Burgess Memories: Stanley Silverman

-

Stanley Silverman

- 1st June 2017

-

category

- Burgess Memories

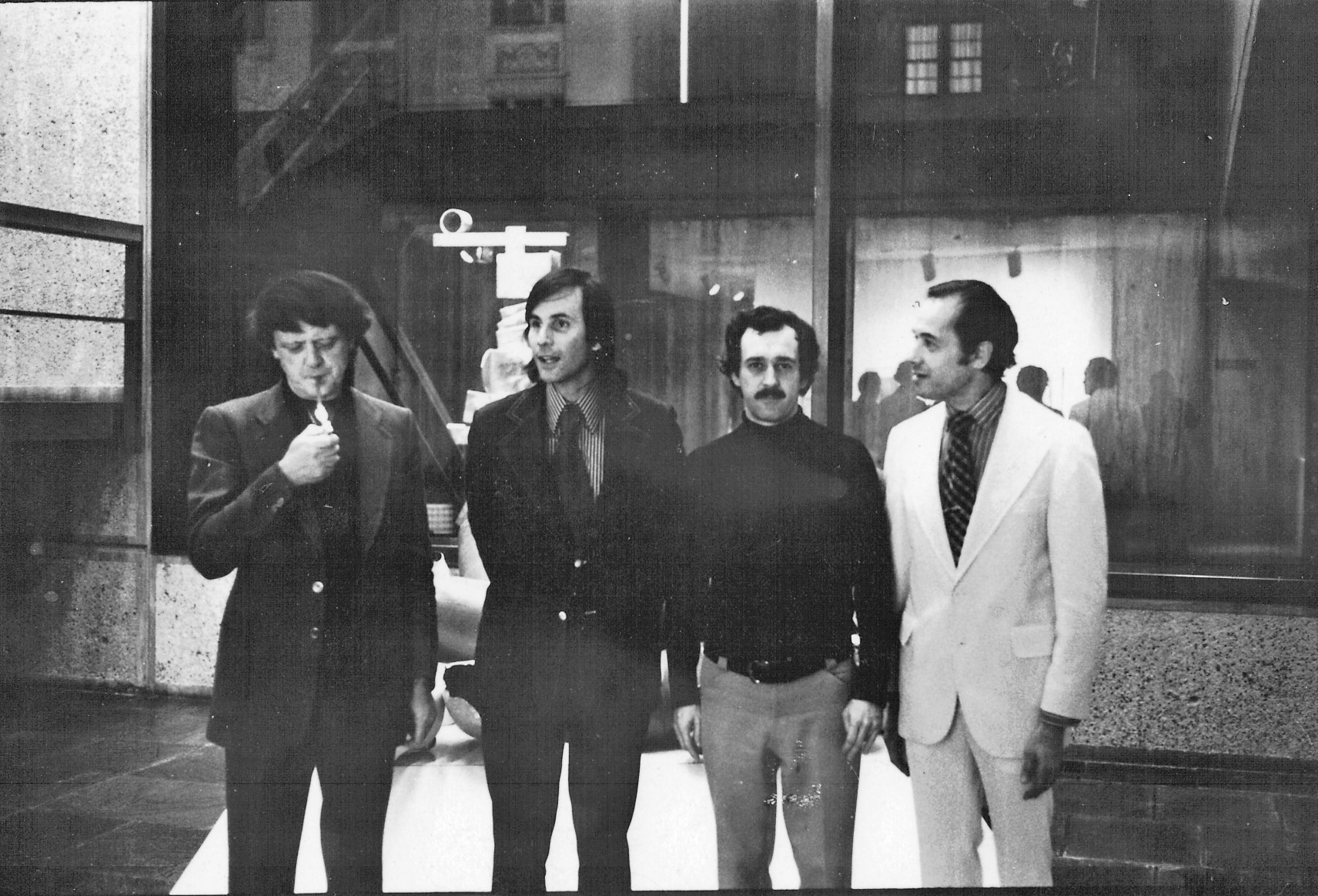

Anthony Burgess was wonderful, extraordinary, kind of a good-looking guy, you know, tall, straight, chain smoker of these little cigarillos. He’s a great man now and everyone takes him seriously, but he was a lot of fun and especially with the wives we had a lot of good times.

Anthony Burgess was wonderful, extraordinary, kind of a good-looking guy, you know, tall, straight, chain smoker of these little cigarillos. He’s a great man now and everyone takes him seriously, but he was a lot of fun and especially with the wives we had a lot of good times.

He talked about music a lot to me, and there was the underlying dispute because my background’s mostly in atonal art music, the kind of post-War stuff like Webern, Boulez, Stockhausen, and he just didn’t like that. He was very much of the old-time stuff: Holst, Elgar, tonal music. His quote was, ‘You can’t express joy in atonality’.

Burgess’s own music was of the British mould, of the pre-avant garde, I’d say pre-Second World War. It was very tonal, very well constructed, and dramatically constructed too. He knew about fast endings. He used to drive me nuts about that because I never particularly thought about those things. He’d say ‘You’ve got to add a minute of fast at the end for the audience.’ That was really his thing. He had a facility for instruments too, he knew instruments. Very strange ones too. There’s a guitar quartet he wrote.

He was teaching at Princeton, so he was around in the United States in the early 1970s a lot. We were always socially pretty close. Especially with Liana because the families were friendly and they had a son the age of my step-daughter. So I’d see a lot of him and we discussed the world in general. At that time it was the beginning of the rise of various assassinations. It was a bad time, the early Seventies. There were planes going down. There was a lot to talk about.

When he wrote prose, which was almost holy, it was very hard to be around him when he would do it. He was actually next to a piano and would tinkle while he was thinking. He would just tinkle with his right hand. I had been with him on more than one occasion when he did it. He would go back to it. His workroom had a big upright, at least the one or two times I worked with him in that room. He’d be writing. It was more of a trance than stopping and thinking. He wouldn’t talk. He’d be in a trance.

I think for Anthony, whatever success he’s had as a writer, the idea that he was a performed composer thrilled him. After the original run, we converted the full score of Oedipus (that’s everything that’s in the play) into a cantata, and Burgess wrote himself a narrative part. It’s not a very long play, so we coupled it with A Midsummer Night’s Dream with which we did the same thing. We took a score I wrote for Canada which was very elaborate and full, maybe half-an-hour of music, and he wrote himself a narrative. So we did one half Oedipus and one half A Midsummer Night’s Dream. He called it The MND Show. And he made an entertainment when we performed it in New York at the Whitney Museum. The big surprise for me was when you looked out at the audience they were speechless and I realised it wasn’t just celebrity talking. It was right at the time of Watergate and what he really hit on in his narration was the mystery of the land. Where is the truth? It was perfect timing and it just landed.

Afterwards, we were commissioned by the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center to do a concert piece for two famous sopranos, Beverly Sils and Eileen Farrell. We went to meet with the women at Sils’s apartment on Central Park West. He smoked in front of the two sopranos and they were hysterical. They were so angry. That didn’t work out at all.

We kept very much in close touch until the end. I spent a year in Manchester working at the Royal Exchange. He was fascinated with my then wife Martha, the violinist, who was Czechoslovakian, American born, a Jewish girl with blonde hair and blue eyes, and her family history. One of my favourite of his books, which was Any Old Iron, which was about Arthur’s sword. He was fascinated by the Diaspora, how an Israelite became a blonde, blue-eyed Czechoslovakian musician in America, so he made her Zipporah in the book, a Manchester percussionist. He really picks up on the personality.

Stanley Silverman is a composer, musician, arranger and guitarist who has worked in film, theatre, television, classical music and pop music. In 1973, he collaborated with Anthony Burgess on Oedipus the King for the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis. He has worked with Pierre Boulez, Arthur Miller, Paul Simon and Sting. He lives in California.