Anthony Burgess and Shakespeare

This resource examines some of the ways in which Anthony Burgess thought about and wrote about one of his greatest inspirations.

- Anthony Burgess and Shakespeare

- Burgess and Shakespeare: a brief introduction

- Burgess teaching Shakespeare

- Nothing Like the Sun: a story of Shakespeare’s Love-Life

- The language of Nothing Like The Sun

- Mr WS: Burgess’s Shakespeare ballet

- Fictional Shakespeares

- Burgess’s identification with Shakespeare

- Burgess and Shakespeare: the podcast

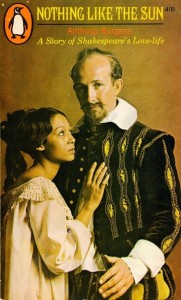

Nothing Like the Sun: a story of Shakespeare’s Love-Life:

In May 1963 Anthony Burgess reviewed — not entirely favourably — Henrietta Buckmaster’s book, All of the Living: A Novel of One Year in the Life of Shakespeare. Her novel was, he thought, unlikely to be the only one of its kind: ‘With the quartercentury looming, many of our foolhardiest novelists must be busy preparing fictional libels on the Bard.’

Burgess was by this point already at work on his own fictionalised biography of Shakespeare. The process of bringing that work on to paper and into print, however, was a difficult one, as is demonstrated by the title of his chapter about it, ‘Genesis and Headache’ (in the book Afterwords: Novelists on the Novel). He describes the work as a labour of tortured love, a ‘ghastly but fascinating task’ that by January 1963 he could put off no longer. The work was “almost haemorrhoidally agonizing” but if it were to be done 1964 was the time to do it. Burgess “would never find a more appropriate publishing date”.

The title of the novel comes from the first line of Sonnet 130: ‘My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun.’ The sonnet is both an unusual love poem and a comment on the style of love poetry written by Shakespeare’s precursors and peers. Shakespeare refuses to give in to the hyperbolic imagery other poets indulge in. His mistress’s lips are not like coral, her cheeks are not the colour of roses, her breath does not smell of perfume and her gait is not that of a goddess. And yet she is ‘as rare/ As any she belied with false compare.’

In his biography of Burgess, Andrew Biswell suggests that the title of the novel ‘is intended as a warning. It implies, with a fair degree of humility, that the fakeries of Burgess’s language are a dim candle in comparison with the brighter Shakespearean sun.’ Burgess imposed a structure governed by mathematical rules: ‘I planned Nothing Like the Sun as a binary movement with a brief epilogue. Part I was to deal with Shakespeare’s puberty and end with his departure for London. Part II, the more complex and the longer, would be about the mature, but not senescent, Shakespeare and end with the shock of syphilis.’ Parts one and two would each consist of ten chapters; chapters in the second part would be double the length of those in the first. These constraints were, to Burgess, like those of a sonnet and ‘it was the shape of a poem — monstrously enlarged — that I wanted for my novel.’

That novel was not simply an experiment in form, however. Nothing Like the Sun was a challenge of research, imagination and language. Burgess sought to tell the story of Shakespeare’s life, pinning his own theories onto his extensive reading, in a language which was both authentically Elizabethan and appealing to the modern ear. Nothing Like the Sun opens with a young WS (as he is known throughout the novel) at home in Stratford-upon-Avon. WS is desperate to escape the confines of a domestic life in which he is distracted from great thoughts by being called in for tea. He hears the ‘world, the wide world crying and calling like a cat to be let in, scratching like spaniels.’ We see him trapped into marriage with the older and possibly already pregnant Anne Hathaway, indentured as a tutor to the sons of a Gloucestershire magistrate, become a lawyer’s clerk, a father, an actor, a writer and a lover.

The subtitle of the novel — ‘A Story of Shakespeare’s Love Life’ — implies that Shakespeare the lover is most important to Burgess. WS becomes involved with Henry Wriothesley, the Earl of Southampton, and later with the woman mentioned in the Sonnets. Burgess finds clues to their names, or rather the letters of their names, which identify them as the ‘Fair Youth’ and the ‘Dark Lady’ of the sonnets. Southampton’s initials reversed make him Mr W.H., the mysterious patron to whom the sonnets are dedicated. In Sonnet 147, Burgess ‘found her name acrostically presented, or very nearly.’ The letters F–T–M–A–H make Fatimah the Dark Lady, the rare mistress, of Burgess’s Shakespeare. She whips him into a fever of love and gives him the lover’s disease, syphilis. Burgess had ‘noticed that Shakespeare’s most superb creations came during a time when, to judge from the imagery of his plays, he was preoccupied with disease — disease in the body, in the spirit, and in the State.’ The novel shows Shakespeare discovering the mark of syphilis, a red sore on the male member, and he later descends into a delirium of unexplained creative inspiration, which produces the final great sequence of his plays.

Many of the details of WS’s life are, as Burgess admitted, pure fantasy. He was careful to point out that there is ‘no documentary justification’ for making Richard Shakespeare limp or Gilbert ‘epileptic, moronic, and afflicted with religious mania.’ But Burgess’s flights of fancy are underpinned by serious research, and a near-obsession with Shakespeare and his world. His explanations of the gaps and inconsistencies in Shakespeare’s life are always interesting even if of varying plausibility. His fiction fills the gaps in our knowledge about Shakespeare’s life, explaining why there is an entry in an episcopal register about a marriage licence for ‘Wm Shaxpere et Annam Whateley’, where Shakespeare went in his ‘lost years’, to whom the sonnets were written and what killed him.

Burgess creates memorable characters in Shakespeare’s life who inspire the characters of his plays. WS’s sister Anne calls their brother Richard — who limps — bristly boar!’ The boar featured in the arms of Richard, Duke of Gloucester. The same brother, years later, cuckolds WS. Richard, Duke of Gloucester, became Richard III. Similarly, the boy heroines of the comedies are prompted by both Annes. Anne Whateley has ‘long white hands and foot high-arching, gentle low pipe like a boy’s voice’; Anne Hathaway dresses up as a page for titillation. But it is Cleopatra who dominates the imagery of the novel. The ‘Avon glowed like Nilus and bobbed with watersnakes’; ‘in a bed of gold that seemed to float like a ship […] Master WH lay on satin cushions’; WS and WH travel down the Thames on a ‘barge new-painted with cloth-of-gold.’ All roads, for Burgess and for WS, lead to the East.

More interesting, perhaps, is the way in which most of the characters appear to be inspired by that of WS himself. He is Romeo when tortured by unrequited lust, Polonius when he says: ‘I do not myself borrow, therefore I may not lend.’ Qualifying that statement he becomes Shylock, ‘save […] perhaps on interest of a crown in a pound and a pound of flesh for the mortgage.’ He is Hermione in the forgiveness he extends to his wife and brother, standing ‘above, blessing, forgiving, with lips untwisted in bitterness, brow all alabaster-smooth, a statue.’ Fatimah tends to WS’s headache with a handkerchief like the one which Othello gives to Desdemona, albeit embroidered with spots rather than strawberries. Burgess’s WS is all of the characters he will write.

Burgess frequently seeks to find or invent similarities between himself and Shakespeare. He goes a step further in Nothing Like the Sun: the novel has a framing device, that of a farewell lecture delivered in Malaya by one Mr Burgess to his ‘special students.’ This connection to the East made Burgess’s Dark Lady a very personal invention. He wanted her ‘to come from the East — a woman like one of [those] I had been hotly attracted to during my time as a colonial civil servant.’ Burgess claimed to understand ‘the desperation that Shakespeare felt for the dark lady.’

‘Mr Burgess’, the fictional lecturer, becomes progressively drunker during the lecture, drinking the samsu (rice wine) that his students have bought as a farewell gift. Burgess himself ‘had lectured on Shakespeare in the Far East, sometimes when not altogether sober.’ In the final pages of the novel, the characters of the lecturer and the playwright become merged. The Epilogue is written in the first person but not, Burgess says, directly that of WS. It is WS ‘trying to speak through the mediumistic control of the story-teller or lecturer, who was myself.’ In his biography of Shakespeare, Burgess claims ‘the right of every Shakespeare lover who has ever lived to paint his own portrait of the man.’ And, like many others, Burgess paints himself into the imagined portrait of Mr WS.

Victoria Brazier