Burgess and D.H. Lawrence

-

Graham Foster

- 9th July 2019

-

category

- Blog Posts

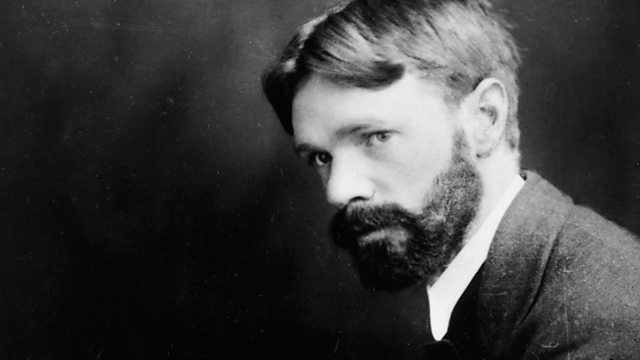

Anthony Burgess enjoyed comparing himself to other novelists, poets and playwrights. He sometimes spoke of himself as belonging to a group of writers who had emerged from provincial cities and had, through talent and persistence, made their mark on the British literary establishment. In his biography of Shakespeare, for example, Burgess suggests that, like Shakespeare, he had grown up some distance away from the cultural centre and become famous despite his humble origins. Burgess’s provincial Catholic background is visible, too, in his writing about James Joyce, who escaped from his bankrupt family in Dublin and (like Burgess) took himself into exile to write revolutionary novels for a world audience. The same might be said of D.H. Lawrence, who grew up in a coal-mining community in Eastwood, Nottinghamshire, before finding his way out through literature.

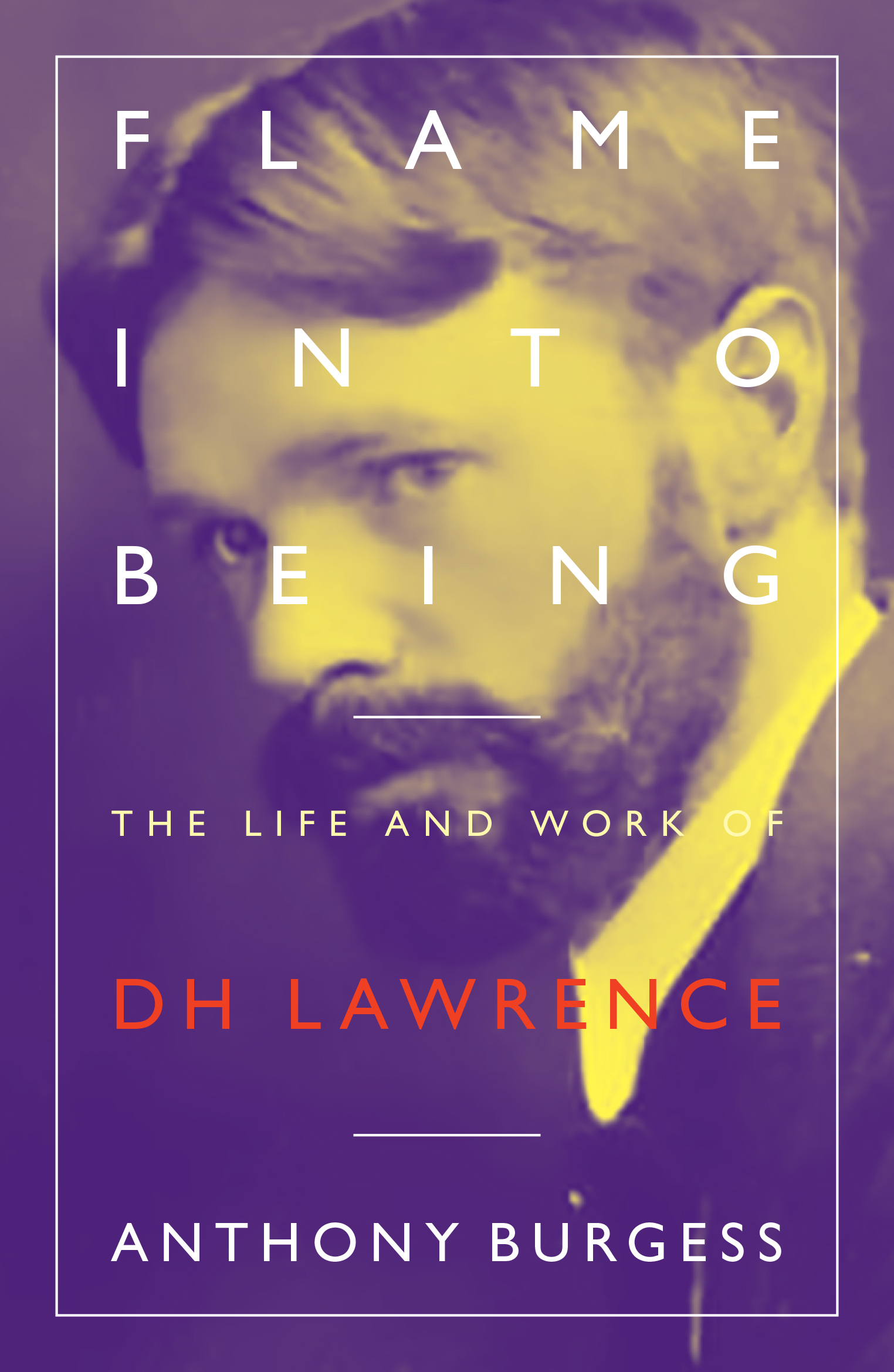

Burgess’s sympathy with D.H. Lawrence comes into focus in Flame into Being: The Life and Work of D.H. Lawrence (1985). He makes his affinities with Lawrence clear at the outset: ‘As the son of a Nottinghamshire coal miner he was not born into the literary establishment and had to prevail against those who were.’ As a writer, Burgess was drawn to London and recognised it as ‘the heart of culture’, yet he felt it lacked the more robust atmosphere of Manchester or Nottingham.

Throughout Flame Into Being, Burgess is keen to foreground the idea that he and Lawrence have things in common. He writes: ‘In old age I wake up with surprise to find myself in the situation Lawrence chose in his youth — namely that of British writer in exile (married, incidentally, to a foreign aristocrat), who feels more at home by the Mediterranean than by the Thames or the Irwell.’ The reference here is to his second wife, Liliana Macellari, who laid claim to the title of the Contessa Pasi della Pergola. When writing about Liana, Burgess forgets to mention that the Italian aristocracy had been abolished, and that such titles were no longer recognised under the law.

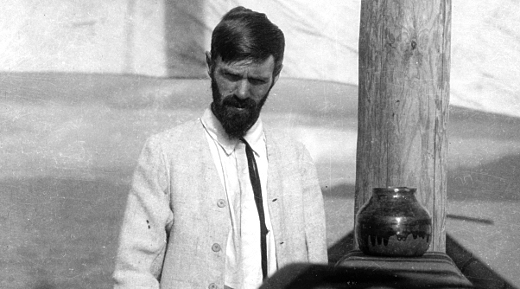

Lawrence left England after his books were banned and his paintings confiscated by the police. His wife, Freida, was German — a distant cousin of Manfred von Richthofen, the German fighter pilot known as the ‘Red Baron’. Lawrence’s association with Frieda had caused suspicion during the First World War, and the couple left England shortly after peace had been declared. Lawrence moved to Italy in 1919, from where he made trips to Malta, among other places. Burgess left Britain after he married Liana in 1968, and they travelled through Europe, eventually sailing from Italy to Malta.

Even as Burgess draws these parallels between himself and Lawrence, he must have been aware that their lives and modes of expression were rather different. He writes about a debt to Lawrence, but he adds: ‘This is not a literary debt — at least, not in the sense that I have ever wished to write like Lawrence. I admire his intransigence, and I sympathise with his sufferings on behalf of free expression.’

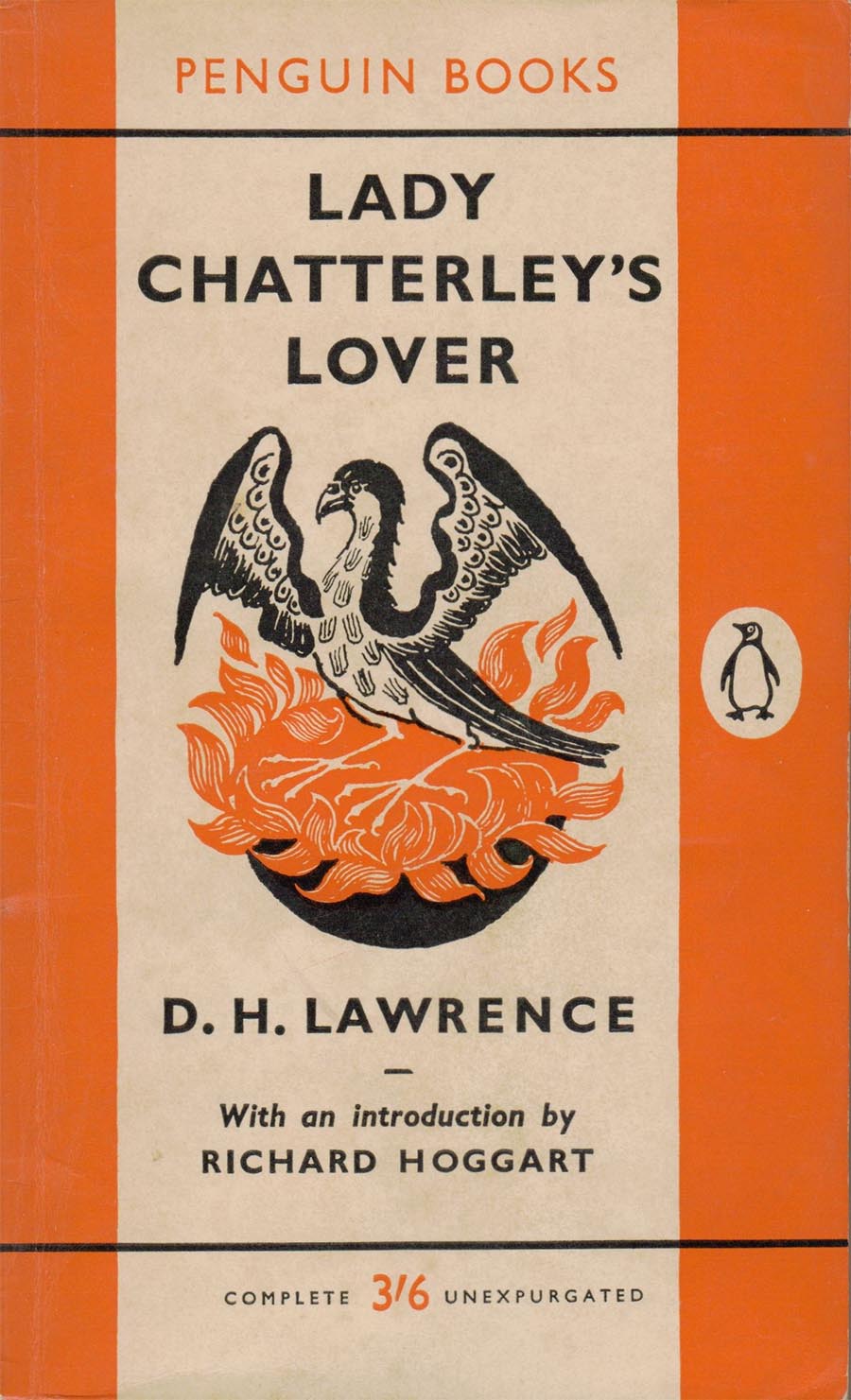

Free expression provides a strong point of connection between Burgess and Lawrence. Throughout the 1960s, Burgess developed his arguments against the banning of so-called ‘obscene’ literature. He reviewed The Naked Lunch by William Burroughs for the Guardian in 1964 and wrote a defence of Hubert Selby’s Last Exit to Brooklyn when the book was put on trial in 1968. Burgess’s attitude towards censorship was formed when he was a schoolboy in the 1930s, and he claimed to have read an illicit copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which was banned until 1960. He writes: ‘We were inflamed with a desire to get hold of those books not merely because they were outlawed, but because the reactionary or popular press hammered them so relentlessly.’ After reading Lady Chatterley, Burgess said that he had ‘got Lawrence the sex-man out of the way […] and was free to read him seriously.’

Burgess disagreed with the critical orthodoxy that ‘You cannot be a Joycean and a Lawrentian as well.’ By the time he came to write Flame into Being in 1985, his attention had moved away from Joyce. He wrote Blooms of Dublin, a musical based on Ulysses, in 1982, and he did not return to Joyce in a serious way after that date. His renewed engagement with Lawrence in the 1980s unlocked a mode of writing that Burgess had found difficult until that point. He began an autobiography in 1977 but could not find a way to complete it. Having read Lawrence’s novels about his youth in Nottinghamshire, Burgess was encouraged to return to the project of writing about his own early years. His novel The Pianoplayers (1986) is his first sustained attempt to describe the Manchester of the 1920s and 1930s. This book was followed in 1987 and 1990 by the two volumes of his memoirs, Little Wilson and Big God and You’ve Had Your Time. In retrospect, it is possible to see that Flame Into Being has a claim to be regarded as the first in an important series of late autobiographical works.

If, as Burgess says, Lawrence’s aim was to ‘penetrate to the heart of life’ with his writing, the same might also be said of Burgess. Where Lawrence was subversive in his honest depictions of human love and sexuality, Burgess worked to subvert traditional ideas about the nature of good and evil. Although Burgess and Lawrence could not be further apart in terms of literary style, the aims and subjects of their writing often ran on parallel lines.

The new edition of Flame Into Being — the first to appear in more than 30 years — provides an opportunity to relish some of Burgess’s best critical and biographical writing. Along with the biographies of Shakespeare, Ernest Hemingway and James Joyce, Flame Into Being allows new readers to see an unexpected side of Burgess as a gifted and entertaining non-fiction writer.

Flame into Being is published by Galileo. Click here for more details.