Object of the Week: Burgess’s Favourite Novels in Translation

-

Graham Foster

- 15th May 2017

-

category

- Object of the Week

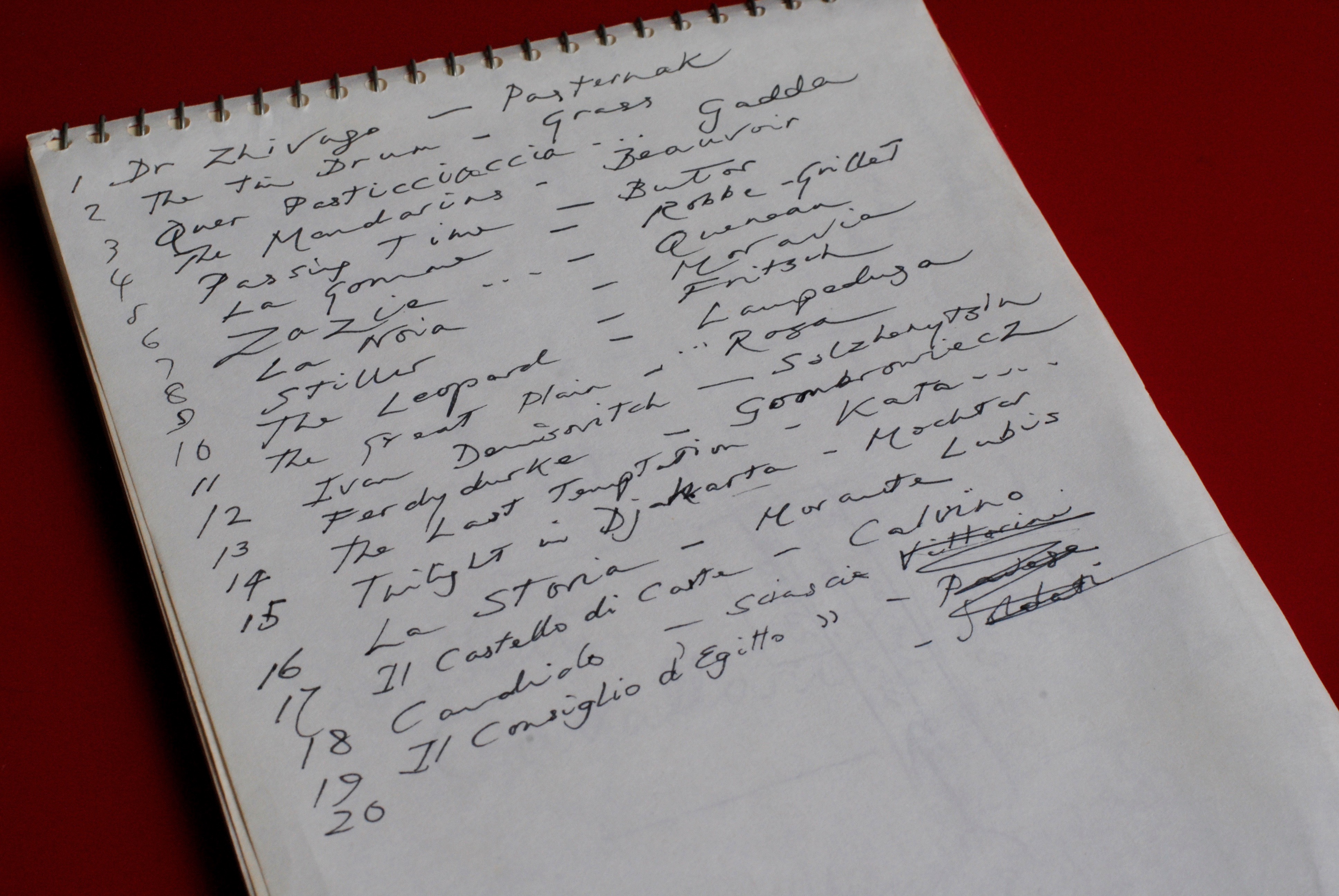

In 1984, Burgess released his book Ninety-Nine Novels: The Best in English Since 1939, a provocative list of his favourite novels in English. A recent discovery in the Burgess Foundation archive is a notebook containing a list of Burgess’s favourite books in translation. Internal evidence suggests that this list dates from the same year as Ninety-Nine Novels, and these may be initial notes towards a companion volume to that book.

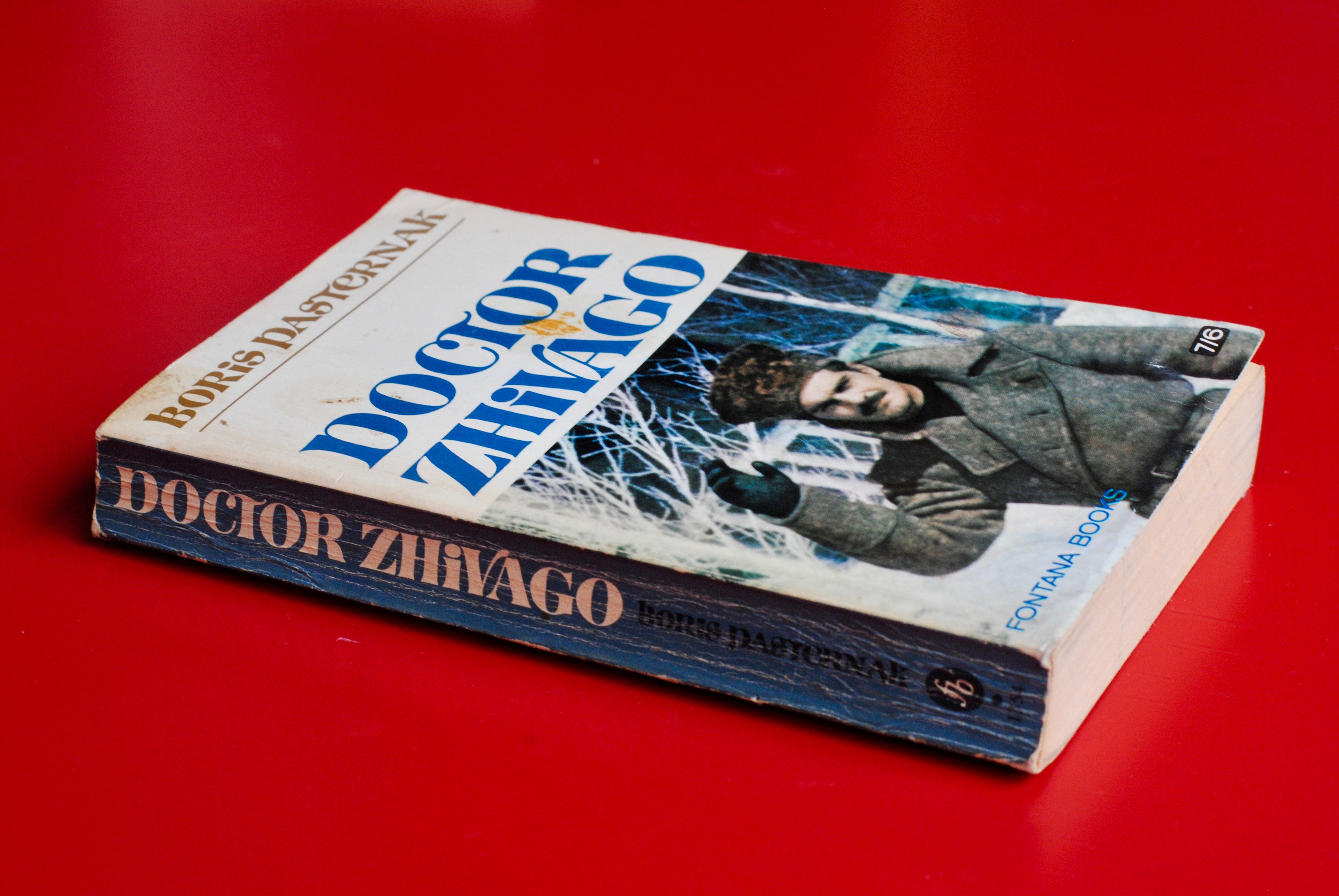

The list consists of nineteen books, the selection of which gives an insight into Burgess’s reading habits. That he would choose Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago (1957) is no surprise. In Honey for the Bears (1963), the novel inspired by his holiday to Leningrad in 1961, Paul Hussey is worried that his copy of Doctor Zhivago will be confiscated by an over-zealous customs officer. Writing in 1990, Burgess remembers: ‘I had my copy of Doctor Zhivago confiscated by customs and, at a ridiculous literary conference, had to hear Pasternak reviled for misrepresenting the October Revolution. But art, I cried, is above politics.’

Similarly, The Tin Drum by Günter Grass (1959) is not a surprising choice. Burgess writes about Grass in several places and states that ‘He has looked at a diseased and convalescent and over-affluent Germany with the eyes of fantasy, that kind termed Rabelaisian, which admits monstrous exaggeration, word-play, mad catalogues, intestinal jokes and noises, allegory, magic, the setting of the historically embarrassing in a context of laughter.’

Burgess lived near Alberto Moravia in Rome during the 1970s. The two writers became friends and, according to Burgess, were described as two of the three most important living novelists by literary broadcaster Bernard Pivot. The third was Günter Grass. When Moravia died in 1990, Burgess wrote his obituary for The Independent.

Some of the books are more unexpected, and there is no surviving writing about them by Burgess. The Leopard by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa (1958) is a novel which shares some Burgessian characteristics such as a historical setting which speaks of the contemporary state of Lampedusa’s native Sicily. Lampedusa wrote as widely as Burgess, and his output includes novels, short stories, and an introduction to sixteenth century French literature. Like Burgess, Lampedusa began begin writing during the Second World War, and he also had a talent for self-invention.

Another interesting choice is Michel Butor’s Passing Time (first published as L’emploi du temps in 1956). The novel is inspired by the period when he was teaching at Manchester University, and describes (not entirely favourably) the city of Burgess’s birth. The novel contains a map of the fictionalised Manchester that blends the real city with the hallucinatory version. Part mystery, part experimental novel, Passing Time has some similarities to Burgess’s own work, such as Any Old Iron (1989), which blends subliminal and cerebral writing with the tropes of more mainstream fiction.

Burgess’s full list of nineteen titles is:

- Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak

- The Tin Drum by Günter Grass

- Quer Pasticciaccio Brutto De Via Merulana (That Awful Mess on Via Merulana) by Carlos Emilio Gadda

- The Mandarins by Simone de Beauvoir

- Passing Time by Michel Butor

- Les Gommes (The Erasers) by Alain Robbe-Grillet

- Zazie dans le Metro (Zazie in the Metro) by Raymond Queneau

- La Noia (Boredom) by Alberto Moravia

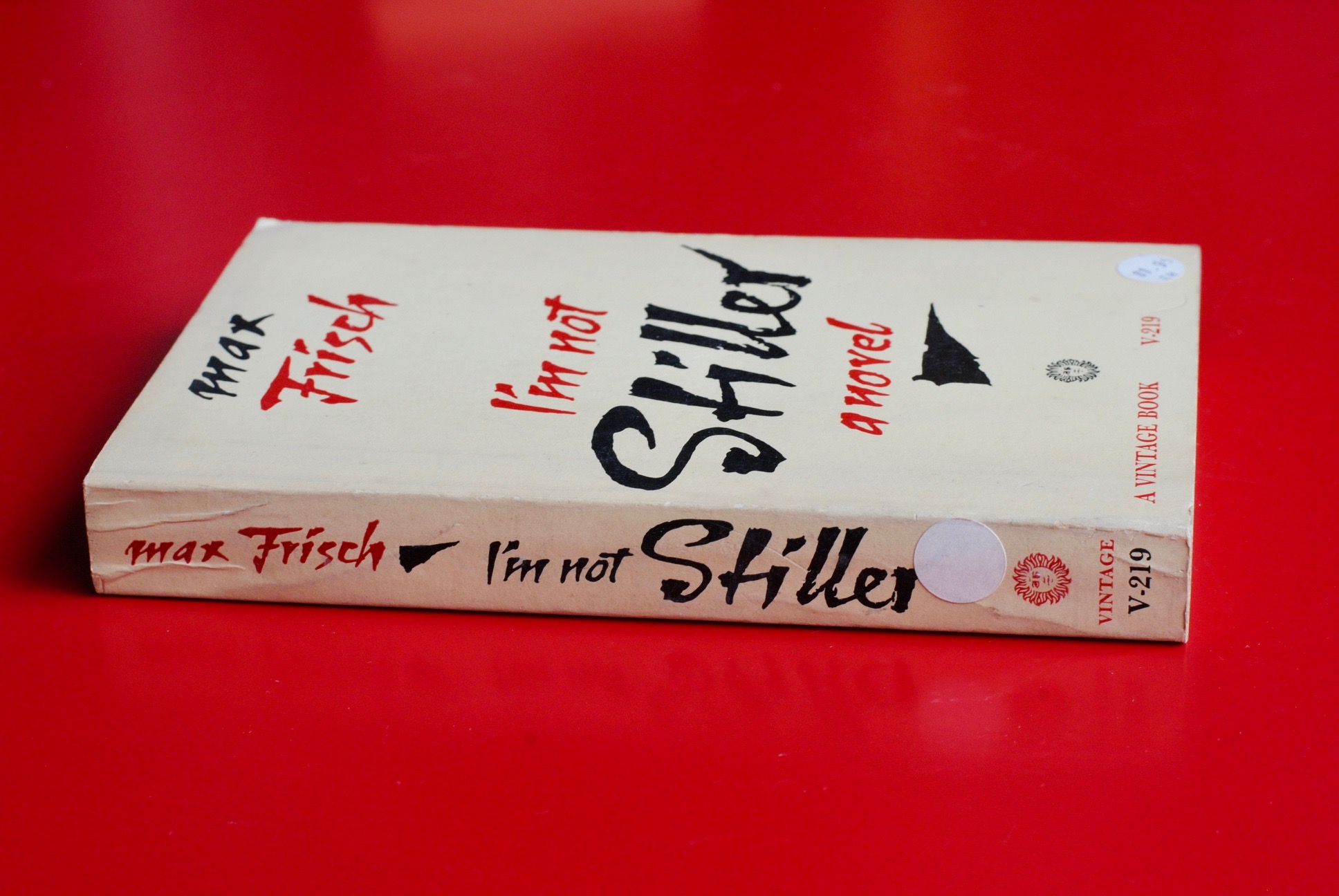

- I’m Not Stiller by Max Frisch

- The Leopard by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa

- The Great Plain by João Guimarães Rosa

- One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

- Ferdydurke by Witold Gombrowicz

- The Last Temptation by Nikos Kazantzakis

- Twilight in Djakarta by Mochtar Lubis

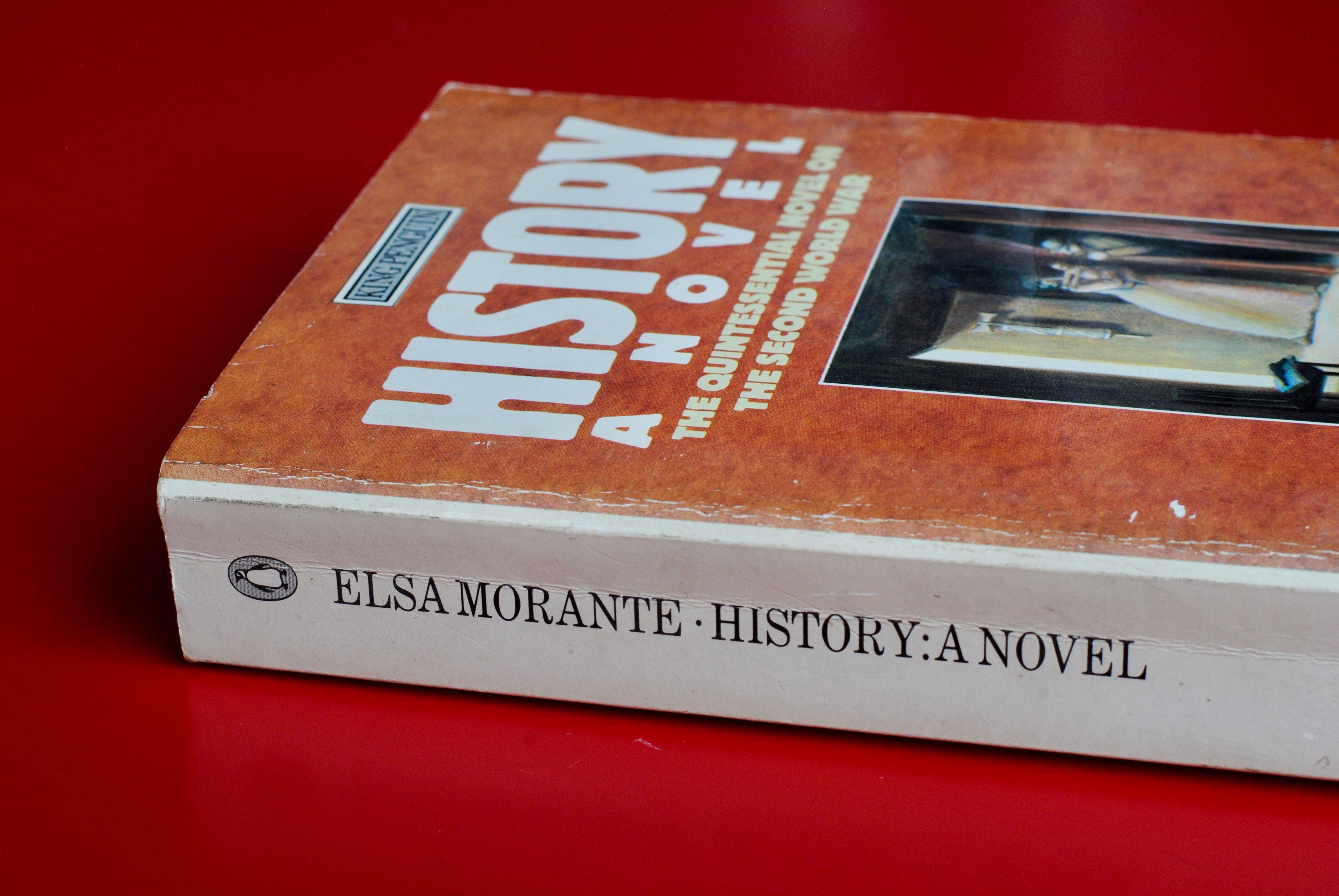

- La Storia (History: A Novel) by Elsa Morante

- Il Castello di Caste [sic] (The Castle of Crossed Destinies) by Italo Calvino

- Candido by Leonardo Sciascia

- Il Consiglio d’Egitto (The Council of Egypt) by Leonardo Sciascia

This list is an important discovery and tells us much about Burgess’s engagement with world literature, and it opens up research opportunities which may provide new insights into his own fiction. Further research may solve a few mysteries on the list. The book that Burgess titles The Great Plain may refer to a novel by João Guimarães Rosa called Grande Sertão: Veredas (1956). This novel was published in England as The Devil to Pay in the Backlands, but Burgess could have read it in another language. He has also mistitled the Italo Calvino novel, the original Italian title being Il Castello dei Destini Incrociati.

Burgess was such a prolific reader that his library offers many research opportunities. The Burgess Foundation has a collection of about 8000 books. Another collection of books is on deposit at the University of Angers.