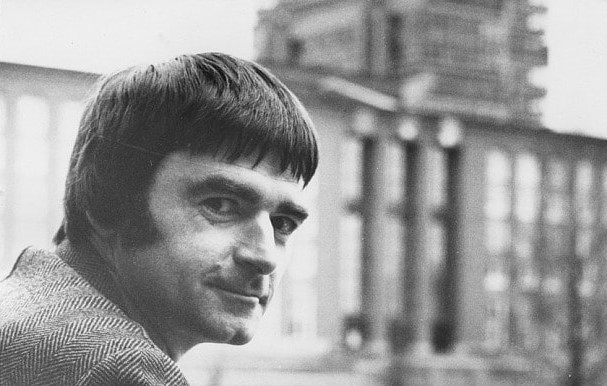

David Lodge

- 17th January 2017

-

category

- Burgess Memories

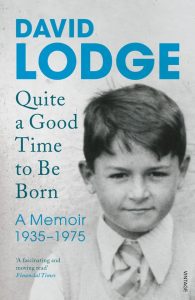

In 1974, when I was a Senior Lecturer in the English Department at Birmingham University, pursuing a twin career as novelist and critic, I was invited by the British Council to do what they called a ‘Specialist Tour’ in Italy, giving lectures at several universities. My itinerary began in Naples and ended in Milan, with a break of a few days in Rome halfway through. The British Council Representative in Rome at the time was Maurice Dodderidge, whom I happened to know slightly because my wife’s family were acquainted with his family in Hertfordshire. Maurice put himself out to make my stay interesting, and introduced me to two British writers then living in or near Rome whose work I knew well and admired: Muriel Spark and Anthony Burgess, Both were Catholics, of very different kinds, and both in their own distinctive styles were important innovators in the form of the novel. This brief account of that first meeting with Burgess, and subsequent contacts with him, is extracted from a second volume of autobiography in progress, sequel to Quite A Good Time to Be Born: A Memoir 1935-1975, published in 2015, which I hope to complete in 2017.

At the time I was in Rome, Anthony was living with his second wife Liana and their son Andrea in Bracciano, an ancient town in the hills about 20 kilometres outside the city, overlooking a picturesque volcanic lake. Maurice kindly drove me there one morning and we spent a pleasant hour or two chatting and drinking on a balcony and enjoying the splendid view. Anthony Burgess was a loquacious host, but I made no notes of the occasion, and all I distinctly remember of what he said was that his reason for moving out of Rome was a fear that his son might be kidnapped. I had reviewed several of his novels over the last ten years, and he had reviewed my second novel, Ginger, You’re Barmy (1962), a circumstance which can cause some awkwardness when writers meet, but there was none in this case. His main criticism of Ginger – that it attributed too much importance to the tribulations of postwar National Service in the army — was entirely understandable coming from a veteran of WW2, and he softened his verdict by predicting a bright future for me as a novelist. My reviews of his novels had been mostly positive, and I could claim some credit for having called Inside Mr Enderby (1963), which he published under the name of Joseph Kell, ‘a little masterpiece’ in the Spectator, without knowing that he was the author. The prolific Burgess adopted this nom de plume when his publishers warned him he would not be taken seriously if he published more than one novel in the same year, and amused himself by writing a favourable review of Inside Mr Enderby for the Yorkshire Post where he was a regular fiction reviewer at the time. Humourlessly they sacked him from this post when the secret of Joseph Kell’s identity was revealed, but he was never short of such employment.

He was an extraordinary writer, a kind of genius, publishing more than thirty novels and as many nonfiction books about literature, linguistics and other subjects, in an unstoppable stream. He made a shortened version of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake with commentary, in a noble effort to coax readers to attempt that formidable text. He wrote poetry, stage plays and screenplays (inventing a language for Stone Age men and women in the French feature film Quest for Fire) and the book and lyrics of a musical version of Cyrano de Bergerac. He was himself a composer of some two hundred and fifty works of music. In 1986 the University gave him an Honorary D.Litt, and I had the pleasure of looking after him during his visit to accept this honour. I found that he always had something knowledgeable to say about the academic specialisation of any member of staff to whom I introduced him, in whatever Department or Faculty. On his last evening a section of the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra gave the first performance of his latest musical composition, a piece for brass ensemble, in the Central Library’s theatre.

I met him occasionally after that in London. The last time was in 1992 when we did a joint event promoting our latest publications in the South Kensington branch of Waterstones – his was a book about the English Language called A Mouthful of Air. He told me privately that he had just been diagnosed with lung cancer and the prognosis was not good. This was not surprising news as he was addicted to cheroots and was defiantly smoking one as he spoke, but it had understandably lowered his spirits. Like the trouper he was, however, he entertained the audience with his usual wit and fluency. He died at the end of the following year.

Perhaps he wrote too much, too fast, and arguably he never produced a flawless masterpiece – even A Clockwork Orange is compromised by having different endings with opposite meanings in the British and American editions – but he made up for his books’ imperfections with the fecundity of his invention, the breadth of his intelligence, and his stylistic virtuosity. It is good to know that there is an International Anthony Burgess Foundation in his home city of Manchester to assert and celebrate his greatness.

Perhaps he wrote too much, too fast, and arguably he never produced a flawless masterpiece – even A Clockwork Orange is compromised by having different endings with opposite meanings in the British and American editions – but he made up for his books’ imperfections with the fecundity of his invention, the breadth of his intelligence, and his stylistic virtuosity. It is good to know that there is an International Anthony Burgess Foundation in his home city of Manchester to assert and celebrate his greatness.

David Lodge CBE is a novelist and literary critic. He is the Honorary Professor of Modern English Literature at the University of Birmingham, where he taught between 1967 and 1987. This piece is an extract from the forthcoming sequel to his autobiography Quite a Good Time to Be Born: A Memoir 1935-1975 which was published in 2015.