Anthony Burgess and Censorship: Vladimir Nabokov

-

Graham Foster

- 12th July 2018

-

category

- Banned Books

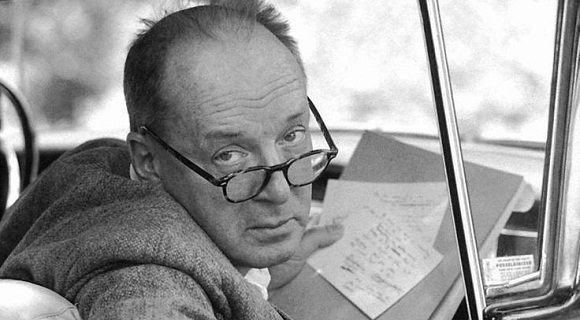

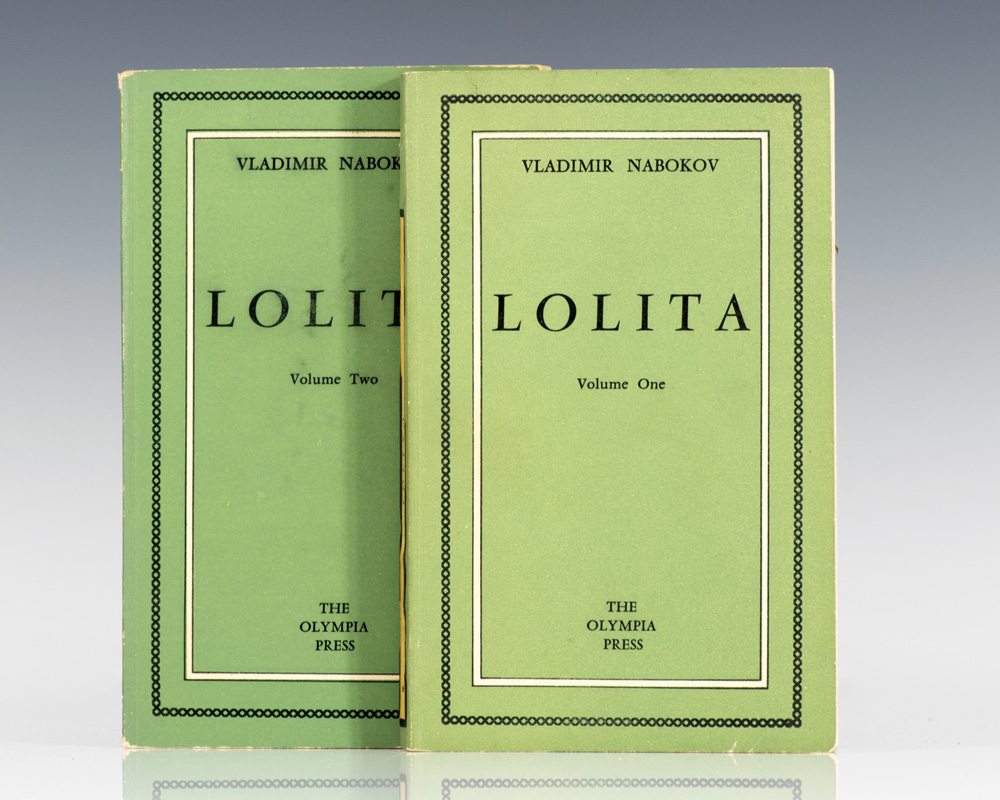

When the novel Lolita appeared in 1955, Vladimir Nabokov was a little known Russian novelist who had emigrated to the United States. After Olympia Press published the novel in Paris, Nabokov quickly became famous, not for his virtuosic control over language but for the scandal his novel had provoked.

Olympia Press was generally regarded as a publisher of borderline pornography, and by 1955 they had already attracted attention for publishing Henry Miller, Alexander Trocchi, and John Wilmot, the Earl of Rochester. Four years after Lolita, Olympia published Naked Lunch by William S. Burroughs to similar outrage. Nabokov’s novel was promptly banned in several European countries, including Britain.

Nabokov was uncompromising in his views of censorship, saying: ‘Any work of art is above censorship. But censorship of course depends on what you call a book. A book, a novel above all, is a work of art and must be above all restrictions.’

The life of Lolita, a novel about a man’s seduction of a 12 year-old girl, is remarkably similar to Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange (1962). Both novels were instrumental in galvanising the reputation of their authors; both novels were greeted by accusations of obscenity; and both novels went on to be filmed by Stanley Kubrick (Lolita in 1962, A Clockwork Orange in 1971). This comparison was also made by Burgess, who wrote: ‘It’s interesting to note that two of the most remarkable novels [of] this century – Joyce’s Ulysses and Nabokov’s Lolita – both earned moral condemnation, just like A Clockwork Orange. It seems that the novelist who is interested in language is also interested in life – too interested, say the censors.’

Burgess admired Nabokov’s work throughout the latter part of the twentieth century, naming Pale Fire (1962) and The Defence (1964) as two of his Ninety-Nine Novels: The Best in English Since 1939. The library at the Burgess Foundation has many copies of Nabokov’s fiction and nonfiction, including a copy of Lolita that Burgess inscribed to his first wife Lynne in 1959.

Nabokov’s influence on Burgess can be seen in novels such as Inside Mr Enderby (1963), in which the eponymous poet is a grotesque caricature of his creator, in much the same way that the erudite narrator Humbert Humbert is of Nabokov. A later Burgess novel, MF (1971), creates a fictional culture and language called Castitan, perhaps influenced by Nabokov’s invention of Zemblan in Pale Fire. Despite this evidence, Burgess claimed in 1972 that Nabokov was not much of an influence: ‘I’ve not been much influenced by Nabokov, nor do I intend to be. I was writing the way I write before I knew he existed. But I’ve not been impressed so much by another writer in the last decade or so.’

Burgess’s defence of Lolita largely paints Nabokov as a literary firebrand who was not afraid to experiment with language and to voice radical opinions about canonised classics. This view is reinforced when Burgess quotes Nabokov in his review of Lectures on Don Quixote (1983): ‘I remember with delight tearing apart Don Quixote, a cruel and crude old book, before six hundred students in Memorial Hall, much to the horror and embarrassment of some of my more conservative colleagues.’

This radical nature, suggests Burgess, can be seen in Nabokov’s novels, which should not be judged by any moral standard, but by their virtuosic literary art: ‘Those who thought [Lolita] pornographic knew only the title. If the book was shocking, it was stylistically so. People brought up on a sparer literary diet were appalled at the blend of pedantry and dandyism, the aristocratic chic which seemed unfitting on an age of plain prose and social commitment.’

If Burgess did not write much in defence of Lolita, perhaps this was because he didn’t need to. Once the novel was published in the United States in 1958, it sold 100,000 copies in three weeks. Capitalism is much better at defeating censorship than words, and Lolita’s success in America led to it being published freely in Europe the same year, leaving Australia as the only territory to maintain a ban (which was lifted in 1965).

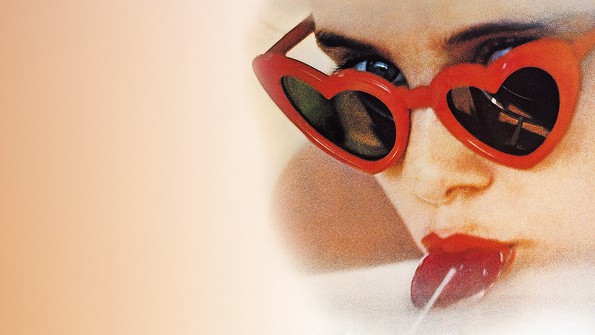

Despite these victories for free expression, Lolita would continue to come up against accusations of obscenity. While filming the first adaptation of the novel, the Production Code (known as the Hays Code) prevented Kubrick from filming the erotic scenes in Nabokov’s screenplay. This, coupled with the protests from Roman Catholic League of Decency, meant that he had to resort to using euphemism and oblique references to sex, such as a scene of Humbert painting Lolita’s toenails, and the famous image of Lolita sucking a lollipop. In 1997, the director Adrian Lyne had similar problems with his remake, starring Jeremy Irons as Humbert. Lyne also struggled to represent the novel’s erotic scenes, and resorted to using a body-double (and a strategically placed pillow) in order to circumvent the Child Pornography Prevention Act of 1995. The content of the film, and the murder of JonBenet Ramsay in 1996, made the film hard to market, and the release was delayed when the original distributor dropped out. After a very limited cinematic release, the film premiered widely on the television channel Showtime.

The exhibition ‘BANNED BOOKS: Anthony Burgess and Censorship’ runs at the Burgess Foundation until 30 September 2018 (weekdays 10am-3pm).