Anthony Burgess and John Osborne’s The Entertainer

-

Will Carr

- 14th May 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

John Osborne’s 1956 play Look Back in Anger inspired the term ‘angry young men’ to describe a group of writers whose uncompromising and accessible works reflected a disillusionment with British society in the post-war period. Their world was run-down and meagre, and its protagonists were trapped in unfulfilled lives, resenting authority figures whose pretentiousness was often satirised.

Philip Larkin, Kingsley Amis, Alan Sillitoe and Colin Wilson were all part of this group, though the writers themselves largely rejected the label. Anthony Burgess, while he corresponded with these writers and reviewed their work positively, was himself not quite an ‘angry young man’, however. From a slightly older generation than John Osborne and working away from England in Malaya and Brunei in the late 1950s, his alienation was expressed in other ways, including the creation of his dystopias A Clockwork Orange and The Wanting Seed.

Burgess expressed a cautious admiration for Look Back in Anger, describing it in his 1979 survey They Wrote in English as Osborne’s ‘masterpiece’. His assessment was that the play

expressed with considerable power the disaffection of a sector of the British population which had previously had no real voice — the ‘angry young men’ of the provincial lower middle class, bitter at the hypocrisy of church, and state and at the stranglehold on society of the patrician Establishment, filled with a hopeless nostalgia for a virile romantic England.

Burgess’s own writing shares some of these preoccupations. Reviewing Osborne’s autobiography A Better Class of Person in 1981, Burgess developed this idea, connecting a nostalgia for Edwardian England with the ‘compassion’ that he finds in Osborne’s plays.

This is especially evident in The Entertainer, his ‘lament for the old traditions of the music hall’. This 1957 play has as its main character Archie Rice, a failing comedian and singer striving to emulate his father Billy Rice, a retired music-hall star. Archie’s limp comic patter and old-fashioned songs are contrasted with the remembered glories of the past, with the decline of Britain itself represented as a kind of crumbling theatre. The play starred Laurence Olivier and was a major success, with sell-out crowds in London and New York, and was adapted for cinema in 1960.

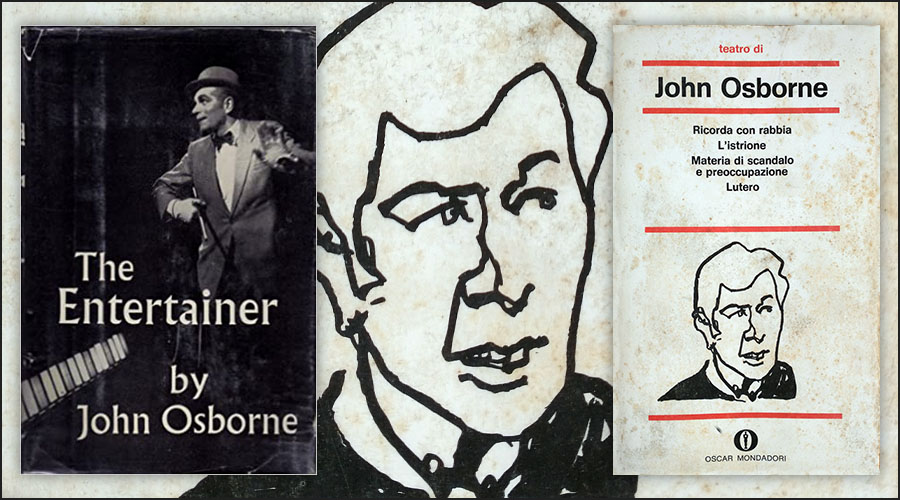

Burgess wrote in a 1989 article that Olivier was ‘superb in the role’ and suggests that he saw and enjoyed both the film and the play. His most sustained engagement with The Entertainer was in around 1971, while living in Rome, where he and his wife Liana appear to have been part of a proposed production (in Italian, L’istrione).

Looking at Burgess and Liana’s copy of L’istrione, translated into Italian by Amleto Micozzi and which is in the book collection at the Burgess Foundation, it is clear that they worked on the text together as it is annotated in both of their hands. Liana has made corrections to the Italian on a number of pages, inserting words and recasting sentences. Burgess has made changes to a mention of Due città (A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens), and suggests replacing a reference to the English actor Pat Campbell with the French actor Sarah Bernhardt: perhaps these alterations are meant to assist an Italian audience.

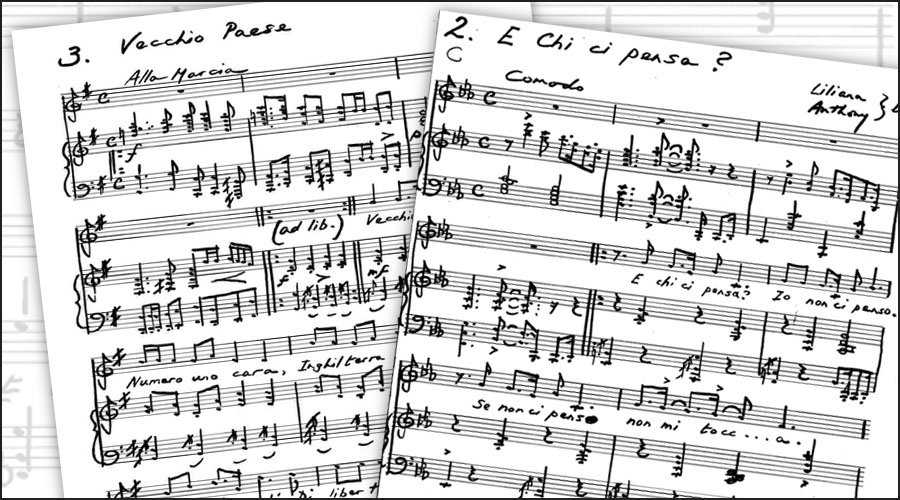

The Osborne play has original musical numbers by John Addison, and the lyrics to these appear in English in the Italian text that Burgess and Liana used. Again for the benefit of an Italian audience – and perhaps also as he wrote that the originals were ‘ghastly’ in his article about Laurence Olivier – Burgess replaced these songs with four new musical numbers for voice and piano, and the new lyrics in his handwritten score are given in Italian. Liana Burgess is credited alongside him on the manuscript and it seems likely that they created these works together.

Burgess would return to themes of popular entertainment in 1977, when he wrote the first draft of his novel, The Pianoplayers. Drawing on his own experiences of silent cinemas and the music hall in the 1920s and 1930s, like The Entertainer his novel contains elements of nostalgia for a lost era. The protagonist’s father is also called Billy, whose great skill as a pianoplayer is no longer required by the modern world. Similarly to Osborne’s Billy Rice, he retains dignity and stateliness even while his world fades away around him.

No records have been found of an Italian production of L’istrione ever having taken place with Burgess and Liana’s involvement. However, the premieres of two of Burgess’s lively and entertaining songs for L’istrione, ‘Vecchio Paese’ and ‘E chi ci pensa?’ (given the titles ‘Number one’s the only one for me’ and ‘Why should I care?’ respectively in the original play) took place as part of a special concert of music for voice and piano by Timothy Parker-Langston and Ewan Gilford recorded at the Burgess Foundation in March 2021. Watch this below.