The Black Prince: An Interview with Adam Roberts

-

Burgess Foundation

- 9th October 2018

-

category

- Publications

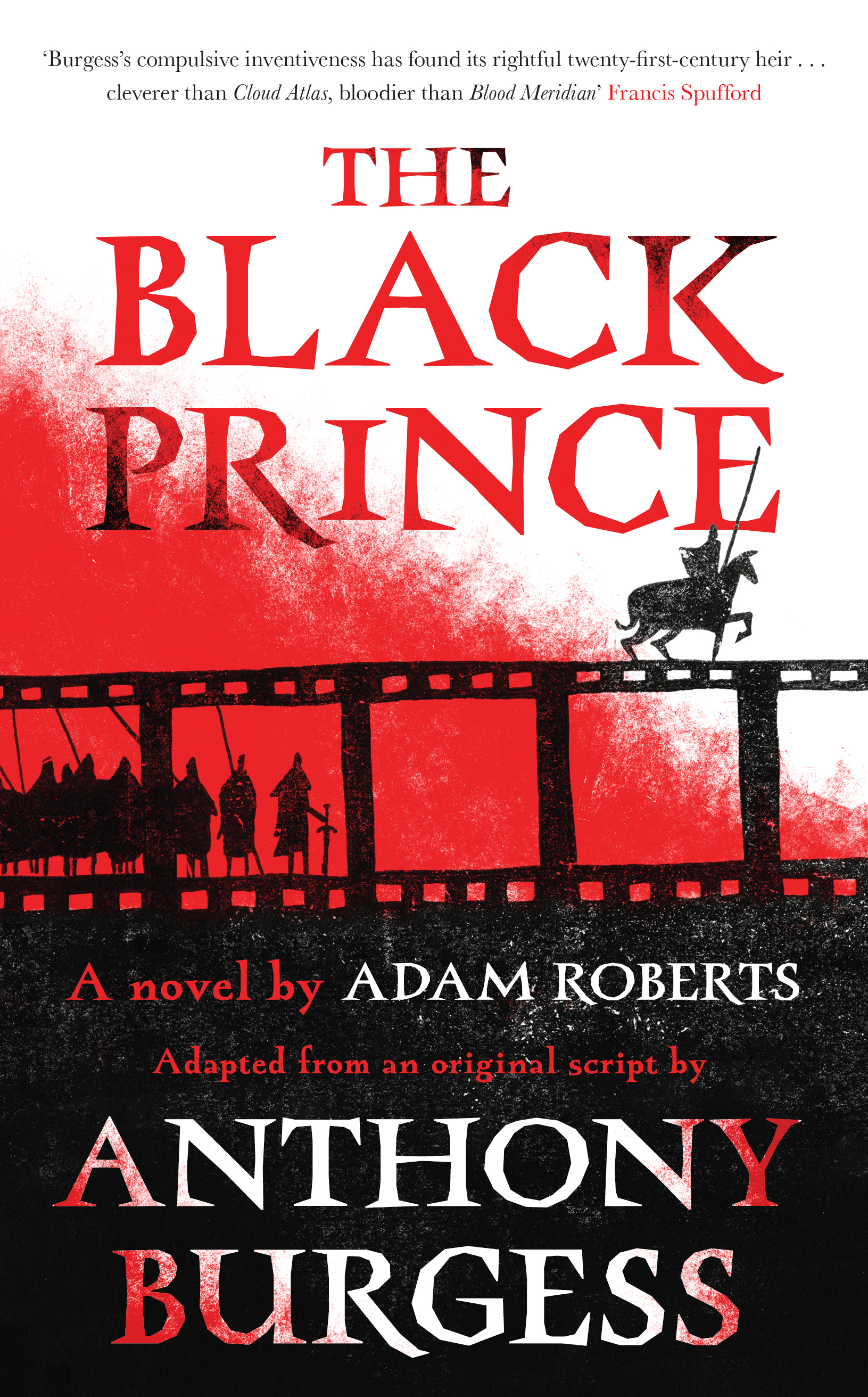

In the early-1970s, Anthony Burgess worked on a screenplay for a proposed historical film about Edward, The Black Prince. The completed screenplay was never published and gathered dust in the archives at the Burgess Foundation until Adam Roberts discovered it. He began work on adapting it into a new novel, The Black Prince, published now by Unbound. He stopped by to talk to us about his inspiration, his research process, and the difficulties of writing in the style of Anthony Burgess.

Who was the Black Prince?

He was the eldest son of Edward III, the fourteenth-century King of England (and bits of France); but he died before he could accede to the throne himself, hence he’s always known as prince. He was also a warrior, and lead the English armies during the hundred years war — indeed, he was regarded in his day as the greatest warrior in Christendom, and the flower of chivalry. He certainly masterminded some of the most amazing battlefield victories of the age, often against much larger and better equipped French armies. We don’t know why he was called ‘Black’ (indeed, we’re not even sure he was called ‘Black’ during his lifetime: the earliest usage dates from more than a century after his death) — but there are two main theories: one, he was called that because he wore specially-made black armour on the battlefield; or two he was called that because he was so notably brutal towards the Frenchfolk he fought. Both of those things are true. His tomb is in Canterbury Cathedral, and his armour is hung over it so you can see for yourself!

Tell us about Anthony Burgess’s screenplay. What did you find exciting about it?

Just reading it was exciting: Burgess’s own typescript, with some of his own handwriting on it! A text seen by nobody outside the Burgess collections! That said, there was a small quantum of disappointment associated with getting hold of a copy of it. When I first talked to the Burgess Estate and the Burgess Institute about The Black Prince project, we were going on the evidence of an interview Burgess gave to the Paris Review in the 1970s that he had written “eighty or ninety pages” of a first draft of the novel; and I was hoping that I could take those pages and complete the novel on the strength of them. But Andrew Biswell checked the archive and couldn’t find those pages, assuming they ever existed. So the screenplay was all we had. Still, there was excitement in reading it, and more so in breaking it down: taking it apart to see how AB had structured his telling — a nine-part form divided into three lots of three — because that then became the frame for my novel. I also tried to reuse as much of Burgess’s actual dialogue, although in the end I couldn’t use it all. Good film dialogue really isn’t the same thing as good novel dialogue.

When did you first discover Burgess? What is your favourite of his novels?

I grew up, through the 1970s and 1980s, when Burgess’s fame was at its height, and he always seemed to be appearing on Parkinson on the telly, or reviewing a new book in the Sundays. He was part of the cultural climate of my youth. So for instance, I vividly remember the kerfuffle about the 1980 Booker Prize (as it was then called) when Earthly Powers was shortlisted but Golding’s Rites of Passage won: plenty of people thought that was an injustice. I think it was an injustice! So, I read a number of his books when I was younger: Clockwork Orange of course, but also Earthly Powers, End of the World News, Kingdom of the Wicked, Any Old Iron — all quite big sellers in their day. It’s a bit over-obvious to say it, but my favourite probably is Earthly Powers — it’s such an extraordinary novel. That said, I’ve read Napoleon Symphony several times, and each time it gets richer and more astonishing. One of the greatest historical novels of its time, I think.

Was writing the Black Prince more than just impersonating Burgess? How hard was it to recreate his voice?

Well, I had to do some impersonation of Burgess, or the project wouldn’t have made any sense. More precisely I had to write an impersonation of Burgess writing an impersonation of John Dos Passos — because that was, very particularly, his plan for the novel. To that end I re-read the U.S.A. trilogy, and then read through the whole of Burgess’s body of work — an amazing experience, that completely converted me to Burgess as a great master of the form. I mean, I admired and respected him before I started on this work; but now I think he really is one of the great novelists of the century. Once I had the whole body of work swimming around in my head, I set to work writing in a way that ventriloquised Burgess’s distinctiveness, without entirely sacrificing my own voice as a writer.

Why should we read Anthony Burgess today?

Because he was such a good novelist: so varied, so energetic, so alive, so profound and because he worked so restlessly at keeping the novel new. I can’t think of another writer, or at least not a writer since Burgess’s own great inspiration, Joyce, who was able to combine genuine fictional innovation and experimentation with genuine populist readability. Because, in short, he’s brilliant.

The Black Prince by Adam Roberts (Unbound, £16.99) is out now and available from your favourite bookseller.