Anthony Burgess and the Censorship of Ulysses

-

Graham Foster

- 12th September 2018

-

category

- Banned Books

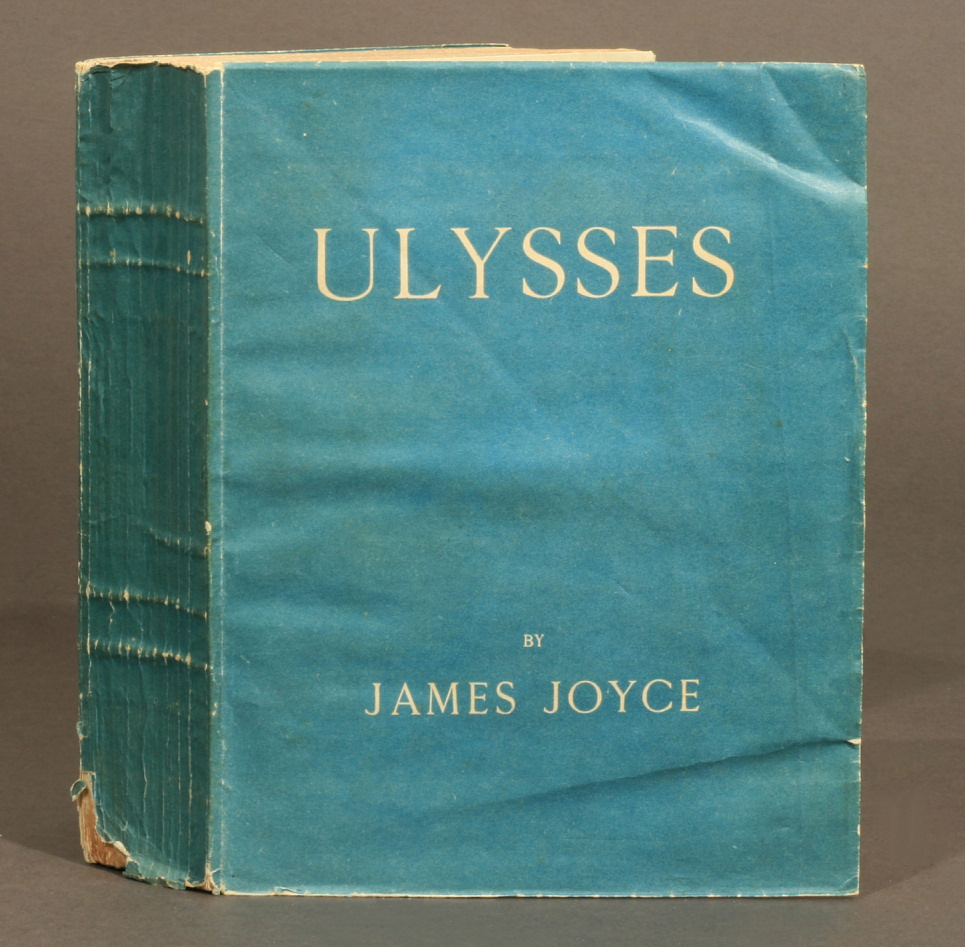

Anthony Burgess claimed that he encountered ‘forbidden’ literature for the first time when he read Ulysses by James Joyce. Nevertheless, his recollections of his first reading are not entirely consistent. In Little Wilson and Big God, he claims that one of the teachers at his school ‘had brought [Ulysses] back from illiberal Nazi Germany in the two-volume Odyssey Press edition’, while in Here Comes Everybody, his commentary on the works of Joyce, he gives a different account of how the novel came to be in his hands: ‘As a schoolboy I sneaked the two-volume Odyssey Press edition into England, cut up into sections and distributed all over my body.’

Whatever the truth of Burgess’s first encounter with Ulysses, it is clear that the logistical difficulties in reading it formed part of the experience. The novel was banned on its publication in 1922, in the United States and Britain, because of content deemed to be ‘obscene’. In particular, the censors in America objected to the ‘Nausicaa’ chapter, in which masturbation and sexual fantasy are depicted.

Despite the banning of Ulysses being lifted in Britain in 1936, the novel maintained a reputation for smut. Burgess remembers reading about Joyce’s death while he was cleaning windows in the army mess hall in 1941. His commanding officer only knew of Joyce because of his ‘dirty book’. Of his comrades’ attitude towards Joyce and ‘dirty books’, Burgess writes: ‘I have never felt inclined to condemn people who look for dirt in literature: looking for dirt, they might find something else. I do not think that those of my fellow-soldiers who read paperback pornography for masturbatory thrills saw that sort of stuff as of the same order as The Decameron or Joyce’s dirty book. In literature, they wanted confirmation that sexual desire, sexual exercise, and sexual obscenity were valid aspects of life.’

Burgess’s experiences of reading Ulysses informed his own novel writing, especially the mythic foundation of early novels such as The Worm and the Ring and A Vision of Battlements. Joyce’s great book was also formative in developing his attitudes towards literary censorship and obscenity. Like his fellow soldiers, Burgess thought that literature had a duty to reflect all aspects of life, whether sexual, bodily, or emetic. Ulysses is all of these things, depicting childbirth, defecation, menstruation, and other vital human experiences which were deemed obscene by the censors.

For Burgess, Ulysses was a novel that used language in new and interesting ways, but this meant that it could be attacked as a ‘dirty book’. He writes: ‘It seems that the novelist who is interested in language is also interested in life — too interested, say the censors.’ This was something he felt was also true of A Clockwork Orange.

And yet Ulysses is not merely, as Burgess writes, ‘dirty words and descriptions of bodily functions’. Burgess argues that ‘the obscenity was a structural necessity, not an arbitrary device of casual shock. Ulysses is, in fact, remarkably chaste, though its unbanning encouraged unchaste authors to smear themselves with filth and indulge in orgies of spermatorrhoea and coprophagy.’

The literary value of Ulysses, claims Burgess, stands apart from its representations of so-called ‘obscene’ acts. Describing the power of the book in Here Comes Everybody, he writes: ‘It is a story about the need of people for each other, and Joyce regards this theme as so important that he has to borrow an epic form in which to tell it. The invocation of the Odyssey may reduce Ulysses to Bloom, but it also exalts Bloom to Ulysses.’

These ideas, which Burgess formed in the 1930s, developed throughout his career, but the core of his thinking remained the same: if art is to be successful it must reflect the world in its entirety, including the distasteful or obscene aspects. The fullest articulation of these ideas came in 1970, when Burgess gave a lecture on obscenity to the Maltese Library Association.