Editing This Man and Music

-

Christine Lee Gengaro

- 27th March 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

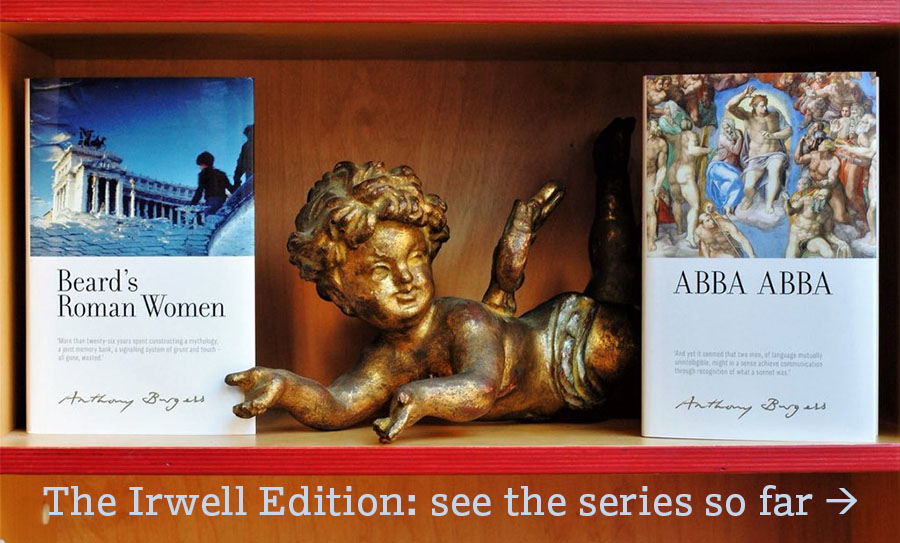

Christine Lee Gengaro writes about editing Anthony Burgess’s This Man and Music, the latest release in the The Irwell Edition of the Works of Anthony Burgess.

Anthony Burgess’s This Man and Music must be one of the author’s most oft-quoted books. As a non-fiction work about music and literature, it is a fertile source of sound bites about Burgess’s musical history, his compositions, and his observations about the connectedness of music and literature.

I came upon This Man and Music when I was writing my dissertation (a study on the music in A Clockwork Orange) and needed some background information about Burgess, the composer. There I found an account of his discovery of Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, his failed childhood violin lessons, his father’s reluctance to share more than a single nugget of musical knowledge, and an explanation of the how and why of Napoleon Symphony. There was much more to this book — entire chapters about poetry, a rumination on the nature of performative works of art, a thorough exegesis of his novel MF. But I didn’t need any of these for my research, so I left the rest for another day.

To be fair, This Man and Music may well be the source of many a pithy and witty idea, but it’s a harder sell as a continuous read. The reason for this lies in the twisted history of the text. In editing This Man and Music, it was clear that my first task was to uncover the origin story of this odd little book, and, as a fan of mystery, I dug out my magnifying glass and started investigating.

This Man and Music began with a request in 1977 for Burgess to participate in the T.S. Eliot Memorial lecture series at Eliot College, University of Kent. He accepted, choosing music and literature as his topic. He composed four lectures for the occasion and presented them in the spring of 1980. A perk and condition of speaking at this series was that Faber and Faber would publish the lectures as a book. Around the same time, Burgess was asked to participate in another lecture series at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio. He chose a similar topic and again gave four lectures in the fall of 1980. There was a considerable amount of overlap between the two sets of lectures, something I discuss in depth in the new edition.

In the subsequent year, Burgess took these two sets, expanded and developed them, and ended up with an eleven-chapter book called Blest Pair of Sirens (the title of the Eliot lectures) that may be described as part memoir, part music lesson, part poetry lesson, part literature lesson. Because Burgess had expanded on the lectures, his literary agent (notably, the book’s dedicatee) sought a new deal with a new publisher, rankling the folks at Faber and Faber. In order to follow the series of events that led to the change in title and the deal with Hutchinson, I had to read through considerable correspondence, most of it housed at the Burgess Foundation. At the end of this part of the story, Burgess was compelled to change both the title and the Foreword, removing all references to both the lecture series.

In the subsequent year, Burgess took these two sets, expanded and developed them, and ended up with an eleven-chapter book called Blest Pair of Sirens (the title of the Eliot lectures) that may be described as part memoir, part music lesson, part poetry lesson, part literature lesson. Because Burgess had expanded on the lectures, his literary agent (notably, the book’s dedicatee) sought a new deal with a new publisher, rankling the folks at Faber and Faber. In order to follow the series of events that led to the change in title and the deal with Hutchinson, I had to read through considerable correspondence, most of it housed at the Burgess Foundation. At the end of this part of the story, Burgess was compelled to change both the title and the Foreword, removing all references to both the lecture series.

As I see it, that small change had a very important consequence; by obscuring the book’s origin as interconnected lectures, Burgess removed a vital piece of information that might have directed readers to expect a loosely connected series of essays and not a traditional autobiographical narrative. The mixed reviews (some shared in the appendices) reflect the result of this change. Some critics — and readers — just didn’t get what Burgess was aiming at, an effect compounded by a title that was misleading.

The second challenge was in the annotation. Burgess’s easy erudition and — let’s face it — tendency to name-drop, made annotation a formidable task. On a single page, one might find references to Greek mythology, musical terms, Viennese desserts, the Bible, song lyrics, and historical figures. And what’s more, it seems like many of the poems, quotes, and lyrics Burgess included were copied from memory, with seemingly no effort to go back and check these details later. Some items were easy to track down, and some were much harder. One misremembered title or misspelled composer name might lead down a series of dark alleys and dead ends. Still, I enjoy the hunt, and there was plenty of hunting to be done: there are nearly 470 annotations for book that’s barely 200 pages.

The third challenge for me was trying to trace the music-and-literature/literature-and-music thread in Burgess’s career not just in this volume, but in articles and other projects. It turns out that Burgess was already playing around with some of the thoughts, quips, and anecdotes from This Man and Music nearly twenty years before in a 1962 article for Listener. Not only did he revisit the topic in his 1980 lectures and then make the relationship between literature and music the central theme of This Man and Music, he went back to the same well again in 1988, for yet another article for the Listener. What did Burgess title this article? Well, from my perspective, he put a nice, neat little bow on the whole thing by unearthing the original title of his Eliot lectures, calling the article ‘Blest Pair of Sirens’.

The endeavor of editing This Man and Music has been a meditation on a man’s obsession with a certain idea, but also his ability to reuse, recycle, and riff seemingly endlessly on the topic. This Man and Music is not a long book, yet it is dense in ideas, references, and lessons. It’s no wonder that all of us musical Burgessians have found it an inexhaustible source of quotes and provocative ideas. There’s much more to it than meets the eye (or the ear); one just has to begin the journey with an openness to go wherever Burgess leads.

Christine Lee Gengaro is a Professor in the Music Department at Los Angeles City College.