A Long Trip to Teatime, or Edgar’s Adventures in Edenborough

2015 marks the 150th anniversary of the publication of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). The first tale of Alice’s adventures was followed six years later by Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871). Both novels proved immediately popular and continue to inspire readers, writers and artists alike.

Anthony Burgess created his own through-the-looking-glass tale, A Long Trip to Teatime, in 1976, and a draft of this forms part of the Burgess Foundation’s archive. The novel tells the story of a young boy called Edgar, who, wishing he could escape from a lesson about Anglo-Saxon kings, vanishes through the inkwell in his school desk and has a series of adventures while searching for a route home in time for tea. It was to be the first of two children’s novels by Burgess, which were both richly illustrated by Fulvio Testa.

A Long Trip to Teatime is not merely a fantasy for children. Although Burgess stops short of writing nonsense literature as such, he nevertheless experiments with several techniques commonly used in the genre in order to subvert ordinary language conventions and logical reasoning. Fantastical words populate the text – ‘There was a load of old rubbish in the corner – bucolics and eclogues and Barclays and sylviuses and economics and bagehots and darwins and ector and kays and seneschals, all very dusty’ – and seemingly logical arguments are extended to illogical conclusions. A snake argues that it is possible to know less than nothing about somebody, because ‘minus one is less than nothing’, and more than everything, since the biggest number there is is ‘about the same as everything’ and ‘’And I,’ said the snake, ‘I I I would be able to add one more. And one more. And one more. So, you see, I know more than everything.’

Elsewhere in the novel, reasoning follows a circular pattern that reveals the arbitrariness of its beginning. Posed with a riddle by an all-knowing screen – ‘EXPLAIN HOW IT IS THAT PEOPLE CAN BOTH LIE AND NOT LIE AT THE SAME TIME’ – Edgar answers: ‘King Solomon said that all men are liars, but King Solomon was a man, therefore he was a liar, therefore he was not telling the truth, therefore all men are not liars, but King Solomon was a man, therefore he was not a liar, therefore he was telling the truth when he said that all men are liars, but King Solomon was a man, therefore he was a liar, therefore he was not telling the truth when he said that…’

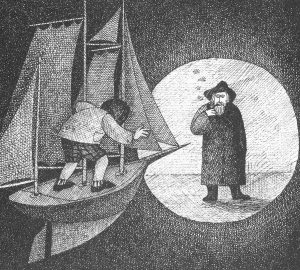

Burgess also includes puns and word play – a noted astronomer is called Stella Cistern – and, like Carroll, writes dream-jokes that are difficult, if not impossible, to render in other languages: one of two sailors whom Edgar meets gives his name as ‘Boniface, if you’re at all by way of being the least mite interested. Some say as it’s really Bonny Face and others as it’s really Bony Face, but there’s not one bone in my etchy omo as you can see, save for the sniffer perhaps, so I plump for the other meaning.’ Later, an echo is released from a drawer and calls ‘Aye aye. I. Eye’.

At times Burgess appears to quote Carroll directly. When Edgar assumes that the mouse, Albert, is also a prisoner in the castle, Albert replies ‘Stuff and nonsense’, echoing Alice’s response to the Queen of Hearts. Burgess does not, however, draw inspiration solely from Carroll. He includes verse inspired by the literary nonsense writer, Edward Lear – about whom Burgess subsequently wrote a proposed film script – and also acknowledges a debt to James Joyce. J. S. Atherton points out in his 1977 review that Joyce writes of a ‘hubbub caused in Edenborough’ in Finnegans Wake and Burgess’s Edgar must pass through Edenborough before he can reach teatime. Burgess himself writes in ‘All About Alice’ (Unesco Courier, June 1982) that ‘What, with Carroll, begins as a joke ends, in Joyce, as the most serious attempt ever made to show how the dreaming mind operates.’

When writing A Long Trip to Teatime Burgess adopted a technique that he had used previously in Nothing Like the Sun (1964) and Napoleon Symphony (1974). Using what he describes in his autobiography as ‘aleatory means’ he contrives his plot in part by selecting words at random from a reference book: many of Edgar’s adventures are associated with ‘E’ and derived by Burgess from encyclopaedia entries beginning with that letter. The novel begins with Edgar being taught by Mr Eadmer about the Anglo-Saxon kings, Edmund Ironside, Edward the Confessor, Edward the Elder and Edward the Martyr; after vanishing down the inkwell, he is put ashore on Easter Island to the sound of Easter bells; and among the tourists’ guide books in Edenborough are those describing the statue of Pierce Egan, a miniature El Dorado, a lecture by Ralph Emerson, and the story of the witch of Endor.

Burgess sums up ‘the appeal of the Alice books is to the creative imagination, by which space and time can become plastic and language itself diverted from the everyday course of straightforward communication.’ By creating a dream-world in his own novel, Burgess is able to play with language, logic and meaning in a similarly creative and imaginative way. He is careful to remind us however that what occurs in dreams is seldom wholly nonsense. It is only when, thanks to Albert the mouse, Edgar understands the Theory of Relativity that he can escape from his prison: space and time are relative, just as words in a sentence are modified by each other and the experience of the reader. ‘’The nitrogen isotope 14N has a half-life of 5730 years.’ is obviously sense, but it is sense that I have to take on trust. I would not dare to say that it is nonsense.’ (Anthony Burgess, ‘Let’s Talk Nonsense’, New York Times, 9 August 1987).