A closer read: The Black Prince by Adam Roberts

-

Matthew Asprey Gear

- 22nd March 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

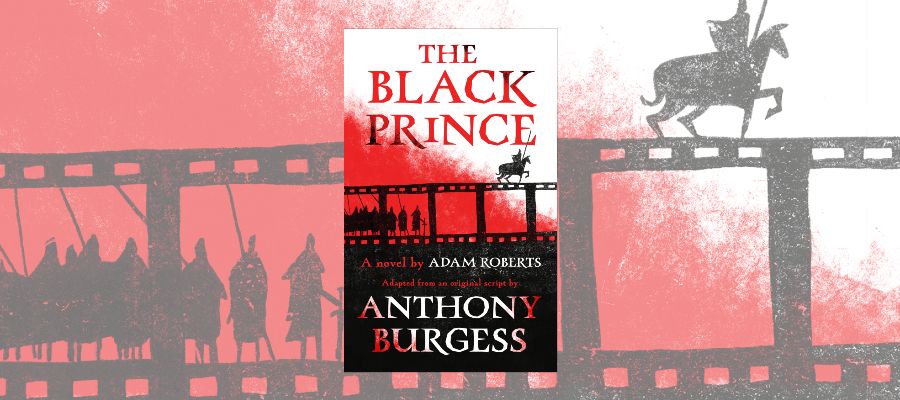

The Black Prince is a novel by Adam Roberts, adapted from an original script by Anthony Burgess and published by Unbound in 2018. Matthew Asprey Gear takes a closer look.

The 1960s was a fine decade for films on the Plantagenets and Tudors, from Becket (1964) and The Lion in Winter (1968) to A Man For All Seasons (1966) and Anne of the Thousand Days (1969). Anthony Burgess’s unproduced screenplay The Black Prince, written in 1970 for the producer Michael Holden, similarly attempts the English history genre, although Burgess’s work was not derived from a successful contemporary play. Less dialogue-dependent than those others and more panoramic, his screenplay is keener to drag us through the medieval muckheap of war, plague, and truly revolting meals. ‘Our aim is to diminish the pretentions of the fourteenth century,’ Burgess notes. He succeeds.

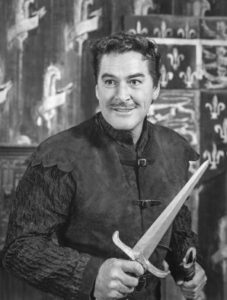

Edward Prince of Wales (1330-1376) was not unexplored dramatic material. The anonymous play Edward the Third (1596), with the Black Prince in a crucial role, probably used Will Shakespeare as a script doctor. Errol Flynn (pictured) had more recently swashbuckled across France in The Dark Avenger (1955) with about the same level of historical accuracy.

The Black Prince shares several historical plot points with its plausibly Shakespearean antecedent, such as the death of the blind King John of Bohemia at Crécy and King Edward’s reprieve of the six citizens of Calais. However, Burgess’s conception is firmly anti-heroic, showing war as hell on earth and taking the mask off chivalry. ‘It means there are two kinds of people,’ Burgess’s Black Prince explains, ‘those who are human and those who are no better than animals.’

The Black Prince shares several historical plot points with its plausibly Shakespearean antecedent, such as the death of the blind King John of Bohemia at Crécy and King Edward’s reprieve of the six citizens of Calais. However, Burgess’s conception is firmly anti-heroic, showing war as hell on earth and taking the mask off chivalry. ‘It means there are two kinds of people,’ Burgess’s Black Prince explains, ‘those who are human and those who are no better than animals.’

I’m not convinced the script would have made it to the screen unscathed. It’s easy to imagine a script doctor being called in to reshape the material into a more commercial epic: think Omar Sharif, Super Panavision 70, and the Yugoslavian army moonlighting in chain mail. As it turned out, The Black Prince never got that far. Notes in the archive suggest Burgess was not paid for his work.

Undaunted, he proposed a novel on the same subject in a 1973 interview with the Paris Review. An ever-resourceful freelancer, he would rework many of his unused commissioned scripts into experimental novels. The End of the World News (1982) intercuts three: a disaster movie scenario, a biographical teleplay, and an opera libretto. The Shakespeare film musical Will (also known as The Bawdy Bard) was incorporated into the plot of Enderby’s Dark Lady (1984). A mini-series, Attila, became the little-known novella ‘Hun’ (1989).

The revived Black Prince was to borrow the intentionally anachronistic format of John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. trilogy (1930-1936). This was a curious notion, as Burgess had already expressed doubts about the U.S.A. approach with its alternating ‘potted biographies … newsreels with headline-montages, italicised prose-lyrics, slabs of bald narrative, typography having a field-day.’ Reviewing Dos Passos’s quasi-sequel Midcentury in 1961, Burgess said that ‘the Dos Passos techniques seem only viable’ for ‘old drama in new costumes’ and were ‘incapable of new development.’

In any case, talking publicly about the planned Prince Edward novel seems to have relieved Burgess of the urge to write it. This recalls his warning about novels evaporating in Irish pub chat before they could be written down (another grimy historical novel, It is the Miller’s Daughter, had evaporated after Burgess allowed a few early chapters to appear in periodicals in the late 1960s).

Fifty years on, and in Burgess’s absence, The Black Prince has found a worthy successor. Adam Roberts has taken Burgess’s ninety-page screenplay and expanded it with impressive zest into that notional novel. It’s an unlikely pudding — Anthony Burgess-style wordplay mixed with Bernard Cornwell-style battle gore, poured into the Dos Passos mould — but Roberts’ novel actually makes a pretty good case for the validity of the U.S.A. approach. More so, in fact, than does the largely forgotten U.S.A. itself.

This new Black Prince is by design a stop-start narrative of Prince Edward’s career with extended asides that drift between biography and short story. The Black Prince is known for chivalry yet wages war as a psychopath — a sadistic torturer, rapist, and mass killer. Along the way we spend chapters with such figures as his wife Joan of Kent, the renegade biblical translator John Wycliff, and the French King Jean le Bon. Roberts has clearly boned up on his medieval history, because the details of the period are visceral, sordid, and convincing. He moves things along in a engaging style reminiscent of Burgess without becoming mere pastiche, revelling in Joycean compound words (‘duskdark’, ‘maggotthreaded’, ‘tremblearsed’), a plethora of what Martin Amis once described as ‘garlicky puns’, and the occasional unattributed quotation from John Boorman’s Zardoz. It’s a lot of fun.

Roberts is not the first writer to transform a Burgess script into a novel. In the golden age of the biblical TV miniseries, Burgess published eccentric book versions of his own teleplays — Moses the Lawgiver as an epic poem; Jesus of Nazareth and A.D. as sometimes heretical prose novels.

Roberts is not the first writer to transform a Burgess script into a novel. In the golden age of the biblical TV miniseries, Burgess published eccentric book versions of his own teleplays — Moses the Lawgiver as an epic poem; Jesus of Nazareth and A.D. as sometimes heretical prose novels.

Nevertheless, on each occasion his producer Vincenzo Labella turned elsewhere for an official tie-in book. Thomas Keneally, William Barclay, and Kirk Mitchell were respectively assigned the lucrative hackwork of making novels from teleplay drafts that had already borne the hand of an intervening script doctor (sometimes the devout Labella himself). As a result we’ve been left with rival novels descending from the same basic Burgess urtexts: a sober Authorised Version, you might say, beside Burgess’s belatedly published, vaguely retitled, Wycliffian heresy.

Although Burgess surely lamented the windfall of tie-in paperback sales, this way he avoided having to assign his copyright to such entities as Proctor & Gamble Productions, Inc., which in 1985 added A.D. to its regular production of Pampers and anti-dandruff shampoo.

The archives of the International Anthony Burgess Foundation are filled with unproduced screenplays, adaptations as well as original Burgess stories (albeit frequently closely based on historical sources). Some, such as Schreber (also known as The Brain Killers), have in recent years been adapted into BBC radio dramas. His unused script for The Spy Who Loved Me, ludicrously overflowing with 1970s excess, may one day provide the plot of a parodic spy novel; Donald E. Westlake’s Forever and a Death (2017), a rewrite of a Bond script, emerged from a similar process. Other dormant scripts, such as Uncle Ludwig and Cyrus the Great, suggest that Roberts’ enjoyable experiment need not be a one-off.

Matthew Asprey Gear is the author of Moseby Confidential: Arthur Penn’s Night Moves and the Rise of Neo-Noir (2019) and At the End of the Street in the Shadow: Orson Welles and the City (2016). He is presently writing a book about Anthony Burgess’s screen career.