Object of the Week: The Quest for Fire Production Folder

-

Graham Foster

- 25th July 2017

-

category

- Object of the Week

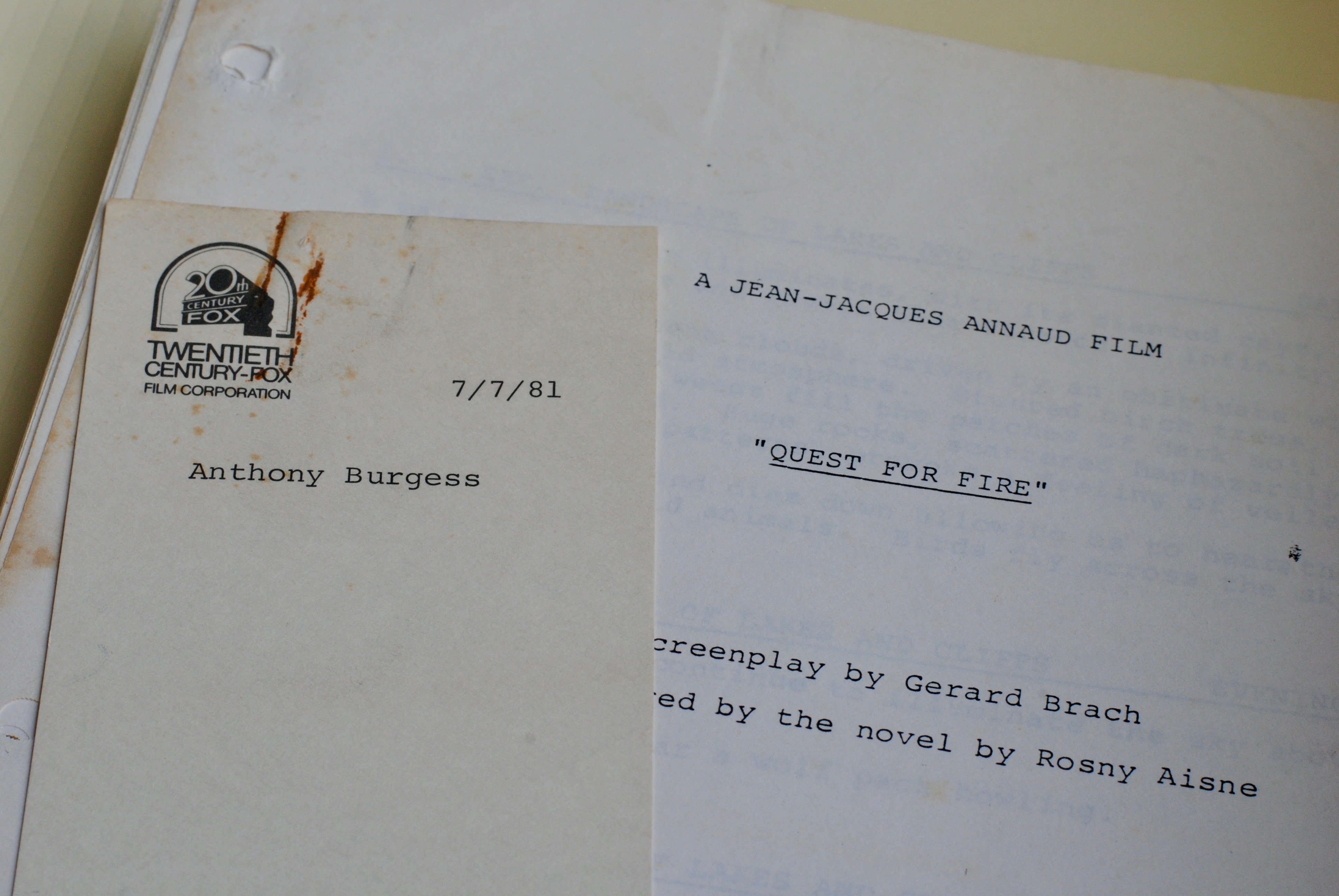

In 1980, Anthony Burgess was recruited by the producer Michael Gruskoff to invent a new language for the Ulam tribe of prehistoric people in Jean-Jacques Annaud’s Quest for Fire. The film is set 80,000 years ago, and tells the story of a primitive tribe’s efforts to guard their precious fire, something which they know how to keep aflame, but do not know how to create. When a neighbouring tribe attack the flame is lost, and members of the Ulam tribe embark on a dangerous quest to find it again.

Gruskoff was most famous for his work producing the Douglas Trumbull science fiction film Silent Runnings and Werner Herzog’s version of Nosferatu, while Annaud would later go on to film The Name of the Rose and Seven Years in Tibet. When it was released in 1981, Quest for Fire became one of the most successful films with which Burgess was involved that made it to cinemas.

The archive of the Anthony Burgess Foundation contains several items which relate to Burgess’s involvement with the film, from correspondence and contracts, to publicity materials, production files, scripts and the dictionary of Burgess’s invented Ulam words.

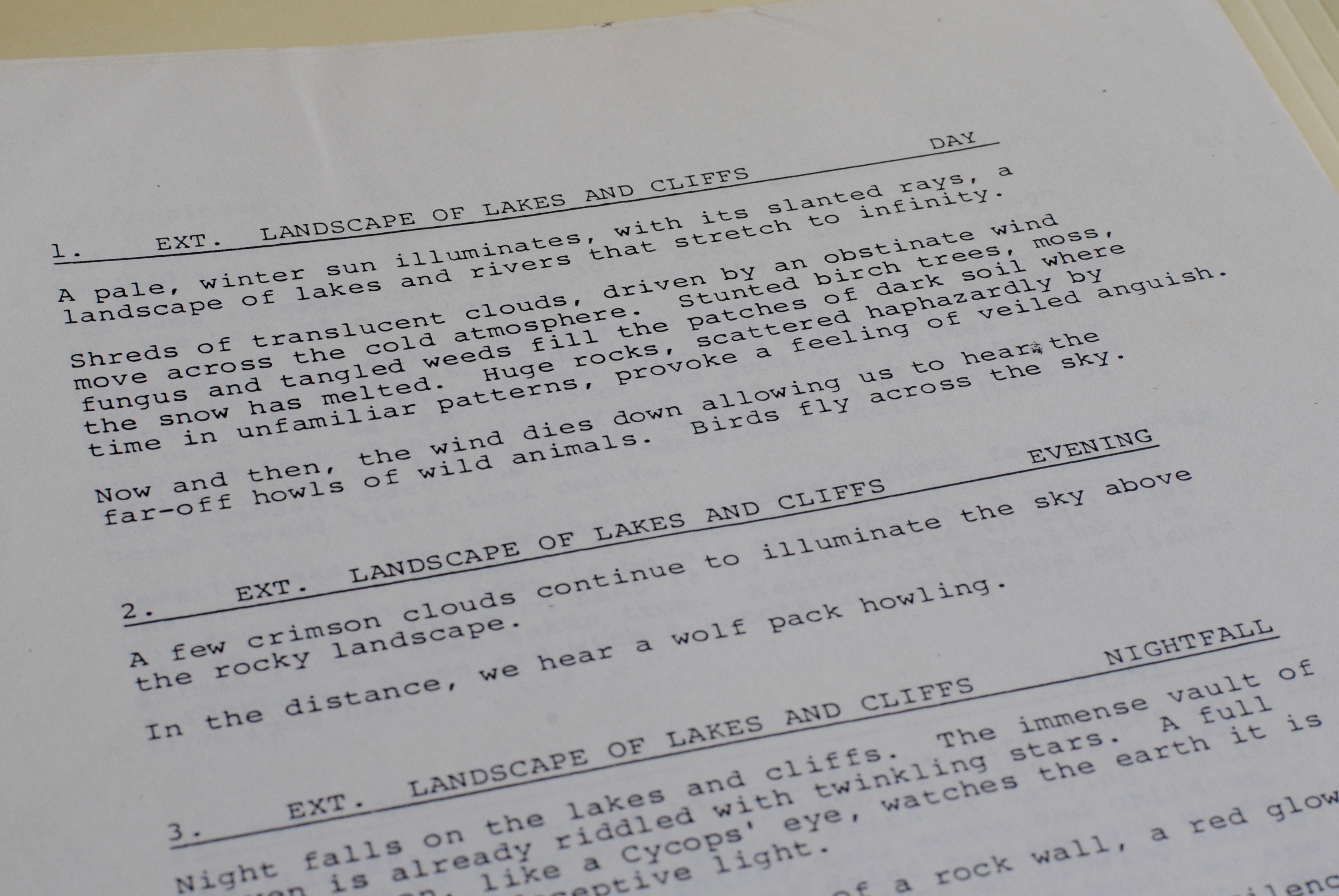

The screenplay for Quest for Fire, based on the novel La Guerre du Feu by the Belgian author J.H. Rosny, was written by Gerard Brach, a frequent collaborator of Roman Polanski. The draft screenplay in the archive consists mostly of stage directions, with very little dialogue. It was Burgess’s job to develop the language. In a 1981 article for the New York Times, Burgess remembers early discussions with Gruskoff and Annaud:

‘Both Jean-Jacques Annaud and Michael Gruskoff had some vague notion that the Stone Age people of Europe spoke the old Aryan tongue we call Indo-European, but they were several scores of thousands of years out. What they would certainly not be speaking was a tonal language of monosyllabic roots like Chinese; nor would they be grunting and hallooing in Tarzan fashion. Their language – or languages, since several tribes were breaking their long isolation in search of fire – would have a faint resemblance to what we know of Indo-European, with an accidence of some complexity, meaning terminal gradations in nouns and verbs.’

Annaud remembers Burgess’s linguistic skills as the primary reason the production approached him: ‘I went to Anthony Burgess because before being this famous icon of literature he started as a teacher of languages. For example, he was a teacher in Malaysia where he had to learn Chinese in order to teach English to the Malays. His real speciality was ancient Icelandic, for which he had to learn Danish, all the Scandinavian languages, Norwegian. He also knew how to speak Laplandish. He knew about 25 languages and he was just phenomenal to work with, such a character.’

Burgess invented a complex language of ‘sense-sounds’ and worked with the anthropologist Desmond Morris, who devised physical gestures to go along with the language. They did, however, allow some simplicities so that the actors could easily replicate the language and gestures, with Burgess producing a dictionary of Ulam words for the production. Burgess prefaces the dictionary with the direction: ‘all the words must be said with DIFFICULTY, AWKWARDNESS, and VERY SLOWLY. The sounds come from the chest, and the bottom of the throat. To speak is an acrobatic effort for the ULAMS. They use speech when they have no other means of communication, such as in the dark and in the distance’.

Some samples from the Ulam dictionary include:

DAWN: djøn

NOON: djø::n

DUSK: djø-n

FIRE: ’atra

GOOD: ’otim

HELLO: gaiS

REINDEER: tir-dondr (animal-tree)

In his essay ‘Firetalk’, Burgess explained his intention to make the language more complex that the simplistic parodies of ‘caveman’ grunts: ‘People usually expect what is called a primitive language to be simple, but the farther back you go in the study of language, the more complications you find. Simplicity is the fruit of the ability to generalize, and primitive man found it hard to generalize. One word for this man’s weapon and another word for that man’s weapon, but no word for weapon.’

Burgess’s inventions were so successful that Annaud remembers the actors had memorised all of their lines in the script and could improvise in the Ulam language.

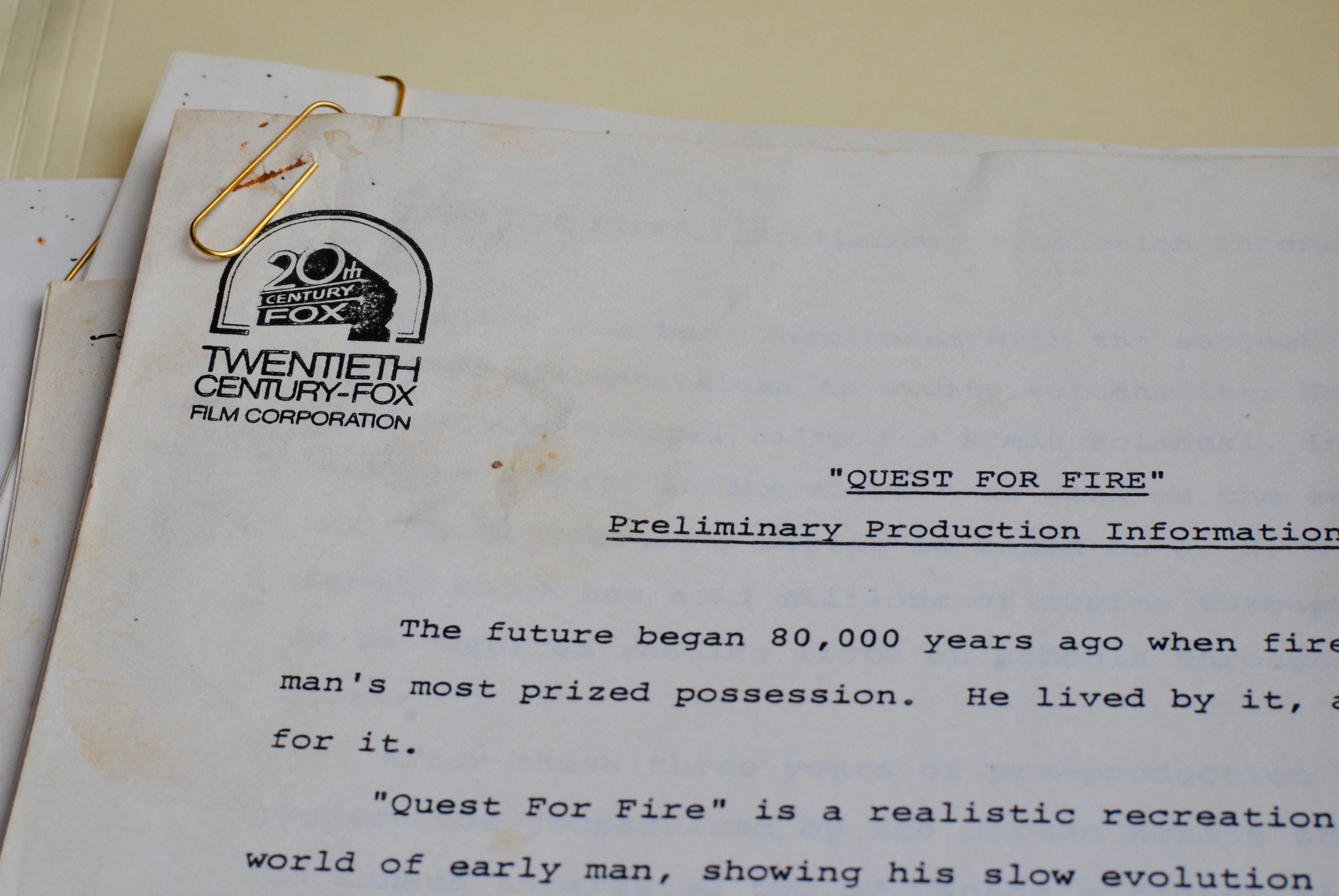

The production notes in the archive at the Burgess Foundation reveal that Twentieth Century Fox attempted to market the film as a companion piece to 2001: A Space Odyssey and Star Wars, stating that it is a ‘science-fantasy’ which takes viewers into the past rather than the future. Shooting took place on three continents (in Canada, Scotland and Kenya), and the film had a budget of 12 million dollars. Annaud remembers having difficulty convincing the studio to release the film once it was finished, and claims it only reached cinemas because Frank Sinatra was so enthusiastic about an early screening.

Ulam is just one of the languages that Burgess invented. A Clockwork Orange is narrated in an invented argot or slang, assembled from existing languages (primarily Russian). Burgess went on to invent languages for various works: the Castitan language in MF (1971), the language based on Indo-European for the ritualistic chants in his translation of Oedipus the King (1973), and an unpublished invented language based on a fusion of English and Hebrew, originally intended for Man of Nazareth (1979).