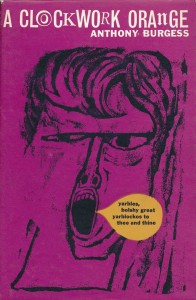

A Clockwork Orange

A Clockwork Orange is Anthony Burgess’s most famous novel and its impact on literary, musical and visual culture has been extensive. The novel is concerned with the conflict between the individual and the state, the punishment of young criminals, and the possibility or otherwise of redemption. The linguistic originality of the book, and the moral questions it raises, are as relevant now as they ever were.

- A Clockwork Orange

- A Clockwork Orange on film

- A Clockwork Orange on stage

- The Music of A Clockwork Orange

- A Clockwork Orange and Nadsat

- A Clockwork Orange and the Critics

- The Legacy of A Clockwork Orange

- The Podcast

A Clockwork Orange and the Critics:

A Clockwork Orange gained mixed reviews on its publication in 1962. Most of the reviews praised the inventiveness of the language, while at the same time stressing unease at the violent subject matter. While The Spectator praised Burgess’s ‘extraordinary technical feat’ it also was uncomfortable with ‘a certain arbitrariness about the plot which is slightly irritating’. New Statesman called the book a ‘great strain to read’, though it praises Burgess for addressing ‘acutely and savagely the tendencies of our time’. The Times Literary Supplement was more critical, accusing Burgess of being ‘content to use a serious social challenge for frivolous purposes, but himself to stay neutral’.

The novel impressed other writers, with Kingsley Amis writing that ‘Mr Burgess has written a fine farrago of outrageousness, one which incidentally suggests a view of juvenile violence I can’t remember having met before’. Malcolm Bradbury reviewed the novel in a more measured fashion, writing ‘All of Mr Burgess’s powers as a comic writer, which are considerable, have gone into the rich language of his inverted Utopia. If you can stomach the horrors, you’ll enjoy the manner’. Roald Dahl simply called it ‘a terrifying and marvellous book’.

In the United States, the reception to the novel was much more positive. The Washington Post praised Burgess’s ‘Joycean’ inventiveness and the brilliance of his writing, while the Berkeley Gazette claimed the novel ‘offers a frightening insight into the probable thinking of the violent young’. American reviewers were not as troubled by the brutality of the novel as were their British counterparts. Tulsa World noted that the ‘story moves along rapidly and keeps you smiling even while heads are being bashed and stomachs kicked’.

When it was first published, the novel was not an instant hit with audiences. The book sold poorly despite the praise other authors had given it. By the mid-1960s A Clockwork Orange had only sold 3872 copies. However, as time passed, the notoriety of the book increased, partly fuelled by Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation. Burgess became what he called ‘a major spokesman on violence’ and was constantly called to defend his book, Kubrick’s film, and to talk about violence in the media. Throughout the 1970s A Clockwork Orange became one of the scapegoats for any crime and violence that befell British society, something which perturbed Burgess. In 1972, he wrote, ‘What hurts me, as also Kubrick, is the allegation made by some viewers and readers of A Clockwork Orange that there is a gratuitous indulgence in the violence which turns an intended homiletic work into a pornographic one’.

Burgess had a complicated relationship with his most famous novel. He writes, ‘I do not like the book as much as others I have written: I have kept it, till recently, in an unopened jar — marmalade, a preserve on a shelf, rather than an orange on a dish’. Yet, it would be overstating it to claim that Burgess actively disliked the book. His attitudes changed at various different points in his life, but he did repeatedly return to A Clockwork Orange, turning into a stage play, writing articles about it, and even writing a novel based on the production of the film, A Clockwork Testament, or Enderby’s End. The latter calls on Burgess’s eponymous poet to deal with the unwanted fame afforded to him by an adaptation of his screenplay that ‘makes A Clockwork Orange look like Old Yeller’.

The novel continues to be regarded as one of the masterpieces of twentieth century literature, and continues to inspire new generations of readers.