Burgess Memories: Desmond Morris

-

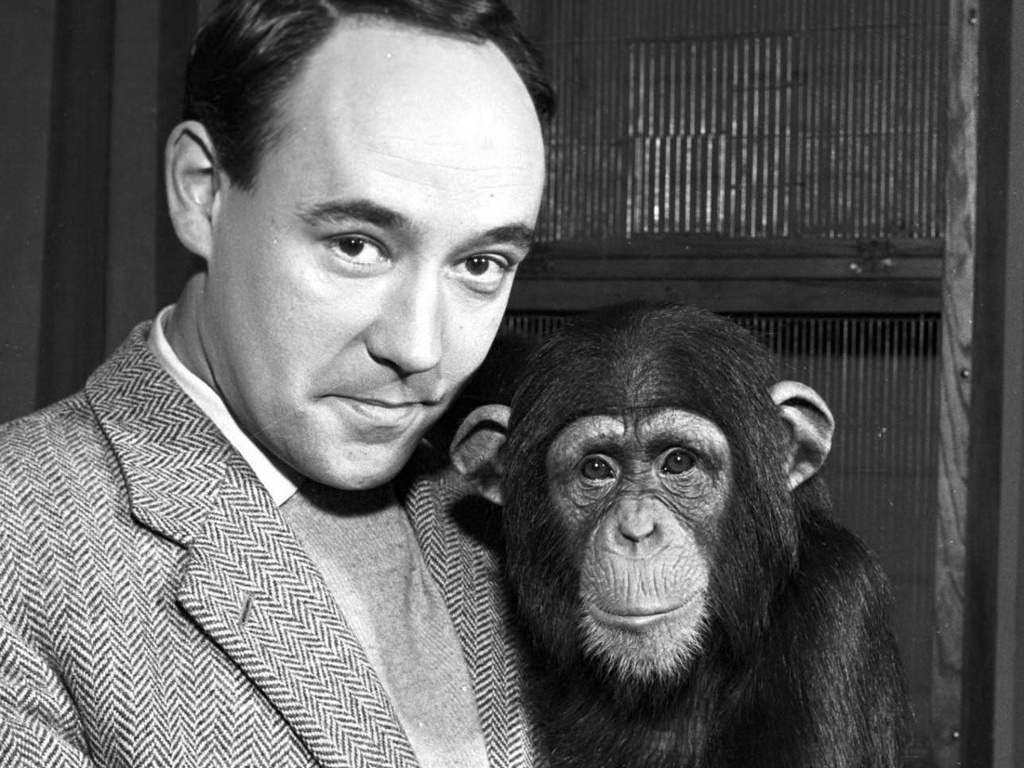

Desmond Morris

- 16th February 2017

-

category

- Burgess Memories

One of my favourite authors, the delightfully chaotic Anthony Burgess, bought a splendid old house in Lija, the village next to ours. With his lively second wife and their small son, he had now moved to Malta where, like me, he was enjoying the escape from city pressure. But there was one big difference between us. I was a scientist who looked upon Gonzi and Co., as a baroque entertainment, while he was a good Catholic who took Church matters seriously. As it turned out, he took them much too seriously. When I told him in a light-hearted way about the infamous Banned Book List, he exploded ‘How could they do that! They must be crazy!’

To me, the Banned List was by now no more than an amusing anecdote and I rather enjoyed the fact that my book was inflammatory in both senses of the word. But to Anthony it was scandalous that the Church, his Church, should be behaving in such a draconian way. I had a bad feeling about what might happen. Burgess in full flood was a frightening prospect.

As a good Catholic, albeit a very modern one by Maltese standards, he felt that he could speak to the Maltese people as if he were one of them. He could proudly say ‘we’ when he addressed them as Catholic to Catholic. Big mistake. He decided that he would deliver a major lecture at Malta’s Royal University. Huge mistake. He would tell them a few home truths about their ridiculous censorship restrictions. Enormous mistake.

He expected me to be there to hear him defending my book and demanding that it should be removed from the Banned List. In fact he wanted the Banned List removed altogether. I tried once again to stop him, but it was no use. His brilliant literary and linguistic brain, which as a writer filled me with awe, was matched by an almost laughable unworldliness. He was like a genius child who hadn’t yet learnt the social niceties. Whatever the opposite of street-wise is, he was it. He was library-wise and street-foolish. For me, it was part of his great charm, but for him it was about to prove costly. I declined his invitation to attend the great event and felt myself sinking in his estimation.

He tried to enlist some of the other authors on the island and, in his autobiography he writes: ‘there was not one British resident prepared to join my fight against censorship.’

The day of the lecture arrived. Burgess was a famous figure and the turn-out was impressive. Three hundred Maltese clergy settled down to listen to him in the main lecture theatre of the university. They may have been hoping for a few choice literary gems, but instead they found themselves on the rack. Burgess castigated them at great length for their prudery and for their narrow-mindedness. He berated them for allowing the Maltese people to be treated as children and, reaching his climax, informed them that, unless human adults were allowed to come face to face with every kind of human experience, they would never learn to make up their own minds about what was good and what was bad, and from within themselves to resist the bad. If you treated people like naughty children, they would behave like naughty children. ‘It is no wonder’, he stormed, ‘that when the Maltese emigrate to England they become the brothel-owners of Soho.’

His tirade was met with a stony silence throughout, followed by a politely subdued mass exit. Common courtesy was considered to be a major attribute in these small, heavily populated islands and, despite his best intentions, Burgess’s abrasive remarks were deeply offensive to his cultured audience. He kept saying ‘we’, assuming that his known Catholicism would enable him to treat them as ‘family’, but to them he was a revered visitor, a famous, foreign exotic, and the last thing they expected from him was a public ‘family row’.

From this point on, the Maltese authorities started a vendetta against him. After he returned from some foreign travels he found that his car, a much loved Morgan, had been confiscated. Later, he received an official letter announcing the forthcoming confiscation of his other vehicle, a Bedford Dormobile. Without waiting for this to happen, he and his wife and son found a cargo boat leaving for Naples and secretly drove the Dormobile on to it at dawn.

Before long the Maltese government announced that Burgess was deleted from the list of residents and that it was confiscating his house. He was instructed to hand over the keys. Writing in the New York Times, Burgess ranted that ‘This is a totally vindictive act – a naked confrontation between the state and the individual.’ The international press made a fuss about the confiscation and Burgess records that ‘The house was speedily deconfiscated, but neither its sale, nor its lease was permitted. It was to stand empty and still does.’ That was written twenty years later, in 1990, and as far as I know the house has remained empty to this day – all the result of one ill-advised speech.*

I felt terrible that this had all started from his defence of my book, but I had tried my hardest to warn him off and he had refused to listen.

It is now clear to me why Burgess felt so determined to deliver his unpopular message to the Maltese elite. By imposing a strict censorship on books, the Maltese authorities were robbing their people of the chance to make their own decisions. Better to give them their freedom, even at the cost of exposing them to controversial ideas, rather than stamp out all forms of personal rebellion. It is important to realize that alongside every destructive act of rebellion, there may be dozens of constructive ones, and it is those that give society its innovations and its triumphs.  For a man who claimed that his wife had, in real life, been savagely attacked by young thugs, this was a remarkable assessment. But then Anthony Burgess was a remarkable man.

For a man who claimed that his wife had, in real life, been savagely attacked by young thugs, this was a remarkable assessment. But then Anthony Burgess was a remarkable man.

*Editorial Note: the house was sold by Liana Burgess in the late 1990s.

Desmond Morris is a zoologist, sociobiologist, writer and broadcaster. He wrote the bestselling study of human behaviour, The Naked Ape (1967). This piece is an edited extract from his autobiography Watching (2006) used with permission from the author.