Burgess Memories: Lorna Sage

-

Lorna Sage

- 25th May 2017

-

category

- Burgess Memories

The most telling memorial to Anthony Burgess would have been to leave a big white gap on the pages of the Observer or the Independent or whatever – the space his words would have filled. His death must supply work for a good handful of aspiring literary journalists, job opportunities galore. And that’s just in the Grub Street corner of the literary A to Z. But did his many roles and his polyphonous oeuvre – novelist, librettist, composer, scriptwriter, reviewer, teacher – add up? Even if you concentrate on the prose, and leave out the lyrics and the music (which, being tone-deaf, I’m obliged to), it’s still hard to decide whether his work is as much as the sum of its parts.

The most telling memorial to Anthony Burgess would have been to leave a big white gap on the pages of the Observer or the Independent or whatever – the space his words would have filled. His death must supply work for a good handful of aspiring literary journalists, job opportunities galore. And that’s just in the Grub Street corner of the literary A to Z. But did his many roles and his polyphonous oeuvre – novelist, librettist, composer, scriptwriter, reviewer, teacher – add up? Even if you concentrate on the prose, and leave out the lyrics and the music (which, being tone-deaf, I’m obliged to), it’s still hard to decide whether his work is as much as the sum of its parts.

It’s the kind of question he had deliberately posed, to himself as well as to his readers, at least from the 1970s on, when instead of settling down and producing books that were densely layered and epically difficult and despairing and very far apart in the manner of (say) Pynchon or Gaddis he started throwing off playful, complex novels – MF (1971), Napoleon Symphony (1974), Beard’s Roman Women (1976), ABBA ABBA (1977), – at such indecently close intervals that they somehow disqualified themselves as canonical texts. Burgess didn’t strike people as post anything because he wasn’t troubled enough. He was too blithely at home with the promiscuous tricks of language. He throve on epistemological anxiety, took it in his stride, and seemed to contradict the founding hypothesis about crisis of signification. Authorship for him was a way of life in more senses than one, and when he took on the fashionable paradoxes – writing as dissemination in Earthly Powers, for instance (paper Onanism, recklessly spending words, echoes of Derrida) – then too his very enjoyment of the task, his ingenuity and irreverence and fluency, told against him.

Joyce was a great hero and mentor, but it’s characteristic that in the second part of his autobiography, You’ve Had Your Time in 1990, thinking about what the life of letters really meant to him, he questioned even that allegiance, and bracketed Joyce with Woolf (very much not his favourite modernist). ‘Here I lay myself open to charges of middlebrowism. But probably the novel is a middlebrow form and both Joyce and Virginia Woolf were on the wrong track.’ Wordplay, self-consciousness, polyglot punning AB enjoyed beyond measure, but at the same time he liked to combine these signs of Literature with a capital L, literature squared, with a no-nonsense approach derived from Grub Street mores. He disapproved of Joyce for being a scrounger, he thought you could and should produce great art for money, in the style of Herman Wouk or – let’s not be modest – Shakespeare, or Mozart. He admired Mozart for being ‘prolific’, ‘a serious craftsman and a breadwinner’, as he said in his bicentennial tribute-cum-travesty, Mozart and the Wolf Gang. Bloomsbury gentility and ‘costiveness’ (Forster was the prize example) could be relied on to provoke his scorn for several reasons at once therefore: mystificatory reverence for Art, snobbish resentment of one’s audience, and a kind of stinginess with one’s talent which he seems Freudianly to have associated with anal retentiveness.

By contrast – though retaining the same metaphor – he was unashamed of his own logorrhoea. Pressed to explain why he wrote so much, he developed over time a number of motives. The first and most famous is the diagnosis of an inoperable brain tumour in 1959, when John Wilson was given a year to live at the most, and as a result became Anthony Burgess full-time in order to earn royalties for his prospective widow, as he put it. ‘I was not able to achieve more than five and a half novels of very moderate size in the pseudo terminal year. Still, it was very nearly E.M. Forster’s long life’s output.’ It’s a chillingly good story, and seems to be true, though it doesn’t explain why he went on going on at such a lick once the misdiagnosis was discovered.

In fact, the reprieve hardly slowed him down at all, whereupon he produced a second strand of explanation which had to do with the childlessness of his first marriage to Lynne. Perhaps it was, he suggests, a matter of books substituting for babies – ‘I had converted what I termed paternity lust into art.’ This may sound an implausibly Platonic theory, but George Steiner gave it a convincing run for its money not long ago in Real Presences, and Burgess himself in Earthly Powers had lent it an extra colour of likelihood by making his compulsive writer-hero homosexual. Except that by the date of Earthly Powers (1980) he wasn’t childless any longer. When Lynne died in 1968, there was a new wife-to-be, Liana, plus their son (of whose birth he had been unaware) waiting in the wings. But this meant, of course, that now he had a wife and child to support…

All of which suggests that he didn’t quite know why his writing was so compulsive. It was as though the words wrote him. While other literary folk were addicted to alcohol, or sex, or drugs, he was so innocently fixated on his profession. Here the book-reviewing came in handy – to fill the gaps between books – and also the scriptwriting. Gore Vidal recalls that he more than once passed on to Burgess lucrative jobs in that line, which were snapped up and dispatched with alacrity. The relationship between the two of them is perhaps more of a clue to ‘placing’ Burgess than this venal tie suggests. For though Vidal exercises more quality control, and separates out his different kinds of writing more – so that, for instance, the histories are done in lucid, ironic, discursive style, while the satires are lusciously vile, masterpieces of inverted decorum – they both belong to the tradition of carnivalesque adventurers, the breed of writer who according to the school of Bakhtin) follows on from Petronus, Apuleius, Rabelais and Sterne. This kind of serio-comic writing is made up of parodies of the straight kinds. It was (says Bakhtin) ‘the “journalistic” genre of antiquity … full of overt and hidden polemics with various philosophical, religious, ideological and scientific schools … seeking to unravel and evaluate the general spirit and direction of evolving contemporary life.’ This comes from the book on Dostoevsky’s Poetics, so it has to be slightly edited to fit, but it does fit rather well, since it gets the sense of epic ambition, along with mock-epic tactics like (another good phrase) ‘slum naturalism’.

So a ragbag of a book like The End of the World News in 1982 – a tripartite travesty, made up of a drama-doc about Freud, a libretto for a musical about Trotsky, and a sci-fi ‘or futfic’ story about the end of culture as we know it – does have a genre after all. Burgess suggests as much when he complains in the autobiography that ‘That term “ragbag” is always turning up, usually when my work is at its most structured.’ He wasn’t thinking of Bakhtin, but of structuralism and Lévi-Strauss, but in a general way the notion of programmed mayhem, or self-conscious surface disorder with an underlying pattern, can be accommodated to the carnival idea. Music, he liked to say, can aspire to universality (‘Music is the Armagnac of the saved. The musician alone has access to God’), whereas the art of words, by contrast, are local, referential, impure: ‘to deal in pure structure is a huge relief from peddling those impure structures called linguistic statements’. Literature is in league with imperfection, and even within the Babel-world of literature, there are those who understand that comedy has the last word (like Cervantes) and those who (like Shakespeare) hanker after the glamour of tragedy. Just as he loved Joyce this side idolatry, so he adored Shakespeare but found him less myriad minded than he’s cracked up to be. That Shakespeare is the national bard had something to do with it: Burgess was all for crossing frontiers and cross-breeding cultures, an Esperantist of the spirit.

Burgess does, then, ‘make sense’, he has a poetics. And yet there remains something resistant and idiosyncratic about his work which even the right anti-tradition can’t quite accommodate. You can line him up with the correct contemporary attitudes, but there’s something left over, something anachronistic about his postmodern-seeming stress on the arbitrary, shifting and ephemeral nature of words. It’s as though he is trying to turn writing back into the condition of speech and set up a dialogue with his readers, a running commentary almost as continuous as breathing. This means that he doesn’t go in for the double-think which finds a surreptitious sublimity in the very recognition that Literature is discredited. By the sheer quantity and continuity of his writing, he produced a real sense of the limits of what words can do. He lived that wry comedy (not a tragedy at all) and acted it out.

This involves a very special kind of modesty which almost amounts to the opposite (the devil’s mode, he called it in one book) – a modesty which despises those who take themselves too seriously. Look, he’s saying, I can do it just as well as you if not better, any old time, week in week out, without trying to set it in stone. This in the end, I’m sure, was why he liked literary journalism so much: the proud debasement of Grub Street, the place where you know exactly what your words are worth. So he wrote all the hours God gave. He hoped, perhaps, that if in this curious way he kept his head down, the Almighty might look the other way, and Art would creep in at the back door. If you identify writing with living so closely, you don’t want to produce something too finished – after all, time will do that for you.

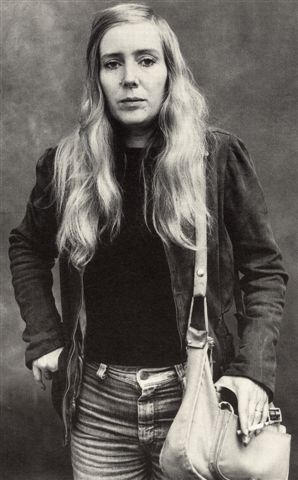

Lorna Sage was an academic and literary critic. She wrote studies of Doris Lessing and Angela Carter, and was Professor of English Literature at the University of East Anglia. She won the Whitbread Biography Award for her memoir Bad Blood (2000). Sage died in 2001. This piece was originally published in the Times Literary Supplement in 1993 and is reproduced with kind permission from the Estate of Lorna Sage.