Anthony Burgess, Pamela Hansford Johnson and the Moors murders

-

Will Carr

- 9th July 2018

-

category

- Banned Books

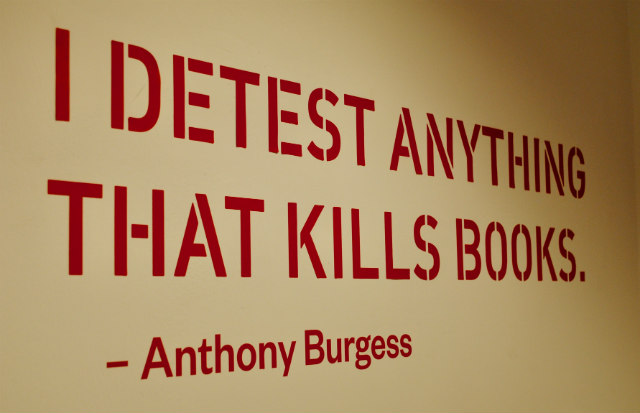

A year before Anthony Burgess moved to Malta in 1968, he became involved in a controversy about the banning of books closer to home. On the question of whether or not books should be suppressed because they might incite people to commit crimes, he robustly came down on the side of free expression.

The Moors murderers, Ian Brady and Myra Hindley, were convicted in 1966 of the killings and sexual assaults of three children and their trial was a tabloid sensation. A detail that emerged during the evidence used against Ian Brady was that he had owned a collection of books, and there was speculation that his reading habits may have in some way caused him to carry out his crimes.

The novelist Pamela Hansford Johnson attended the trial, and her book On Iniquity: Personal Reflections Arising Out of the Moors Murder Trial (1967) catalogues some of this grotesque library. There are works on fascism and the Nazis (Mein Kampf, Mosley Right or Wrong, The Mark of the Swastika); apparently erotic novels (Satin Heels and Stilettos, The Kiss of the Whip), and books about sado-masochism (The Pleasures of the Torture-Chamber, Orgies of Torture and Brutality), as well as two biographies of the Marquis de Sade. Johnson’s aim with her book about the trial was in part to try to ‘examine whether there are things which may encourage us in wickedness, or else break down those proper inhibitions which have hitherto kept the tendency to it under restraint’, and her argument suggests that the crimes committed by the owner of these particular books are prima facie evidence of the malign power that such books can have.

Johnson does not offer many solutions to this problem. She does not go so far as to demand more state censorship, but she contends that the mass circulation of certain books should be avoided (while not quite describing exactly how such a system should be developed and policed) – an argument that echoes the widely ridiculed question posed by Mervyn Griffiths-Jones at the Lady Chatterley’s Lover obscenity trial of 1960, in which it was asked whether D.H. Lawrence’s novel was one ‘that you would wish your wife or servants to read’. However, the moral questions raised by the Moors murders are arguably rather more serious than the sensitivities of novel-readers to Lawrence’s earthy prose, as Johnson is ultimately worried that a violent book might cause someone to commit actual violence themselves, and it is on this point that Johnson criticises Burgess directly. She quotes an article by him about Céline in which he states that ‘a world in which everyone is both torturer and victim [is] better than bourgeois death’: attacking Burgess as a ‘rhetorical poseur’, she accuses him of indulging in aesthetic responses to literature while ignoring its effects in the real world.

Burgess was stung by this. Johnson was a friend of his, to the extent that he dedicated his novel about Shakespeare Nothing Like The Sun (1964) to her, and he may have taken this attack somewhat personally. He responded in an article called ‘What is Pornography’, first published in the Spectator in 1967 and reprinted in his essay collection, Urgent Copy, in 1968. His position is that Brady’s reading of books about the Marquis de Sade had not caused him to commit crimes, but that Brady was predisposed to commit crimes anyway. Burgess argued:

‘A perverse nature can be stimulated by anything. Any book can be used as a pornographic instrument, even a great work of literature, if the mind that so uses it is off balance. I once found a small boy masturbating in the presence of the Victorian steel-engravings in a family Bible […] Ban the Marquis de Sade and you will also have to ban the Bible.’

Literature, for Burgess, does not engender harm but quite the opposite, enabling what he calls ‘reasonable catharsis’ in the reader, and banning it suppresses this beneficial effect – possibly, he speculates, going on to create more murderers. He concludes by worrying that censors ultimately over-reach themselves and all novelists should be uneasy at the expression of illiberal instincts by the establishment: ‘It might be anybody’s book [next]. It might be mine’.

In 99 Novels, Burgess selected Johnson’s 1962 novel An Error of Judgement – a study of a psychopathic young criminal murdered for the greater good by his doctor – as part of his selection of the best fiction published since 1939, published in 1984. He writes, not completely enthusiastically: ‘it is very much the task of this kind of novelist to present moral issues nakedly and leave readers with a sense of hopelessness at the difficulty of making any kind of decision at all. Alas, her style is undistinguished, even slipshod, but human concern shines through.’

With all that having been said, Burgess continued to grapple with the questions raised by Pamela Hansford Johnson until the end of his life. In one of his final articles for the Observer, ‘Stop the Clock on Violence’, published on 21 March 1993 and recently reprinted in The Ink Trade, he allows for the possibility that works of art – even his own works of art – might have effects that cannot, and perhaps even should be controlled. He is particularly exercised by the graphic immediacy of television and film, but acknowledges the power of the written word too:

‘At the time of the Moors Murders, when the killer Brady admitted that he might have been influenced by the Marquis de Sade’s Justine, the late Lady Snow [i.e. Pamela Hansford Johnson] said that if the burning of all the books in the world were necessary to save one child’s death, we should not hesitate to incendiarise (naturally, film would make a better blaze). That goes too far, but I begin to accept that, as a novelist, I belong to the ranks of the menacing. I used to regard myself as a harmless key-basher or pen-pusher.’

Fighting these battles through books and articles was one thing, but the censors were to catch up with Burgess for real on his move to Malta in 1968. Visit our Banned Books exhibition at the Engine House to discover more about how his library was seized by the Maltese authorities for its subversive and blasphemous content. A new edition of Obscenity and the Arts, Burgess’s lecture about the evils of censorship, which eventually led to his house on Malta being confiscated, is available from Pariah Press.