The strength of a language: Preserving Anthony Burgess’s Malay dictionaries

-

Anna Edwards

- 5th June 2020

-

category

- Blog Posts

When Anthony Burgess moved to Malaya, he needed to learn the language. Take a look at the books that helped his studies, and find out how we’re preserving those books.

On 5 August 1954, Burgess set sail from Southampton with his first wife, Lynne, and their cat, Lalage, ready to begin a new life as a colonial civil servant in Malaya. Five weeks later, he started work as an English teacher at the Malay College in Kuala Kangsar. This was the beginning of his four years as an education officer in Malaya and Brunei.

Several of the dictionaries and grammars that Burgess acquired to help him to prepare for his new role have survived in the library at the Burgess Foundation, and are among those books to have benefited from specialist conservation treatment by Formbys the bookbinders. The titles are as follows:

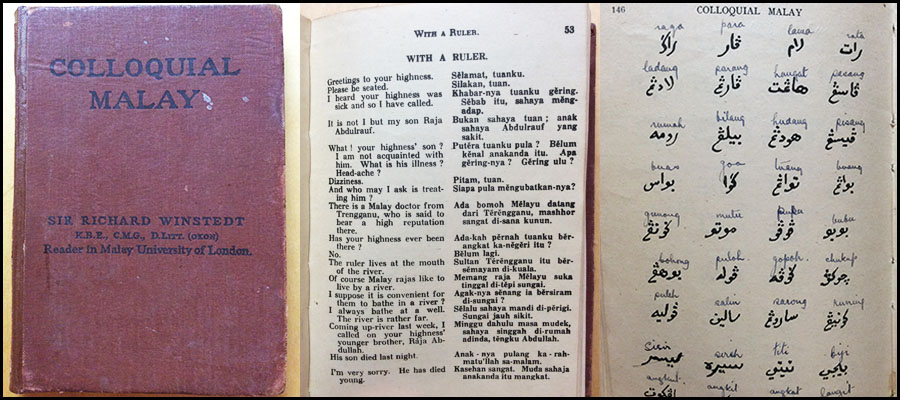

- Colloquial Malay: A Grammar with conversations and an appendix on the Malayo-Arabic spelling by Sir Richard Winstedt KBE, CMG, D Litt (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1945).

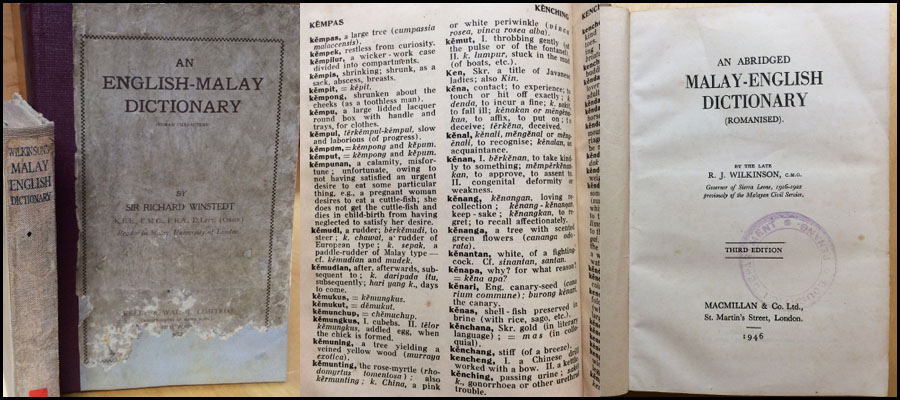

- An Abridged Malay-English Dictionary (Romanised) by the late R. J. Wilkinson, CMG (third edition, London: Macmillan, 1946).

- An English-Malay Dictionary (Roman Characters) by Sir Richard Winstedt KBE, CMG, FBA, D Litt (Singapore: Kelly & Walsh, 1952).

🔎 Here’s a close-up of the ‘With a ruler’ page – opens in a new tab

Burgess’s reliance on these texts is revealed in the type and extent of conservation treatment required: surface cleaning, repair of minor tears, and rebacking spines are suggestive of repeated, heavy use.

Burgess acknowledged the debt he owed to his Malay vocabularies and grammars openly in several works, both fiction and non-fiction. Writing in The Best of Everything (1980), he describes Winstedt’s English-Malay dictionary as the best foreign language dictionary and, in Earthly Powers (1980), he describes Kenneth Toomey, en route to Malaya, turning to his own copy of the text from which he ‘tried to learn five words a day.’ Subsequently, in the preface to Little Wilson and Big God (1987), Burgess lists Winstedt’s dictionary as one of the few works to which he referred while compiling the first volume of his autobiography.

Burgess became fluent in Malay and developed a working knowledge of other languages spoken in the country, especially Chinese, Arabic and Urdu. A certain level of linguistic proficiency was expected of all Colonial civil servants and Burgess threw himself into language-learning, keen to move beyond what he described as the ‘aloof club-frequenting whites’ and to get to know the country and its people.

In Little Wilson and Big God (1987), he describes the Malay language as a revelation:

‘It had learned something that the more conservative tongues of the Indo-European sisterhood did not wish to learn – that properties like gender and word inflection were a needless luxury, that the strength of a language lay in semantic subtleties and not syntactic complexities, that the rigid taxonomy of ‘parts of speech’ meant nothing. The Malay language, and later the Chinese, changed not just my attitude to communication in general but the whole shape of my mind.’

During his years in Malaya, Burgess published his first works of fiction and non-fiction, balancing teaching with a burgeoning writing career. In 1956, Time for a Tiger was published, the first novel in what became known as The Malayan Trilogy, and it was soon followed by The Enemy in the Blanket in 1958.

Later that year, English Literature: A Survey for Students, a history of English literature, was published under Burgess’s real name, John Burgess Wilson. His time in the Colonial Service also stoked a lifelong love of travel, and he remained curious about other cultures and civilisations.

Alongside Burgess’s Malay dictionaries and grammars, the library contains further books acquired during his time in Asia, such as a 1950 edition of D.H. Lawrence’s Selected Poems, stamped ‘Malay College Library’; D. Nichol Smith’s edition of Shakespeare Criticism, stamped ‘Chief Education Officer Kelantan’; and a termite-damaged copy of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, purchased in Singapore.

Visit the Archives Hub for photographs, music, journalism, short stories, film, and furniture within our archive, which can be viewed alongside these published sources and help to create a rich record of this artistically and personally formative period in Burgess’s life.

Burgess’s experiences in Malaya are explored in detail by Matthew Whittle and Graham Foster in the podcast Anthony Burgess and Malaya.

🔎 Here’s a close-up of the English-Malay dictionary text – opens in a new tab