Newly conserved books in the Burgess Foundation collection

-

Anna Edwards

- 14th April 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

It’s one thing to collate an archive collection: it’s another thing to preserve it. We explore some newly conserved books in our archive.

Preserving and safeguarding the collection of books, archival records and objects belonging to Anthony Burgess is at the heart of the Burgess Foundation’s mission, and all those who access, manage and use the collection play a part in ensuring its survival for future generations.

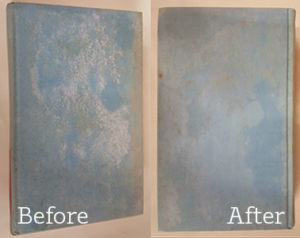

Preservation encompasses a broad range of activities, one of which is remedial conservation. Since 2011, we have been working with Formbys Ltd, a specialist in book conservation and restoration, to carry out vital conservation of our library collection; work which has been supported by contributions to the Burgess Foundation’s Friends scheme. This is the second in a series of blogs which shares details of our ongoing work with Formbys: read the first one here.

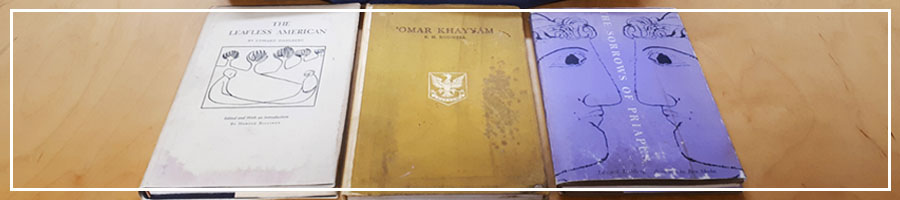

Books from Burgess’s library that have recently been conserved include:

• a 1931 edition of the poetry of Omar Khayyam

• volumes 2 and 4 of Aleksandr Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1964), translated and with a commentary by Vladimir Nabokov

• first editions of The Sorrows of Priapus (James Laughlin, 1957) and The Leafless American (Roger Beacham, 1967) by Edward Dahlberg

• To Be A King: A Novel about Christopher Marlowe (Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1976) by Robert DeMaria

Treatment included surface cleaning, lining dustjackets with archival paper, rebacking spines, and the use of specialist solvents. As a result of this important work, we are pleased to be able to make these volumes available to visiting researchers once more.

The poetry of Omar Khayyam

The poetry of Omar Khayyam

This collection of poetry by Omar Khayyam (1048-1131) initially belonged to Burgess’s first wife Llewela (or Lynne, as she was known) and is among the oldest books in our collection. It is one of a number of books owned by Lynne and, thanks to her inscription at the front of the book (“L. Wilson”), we are able to date its acquisition to some point after her marriage to Burgess (real name: John Wilson) in 1940.

The volume is one of two copies of Omar Khayyam’s poetry, known as the Rubaiyat, in the Burgess Foundation’s library; the second (in English and Malay) dates from 1944 and was acquired while Burgess was teaching in Kota Bharu, Malaysia, in the 1950s.

Burgess writes about Omar Khayyam in Urgent Copy and takes inspiration from his poetry in This Man and Music, which has recently been republished as part of the Irwell Edition of the Works of Anthony Burgess. Summarising his argument in the essay titled “Under the Bam”, Burgess writes: “The first quatrain of Omar Khayyam, …, describes the Cyrus of the day taking the dome of the mosque and inverting it to make a cup, so that it may be filled with the white dry wine of the dawn. The Persian word for cup is jam, and for dome or roof bam. I have been suggesting, no more, that the study of English verse ought to be housed in the halls of a wider study of rhythms and stress – be, in fact, under the bam of music.”

Aleksandr Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin

Burgess also makes passing reference to Omar Khayyam in his 1965 review of Nabokov’s translation of Eugene Onegin as part of a broader discussion of some of the challenges of literary translation: “If we want to read Omar, then, we must learn a little Persian and ask for a good, very literal, crib. And if we want to read Pushkin we must learn some Russian and thank God for Nabokov.” (“Pushkin and Kinbote”, Encounter, 1965).

Nabokov’s translation of Onegin was published by Routledge and Kegan Paul in 4 volumes in 1964 and the novel had been a key influence on Burgess’s development of the Nadsat language in A Clockwork Orange some years earlier.

As well as reading Dostoyevsky and a number of Russian primers, Burgess owned a copy of Onegin in its original Russian and had memorised parts of the novel during his studies of the language, from which he compiled a modified Russian vocabulary of around 200 words that formed the basis of Nadsat.

The Sorrows of Priapus and The Leafless American

The Sorrows of Priapus and The Leafless American

The remaining books conserved by Formbys are important inscribed texts and reveal more of Burgess’s varied literary connections and friendships.

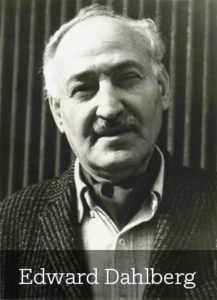

The Sorrows of Praipus (1957) and The Leafless American (1967) are two of eight books and journals by, or relating to, the writer Edward Dahlberg (1900-1977) in the library.

Other examples include Because I Was Flesh: The Autobiography of Edward Dahlberg (1963); Cipango’s Hinder Door (1965); Epitaphs of our Times: The Letters of Edward Dahlberg (1967); Edward Dahlberg: A Tribute (1970); The Carnal Myth: A Search into Classical Sensuality (1970); and a special tribute issue of the TriQuarterly journal (Fall 1970) to which Burgess contributed.

6 of these books have been inscribed by Dahlberg with warm dedications to Burgess. In The Sorrows of Priapus, for example, Dahlberg writes “For my Friend, ally, Anthony, God, we both need help, the ‘Balm of Gilead’. With a thousand [?] & all affections, Edward Aug[ust] 20 [19]70, London.”

![For my Friend, ally, Anthony, God, we both need help, the 'Balm of Gilead'. With a thousand [?] & all affections, Edward Aug[ust] 20 [19]70, London](https://www.anthonyburgess.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/For-my-Friend-ally-300x300.jpg)

Elsewhere, Dahlberg praises Burgess’s recent biography of Shakespeare; refers to their long phone conversation; and encourages Burgess to consider selling his papers to a university in America. An archive of Dahlberg’s own papers was subsequently acquired by Washington University, St. Louis and by the University of Stanford and includes correspondence with Burgess, among many others.

It’s possible that letters from Dahlberg to Burgess are yet to be discovered within the Burgess Foundation’s own collection of correspondence, which is largely uncatalogued.

Robert DeMaria’s To Be A King

Another of Burgess’s literary connections is revealed in his inscribed copy of Robert DeMaria’s To Be A King, a biographical novel about Christopher Marlowe which was a precursor to Burgess’s own Marlowe novel, A Dead Man in Deptford (1993). The book is inscribed “To Anthony, The most literate man in The Western World, Affectionately, Bob DeMaria”.

Burgess had met DeMaria some years earlier and participated in a summer school at the Mediterranean Institute of Dowling College, founded by DeMaria, in Majorca in 1969. Both Burgess and DeMaria recall the experience in their memoirs, You’ve Had Your Time (1990) and Deya: memoirs of an artist colony (2011).

Burgess’s memories of that summer were not entirely happy ones, largely because of problems with his accommodation and efforts spent trying to avoid Robert Graves, with whom he had fallen out over a critical review of Graves’ collected poems and translation of Omar Khayyam some years earlier. Burgess seems to have concealed any personal reservations from others attending the school however. William Chislett remembers Burgess as being “unassuming and kindly” throughout his stay there, “pounding his typewriter” while busy writing the novel MF and “playing Debussy … on piano in the village bar run by William Graves, one of Robert’s sons.”

Burgess went on to write an introduction to DeMaria’s The Satyr in 1972 and to receive copies of the Mediterranean Review, a journal published by the Mediterranean Institute, in the early 1970s, as evidenced by numerous surviving copies in the library.