The Suppression of The Worm and the Ring

-

Graham Foster

- 11th September 2018

-

category

- Banned Books

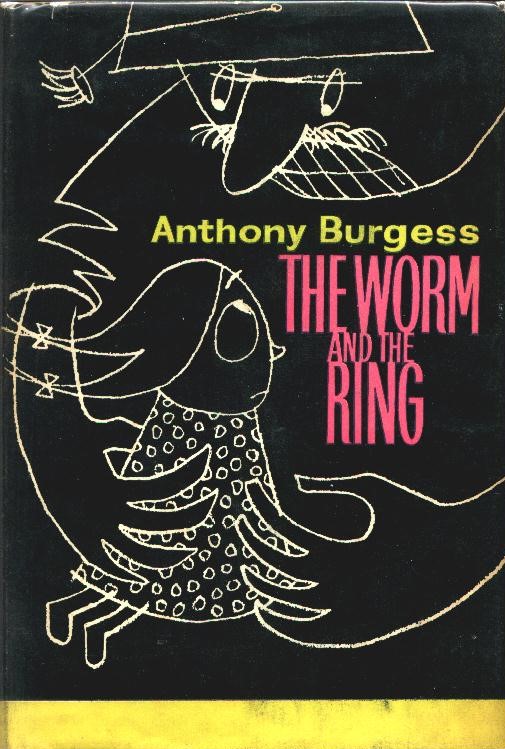

Although A Clockwork Orange is the most controversial of Anthony Burgess’s novels, with its themes of ultraviolence and state control, the book was ignored by the censors in most countries (not including Malta). But another Burgess novel, The Worm and the Ring, was suppressed not on the grounds of obscenity, but because it fell foul of the notorious English libel laws.

The Worm and the Ring, published in 1961, is a twentieth-century updating of Wagner’s Ring Cycle, itself based on the early German saga Nibelungenlied. The setting is an Oxfordshire grammar school and the book follows Christopher Howarth, a teacher who is unhappily married, in pursuit of a female teacher called Hilda Conner. A sub-plot deals with the discovery of a pupil’s stolen diary (in place of Wagner’s stolen ring), which reveals erotic fantasies of seduction by the school’s headmaster. At first glance, the setting and the classical foundation on which the novel is built do not indicate controversial material. Yet the book was withdrawn from sale a few months after publication.

Much of the novel was inspired by Burgess’s own experiences of teaching at Banbury Grammar School in the early 1950s. The first draft dates from 1954, and Banbury was fresh in his imagination when he began to write this book. The similarity between the novel’s setting and the real school attracted attention from people who saw themselves in the characters. One of Burgess’s colleagues, Moyna Morris, recognised herself in the fictional character of Hilda, who is the object of Howarth’s affections.

Burgess’s troubles with this novel began when the secretary of Banbury Grammar School, Miss Gwendoline Stella Bustin, noticed a character with a similarity to herself. Alice, the fictional school secretary, is an unmarried gossip who secretly lusts after the headmaster. This was too much of an insult for Gwen Bustin, who was an active member of the Banbury community and had served as the town’s mayor. Her lawyers wrote to the publisher, William Heinemann, notifying them that Miss Bustin intended to begin legal proceedings.

Burgess writes about this episode in You’ve Had Your Time, though he is careful to not admit any fault: ‘Miss Gwen Bustin […] had been eager to identify herself with the fictitious school secretary of the book. The strength of her case rested mainly on an onomastic coincidence: her own doctor had the same name as the doctor of the secretary in the novel. A letter from her lawyer made the standard accusation of malice, and my publisher promptly withdrew the unsold part of the edition. Now I was to await the delivery of a writ.’

Perhaps it is disingenuous of Burgess to describe the similarity of real life and the world of the novel as ‘coincidence’. Despite being an upstanding member of the community, Gwen Bustin was mocked by students at the school for being miserable, a quality which is also apparent in the character of Alice.

Burgess was heavily disappointed when Heinemann decided to remove the book from sale. All remaining hardback copies were withdrawn from bookshops and pulped, and the few copies that remained in circulation now change hands for thousands of pounds. It is obvious that Burgess did not understand the severity of the libel claim from Gwen Bustin’s lawyers, but Heinemann recognised the strength of the case and decided to make an out-of-court settlement.

A second hardback edition of the novel, bowdlerised by editors at Heinemann, was published as part of a uniform edition in 1970, but the original text has not appeared since its publication in 1961. The Worm and the Ring has not been published in America, and as yet there has been no paperback edition. Given that Gwen Bustin died in 1974, and other people referred to in the text are also no longer with us, in theory it would now be possible to reprint the novel in its original state.

This experience of legal suppression had an impact on Burgess’s future writing. In 1961 the text of his novel Devil of a State was altered before publication. Instead of being set in Brunei, where Burgess had taught at the Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin College, the location of the published book was moved to the fictional African state of Dunia. This and other changes were insisted on by Heinemann, to avoid any possible libel claims.

While the suppression of The Worm and the Ring was not undertaken for reasons of politics or obscenity, it nevertheless prevented Burgess’s work from reaching a wide audience. As his career developed, he came to believe that literature should reflect all aspects of life, whether obscene or emetic, and he was quick in his public defence of boundary-pushing novels such as Last Exit to Brooklyn by Hubert Selby, and Naked Lunch by William S. Burroughs. As he wrote in a review of Milan Kundera: ‘All literature, even when it is bad, is subversive.’

Burgess’s fullest statement against censorship appears in Obscenity and the Arts, the lecture he delivered to the Malta Library Association in June 1970, which is available in a new edition from Pariah Press.