Anthony Burgess and James Bond

-

Andrew Biswell

- 30th November 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

The departure of Daniel Craig from the role of James Bond marks the end of the latest phase in the long-running film series. This blog post looks at some of Anthony Burgess’s responses to Ian Fleming’s most celebrated and enduring fictional character.

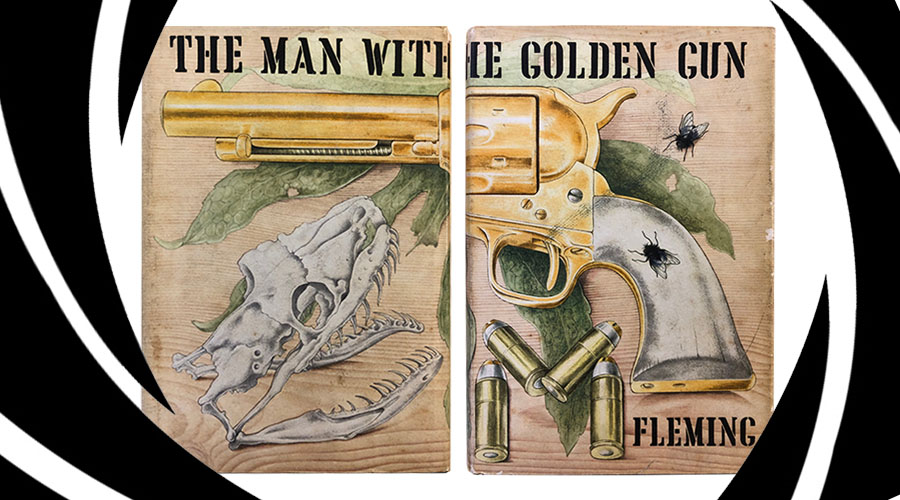

When Fleming died on 12 August 1964 he had not yet completed The Man With the Golden Gun. Kingsley Amis, a friend of Burgess and an admirer of his early writing, was invited to complete the manuscript of this final James Bond adventure, which was published in April 1965. We know that Burgess read The Man With the Golden Gun because he was invited to talk about it on BBC radio in 1966. A copy of the first edition survives in his book collection [front and back covers pictured below].

Amis went on to write the first posthumous Bond novel, published in 1968 under the pseudonym ‘Robert Markham’. This was Colonel Sun, an exciting tale about a sinister Communist mastermind who kidnaps ‘M’ and threatens to start a Third World War by blowing up some diplomats who have gathered for a secret conference on a Greek island. Amis was a Bond aficionado who had previously written a non-fiction book, The James Bond Dossier, as an extended homage to Fleming’s hero.

But Amis was not alone in wanting to cash in on the success of Fleming’s espionage series. Burgess also took a keen interest in spy thrillers of the Cold War. In his book about the state of the novel in the 1960s, The Novel Now, he includes a well-informed discussion of recent spy fiction, and he he claims that his friend Graham Greene, in books such as The Third Man, had exerted a strong influence on other genre writers such as John le Carré.

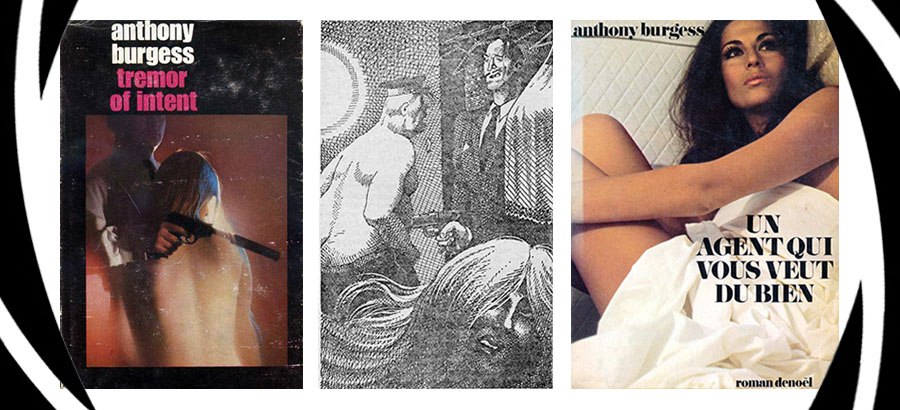

In 1966 Heinemann published one of the strangest novels Burgess ever wrote: Tremor of Intent, subtitled ‘An eschatological spy novel’. Set in a boarding school in Manchester, on a Baltic cruise ship, and in an unnamed country somewhere in Eastern Europe, Burgess’s novel involves a British secret agent named Hillier who is sent on a mission to bring back his former school friend, Edwin Roper, a rocket scientist who has defected to the Soviet Union.

Tremor of Intent features entertaining parodies of the standard set-pieces familiar to readers of Fleming’s novels: there is an epic bout of sex with an enemy agent, described in the involuted style of James Joyce’s Ulysses, and a confrontation with a gastronomic villain who challenges Hillier to an eating and drinking contest, the winner of which will gain a small fortune. It is as if the green baize card tables of Fleming’s Casino Royale had been replaced by a wine list and a well-stocked sweet trolley. Burgess set out to demonstrate that it was possible to describe the pleasures of the flesh without resorting to the kinds of cliché that critics often associated with Fleming’s popular style of fiction.

Tremor of Intent was favourably received by critics. Vernon Scannell commented in the Times Literary Supplement that ‘Burgess often writes like Nabokov, with the same energy and delight in language, the same constant awareness of nuance and ambiguity.’ William Pritchard, writing in the Partisan Review, drew comparisons between Burgess and his secret agent protagonist, claiming that both were ‘good technicians, superb at languages, agile, light-fingered, cool.’

Sadly, the critical reception of Burgess’s novel did not translate into large sales, although there were translations into French and Danish shortly after publication. In the second volume of his autobiography, You’ve Had Your Time, Burgess recalls that copies of the French edition were confiscated by the office of state censorship in Malta, where he was living, because the front cover showed a semi-nude woman under a bed sheet.

Burgess’s next encounter with James Bond came in 1975, when he was commissioned, along with various other screenwriters, to write a new script for The Spy Who Loved Me. Fleming’s original novel of this title was considered unsuitable for film adaptation, since the story, which does not concern spies or spying, is narrated by a young woman, and Bond himself appears only briefly towards the end of the book. The reviews of Fleming’s book had been so disappointing that the author would not allow any paperback edition during his lifetime.

Burgess invents a totally new plot for his screenplay — a clinic in Switzerland is turning celebrities into human bombs, and there is a conspiracy to blow up Queen Elizabeth II at Sydney Opera House — but it is unlikely that the producers of the Bond franchise gave any serious thought to filming it. The best moment occurs in a fight scene in a Chinese restaurant: one of the baddies is thrown into a cauldron of boiling water, at which point Bond pauses to add a dash of soy sauce. It’s easy to imagine Roger Moore doing this, and raising an ironic eyebrow to camera.

In 1987, to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of Terence Young’s film version of Dr No, Burgess was asked to write a new introduction for a series of Bond reprints published by Coronet. This is his major statement about Fleming’s novels, in which he argues that Bond has acquired the same mythical status as another fictional crime-fighter, Sherlock Holmes, who can never die because he never lived. While Burgess admired the ‘colossal villains’ to be found in Bond adventures — antagonists such as Hugo Drax, Dr No, Blofeld, and Goldfinger — he argued that Fleming’s characters were not as sophisticated as Shakespeare’s. He regarded Bond as a survivor from a different age ‘when it was not dangerous to smoke sixty cigarettes a day.’ Nevertheless, despite the formulaic plots and aggressive heterosexuality of the Fleming novels, Burgess concluded that James Bond was still ‘a hero we need’ because of his knowledge of the world: ‘the fast car, the correct recipe for a vodka martini, a dinner and a bridge game at Blade’s, the names of superior toilet articles.’

In 1987, to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of Terence Young’s film version of Dr No, Burgess was asked to write a new introduction for a series of Bond reprints published by Coronet. This is his major statement about Fleming’s novels, in which he argues that Bond has acquired the same mythical status as another fictional crime-fighter, Sherlock Holmes, who can never die because he never lived. While Burgess admired the ‘colossal villains’ to be found in Bond adventures — antagonists such as Hugo Drax, Dr No, Blofeld, and Goldfinger — he argued that Fleming’s characters were not as sophisticated as Shakespeare’s. He regarded Bond as a survivor from a different age ‘when it was not dangerous to smoke sixty cigarettes a day.’ Nevertheless, despite the formulaic plots and aggressive heterosexuality of the Fleming novels, Burgess concluded that James Bond was still ‘a hero we need’ because of his knowledge of the world: ‘the fast car, the correct recipe for a vodka martini, a dinner and a bridge game at Blade’s, the names of superior toilet articles.’

Writing about James Bond in Ninety-Nine Novels, Burgess said: ‘Fleming raised the standard of the popular story of espionage through good writing and the creation of a government agent who is sufficiently complicated to compel our interest over a whole series of adventures.’ He added that the films were ‘inferior entertainment to the books.’

While we were writing this post, we spotted this on Instagram: