Object of the Week: Burgess Lecturing on Marlowe

-

Graham Foster

- 24th April 2017

-

category

- Object of the Week

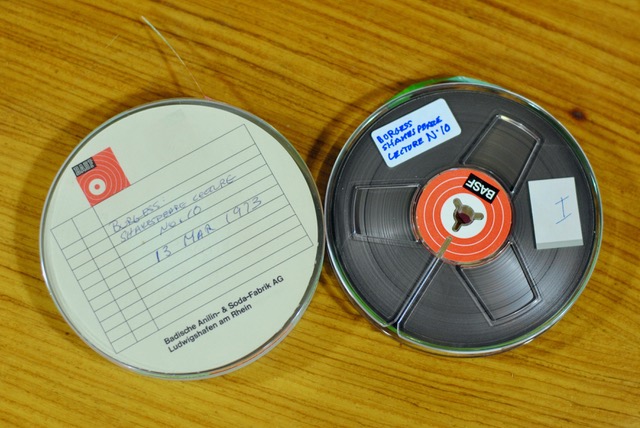

The sound archives at the Burgess Foundation contain thousands of hours of recordings, including Burgess playing music, practicing lectures, reading from his own works, and speaking in public. This audio extract is from a series of lectures Burgess gave at City College in New York about Shakespeare and his peers. This recording was made on a reel-to-reel tape on 13 March 1973, and features Burgess telling the story of Christopher Marlowe’s death, a tragedy he likens to the death of ‘Keats at 26 or Chatterton at 17’.

Burgess was employed at City College as Visiting Professor of English Literature and Creative Writing between 1972 and 1973. At this time, City College was experimenting with free education, and had opened its doors to anyone who wanted to study there, regardless of formal academic qualification. There was a great variety in the student body, and Burgess ended up teaching students from diverse backgrounds. He taught alongside Joseph Heller, who remembered Burgess as someone who had a ‘desire to teach, to bring about a positive change in what were sometimes rather deranged minds […] I admired the way Burgess could take even the most hostile of these students seriously. He knew and remembered their names. He gave serious thought to even their most absurd statements.’

The lecture extracted here is the tenth in his series about Shakespeare, a weekly course which was ‘given at eight in the morning to two hundred and fifty students.’ Burgess remembers that even at that early hour, he had to compete with the ‘ghetto blasters’ of gangs of students outside the lecture theatre. He writes, ‘I rebuked them and received coarse threats in return, as well as scatological abuse which was unseemly in any circumstances but monstrous when directed at even an undistinguished professor. What would Bertrand Russell have done?’ Russell was Professor of Philosophy at City College in 1940 (before being dismissed as “morally unfit” to teach at the institution).

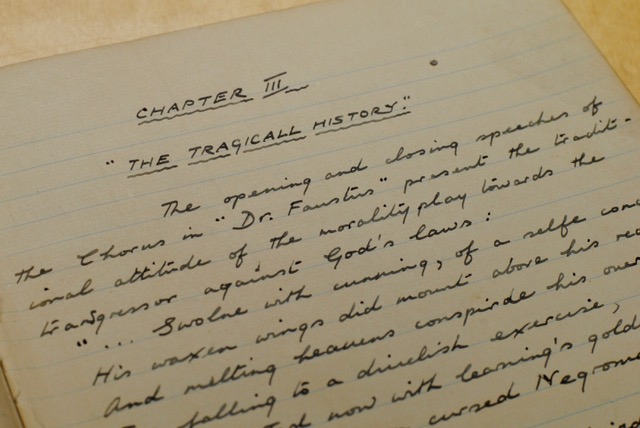

Burgess’s interest in Shakespeare is well known, and he wrote two books: Shakespeare (1970), a biography of the Bard, and Nothing Like the Sun (1964), a novel about Shakespeare’s love life. While Burgess only produced one book about Christopher Marlowe, A Dead Man in Deptford (1993), he wrote his undergraduate dissertation about Marlovian theatre in 1940 (pictured below). Before devoting a novel solely to Marlowe, and both his stage- and spy-craft, he wrote the playwright into Nothing Like the Sun. Marlowe is a presence in the novel, and is mentioned by other characters, but he never enters the scene in the narrative.

Burgess also wrote about Marlowe in his critical books English Literature: A Survey for Students (1958) and They Wrote in English (1979). In the former, he writes, ‘not even Shakespeare could do all that Marlowe could do: the peculiar power gained from caricature; the piled-up magnificence of language; above all, “Marlowe’s mighty line” – these are great individual achievements. There is nobody like Christopher Marlowe’. In A Dead Man in Deptford, Burgess has Marlowe writing several of Shakespeare’s plays, including Henry VI. Rather than a hard theory about the role of Marlowe in Elizabethan theatre, this is perhaps a rather mischievous joke on Burgess’s part.

This extract from a longer lecture about Elizabethan London, shows Burgess’s knowledge of his subject, and reveals his awareness of the many interpretations of Marlowe’s mysterious murder long before he came to write his novel on the subject. It also shows that Burgess was an engaging and entertaining speaker, a talent he had cultivated during his time as a schoolmaster in Bamber Bridge, Banbury and Malaya. Burgess never lost his desire to teach, and returned to it at various points in his life as a professional writer, lecturing at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Princeton University among other places.

Nevertheless, Burgess’s time at City College was not all happy. His memories of the America of the early 1970s are of a discontented populace and a lack of interest in culture. In an interview with the Evening Standard, published one day after he gave this lecture, he says, ‘Hoarse male voices abuse me on the telephone, telling me to eff off back to effing Russia just because I suggested that America would be better with a national health service.’ These experiences of the United States did not prevent him visiting and working in the country throughout his life.