Object of the Week: Burgess’s Italian Cookbook

-

Graham Foster

- 8th August 2017

-

category

- Blog Posts

-

tagged as

- A Dead Man in Deptford

- Archive

- Beard's Roman Women

- Burgess 100

- Burgess in Rome

- Charles Dickens

- Collections

- Elizabeth David

- Europe

- Food and drink

- garlic

- Italy

- Journalism

- Little Wilson and Big God

- lowscowse

- Malta

- Nothing Like The Sun

- Object of the Week

- Penguin Books

- Tremor of Intent

- You've Had Your Time

Anthony Burgess’s copy of Italian Food by Elizabeth David is battered, ripped and stained, suggesting heavy use. It also contains scraps of paper which mark certain recipes, giving an insight into what Burgess may have been cooking.

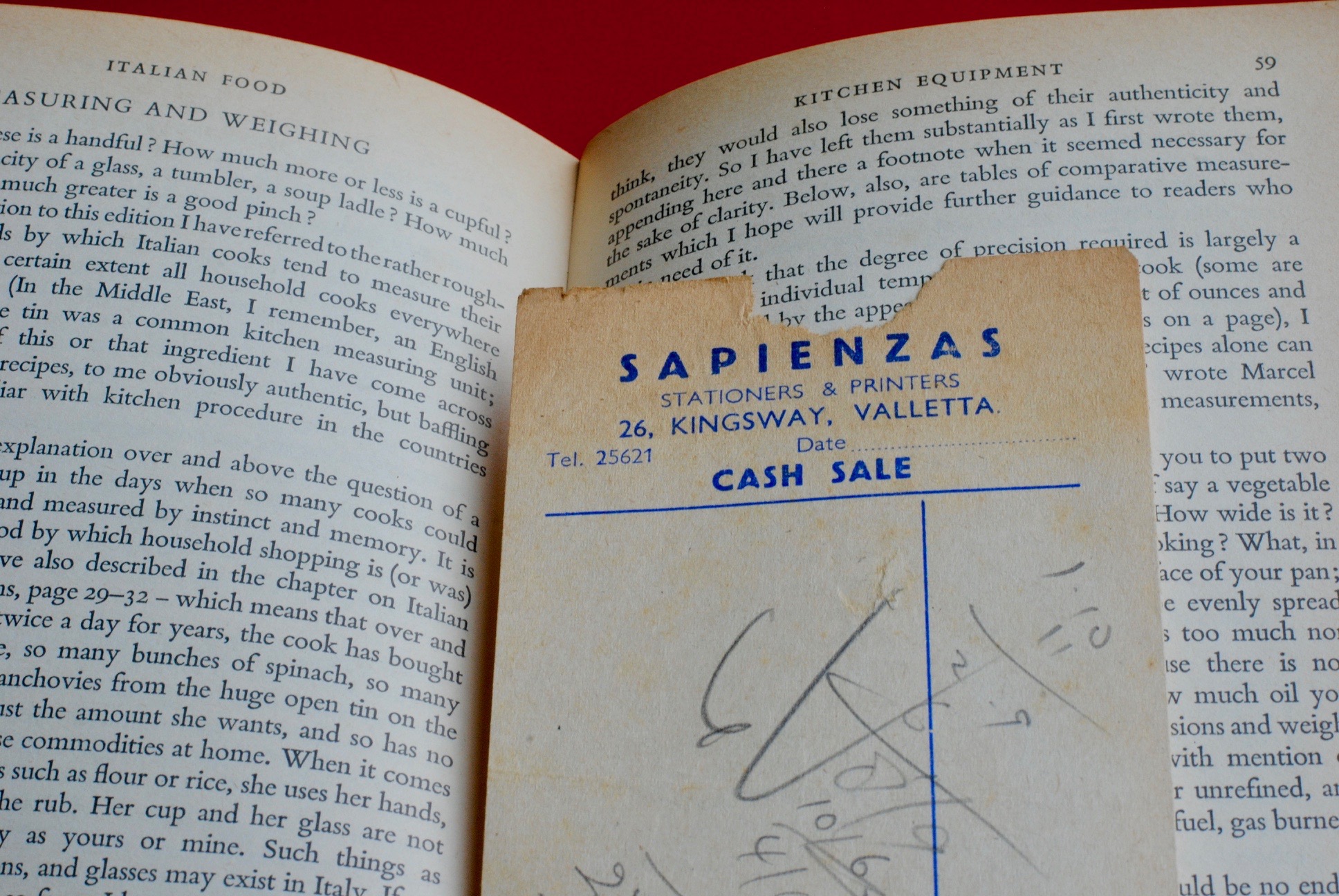

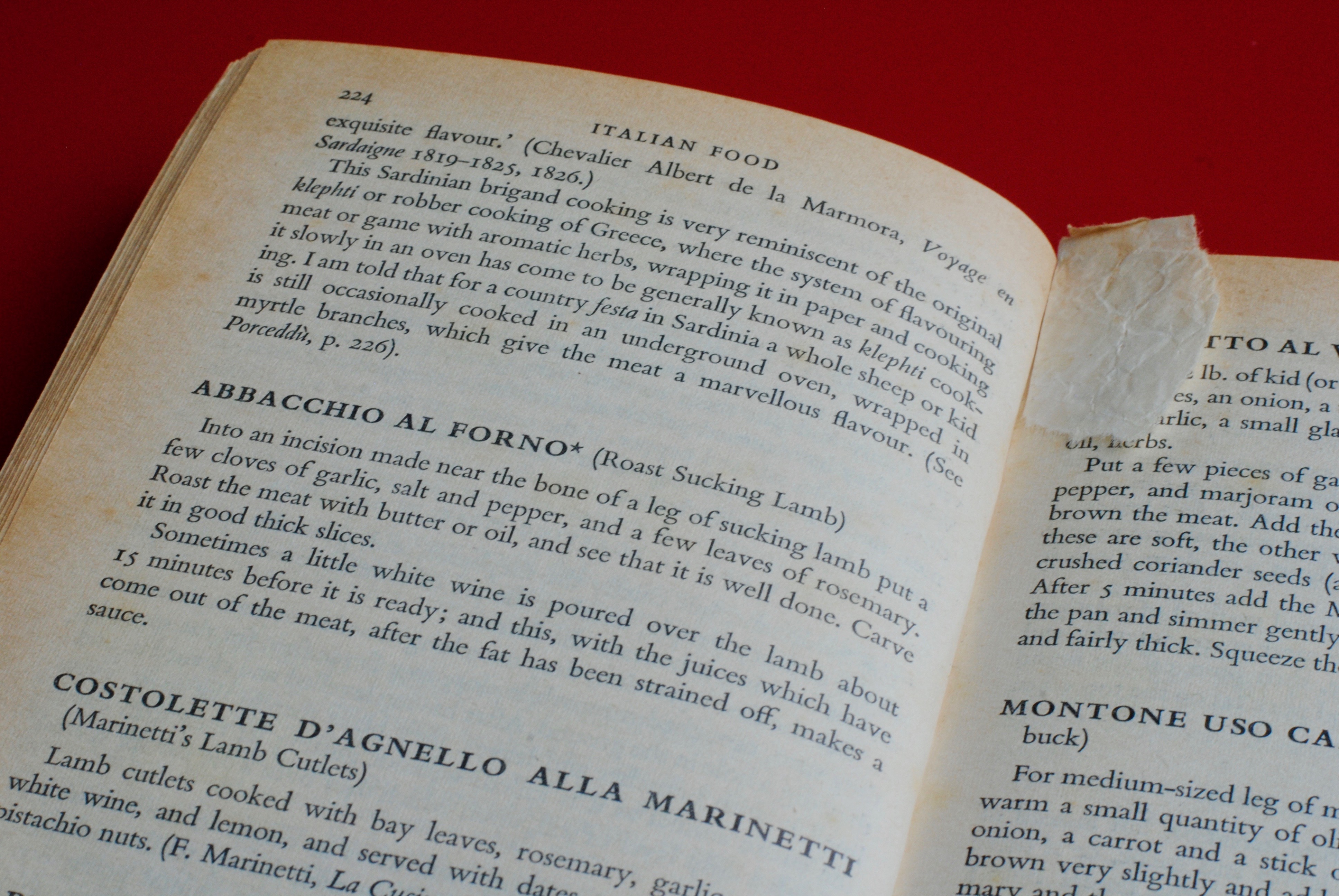

Burgess’s edition of Italian Food was published by Penguin in 1967, and there is internal evidence that he was using it during his time in Malta. Some of the pages that have been marked include a recipe for Abbacchio Al Forno, or Roast Suckling Lamb, a typically Burgessian dish. Burgess writes about roasting lamb in various places. In a 1984 article for Gourmet magazine titled ‘The Glory of Garlic’, he shares his recipe for gigot of lamb, which shares some elements with David’s recipe, particularly the technique of pouring white wine over the meat while it is roasting.

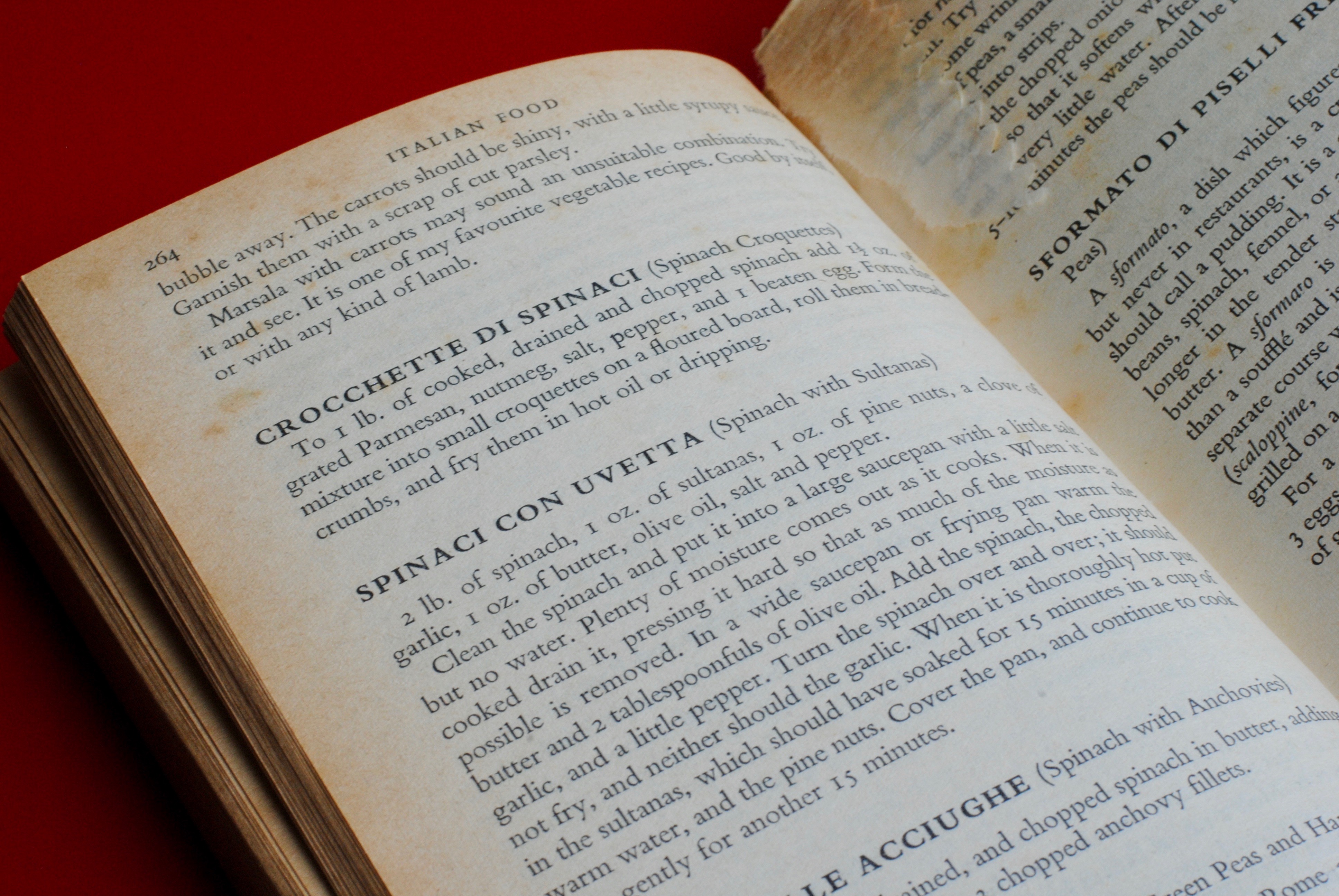

Pages containing recipes for marrow and courgette are marked in the book, as well as recipes for spinach, including spinach with sultanas and anchovies, and spinach croquettes, in which the spinach is coated in a parmesan and nutmeg batter and fried in hot oil or dripping.

Pages containing discursive histories of Italian food have also been marked, such as a long discussion of the history of pasta. It is hard to know if this marked passage has inspired any of Burgess’s writing. His fictional portrayals of pasta tend to be brief, whether is it Enderby’s ‘spaghetti formaggio surprise’, or Ronald Beard’s strange use for spaghetti strands in Beard’s Roman Women. Elsewhere, Burgess writes about his preference for the ‘pasta-less refinements of Bologna and Milan.’

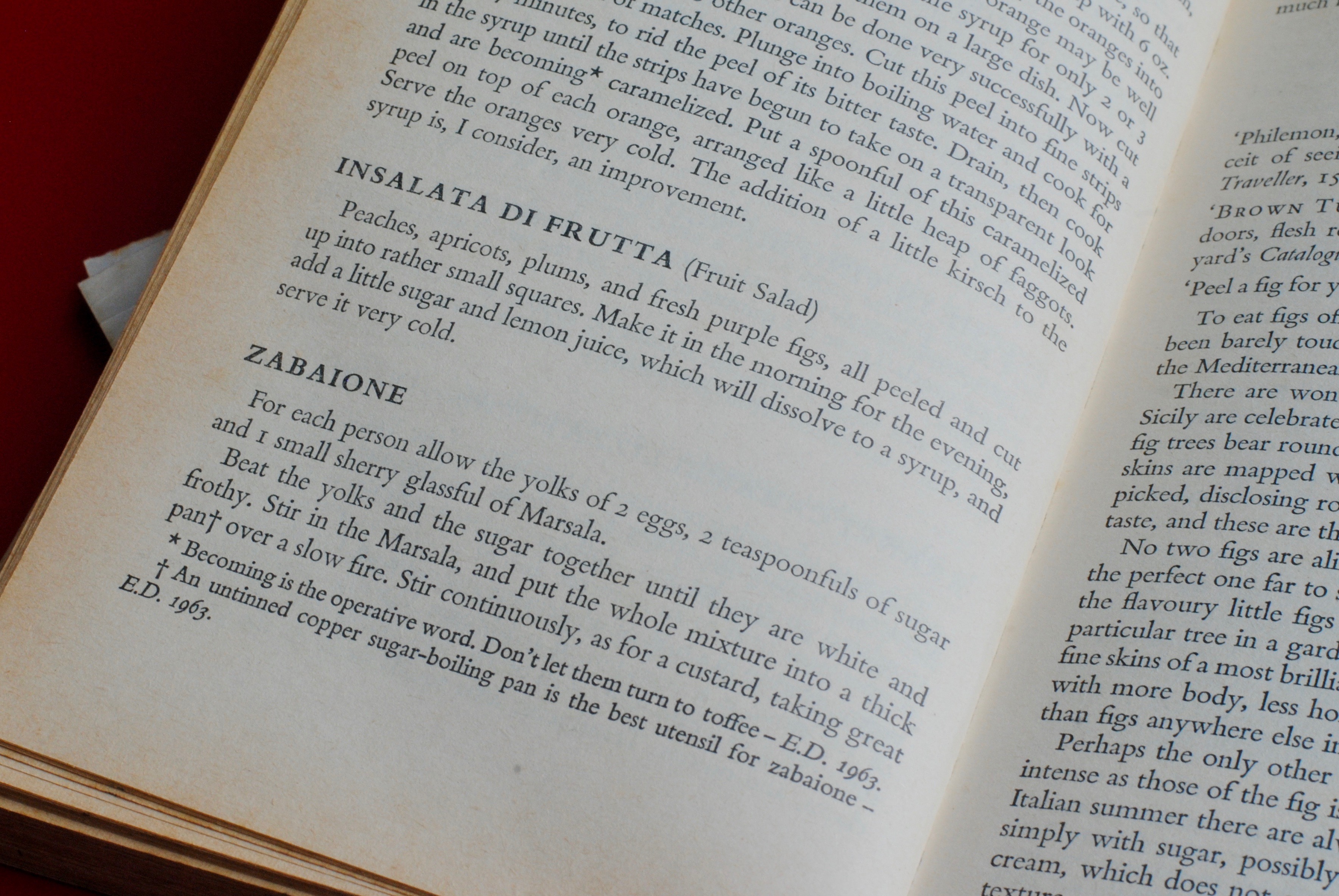

In You’ve Had Your Time, the second volume of his autobiography, Burgess remembers that his first solitary meal after the death of his first wife consisted of Veal Marsala followed by a zabaglione — the same meal that his fictional character Ronald Beard enjoys in the same circumstances. There are recipes for both of these dishes in David’s book, the former under the name Saltimbocca (which David translates as ‘jump in the mouth’), and the latter containing the exact method Burgess describes in his autobiography and Beard’s Roman Women.

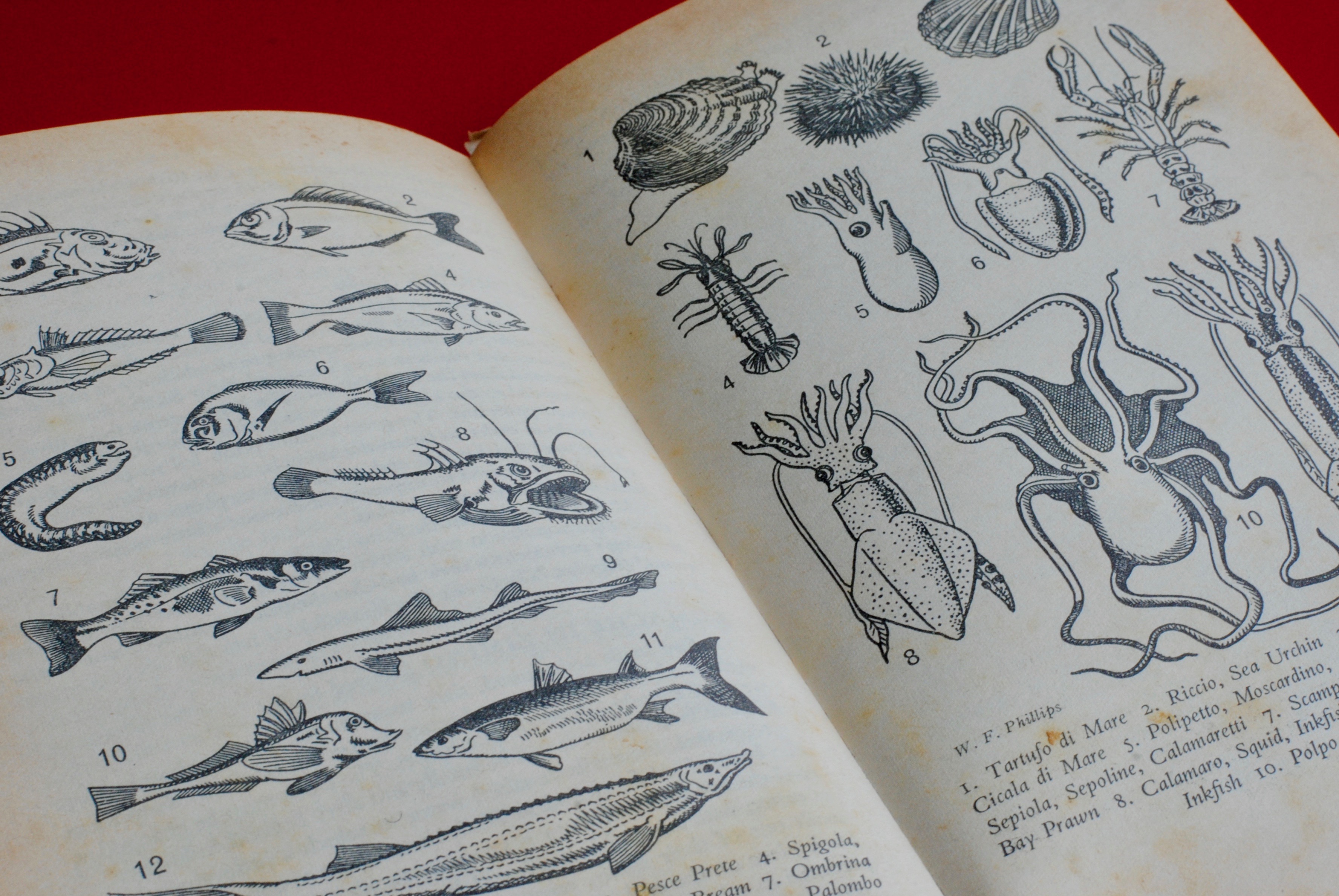

Burgess’s love of food and drink is well documented, and it is a constant preoccupation in much of his fiction. After moving to the Mediterranean, Burgess said that he had taken a liking to ‘extreme climates, fights in bars, exotic waterfronts, fish soup, a lot of garlic.’ Yet, his culinary upbringing continued to haunt him, even when he was surrounded by the garlicky meals of Southern Europe. As he said in an interview, ‘I am sometimes mentally and physically ill for Lancashire food — hot pot, lobscowse and so on — and I have to have these things. I’m loyal to Lancashire, I suppose, but not strongly enough to wish to go back and live there.’ This passion for food, whether the cuisine of his Mancunian roots or exotic feasts, is an important element in Burgess’s fiction.

‘You can always tell a bad novelist by the way he or she deals with eating,’ he writes. ‘After breakfast they resumed their journey. But what, for heaven’s sake, did they have for breakfast? Dickens never leaves us in any doubt: hot muffins, mutton chops, grilled kidneys, eggs like miniature dawns, thick slices of good red beef, coffee hot and strong like a punch to the gullet.’

It comes as no surprise, then, that Burgess’s fiction often dwells on descriptions of food and drink. For example, when the fictional poet Enderby is living in Hove on the south coast of England, he is seen making a hare stew, ‘with carrots, potatoes and onions, seasoned with pepper and celery salt, the remains of the Christmas red wine poured in before serving.’ In his two Elizabethan novels, Nothing Like the Sun and A Dead Man in Deptford, Burgess creates much of the atmosphere by writing about food. When Christopher Marlowe (known as Kit) undertakes a spying mission to the Netherlands, he samples the Dutch cuisine after spending a night sleeping above a bakery: ‘The beer hot and roasted apples pounded in, then ginger, nutmeg, cinnamon, cloves, then there were apple shreds floating in beer as shorn wool in a windstorm. Kit got the reward his nose of the night claimed in fresh bread and Dutch butter.’

Burgess also writes about gluttony. In a scene from Tremor of Intent, secret agent Denis Hillier, travelling on a passenger ship, engages in a vast and competitive banquet with the shadowy Mr Theodorescu. In one sitting, the men gorge on lobster medallions, fillets of sole, shellfish tart, soufflé au foie gras, avocado halves with caviar, filet mignon à la romana, roast lamb, onion and Gruyère casserole, pheasant with pecan stuffing and game chips, peach mousse, pears in chocolate sauce, Grand Marnier pudding, nectarine flan, chocolate rum dessert with whipped cream, and apple tart normande with Calvados. This is accompanied by champagne and lashings of red wine. Afterwards, Hillier goes above deck to visit the ‘traditional vomitorium’, as Mr Theodorescu calls the ocean. Burgess’s love of everything gastronomic helps make this scene a comic nightmare of over-rich cuisine.

He also wrote frequently about food in non-fiction books. The first volume of his autobiography, Little Wilson and Big God, makes frequent reference to the importance of food in his life. A particularly potent example is in his memory of meeting a woman in Spain during the war. He remembers the room where this meeting took place as ‘smelling of garlic and cheap scent. And yet I have learned to associate garlic with the erotic.’ Burgess wrote about food in various other places. He often mentioned the importance of tea: ‘Perhaps tea is so woven into the stomach linings of the British that they cannot view it in either a scholarly or aesthetic manner. It is a fact of British life, like breathing.’ He wrote of his Irish roots through a culinary filter: ‘Brought up in an Irish family that had been used to poverty, I still prefer Irish stew and mutton hash to caneton à la presse and veau Marengo.’

It is clear that Burgess found food and drink to be fundamental ingredients in various forms of writing. ‘Great writers love life,’ he writes, ‘this being their subject-matter, and life is food as well as lust, hate and the other innutritious things that come between meals.’