Anthony Burgess and Molly Bloom: a reconstructed radio talk

-

Burgess Foundation

- 16th June 2015

-

category

- Blog Posts

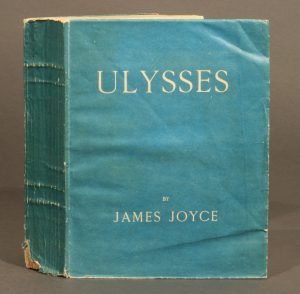

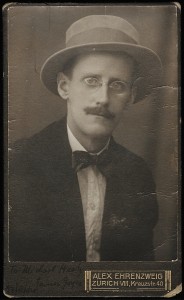

To celebrate Bloomsday (16 June), the Burgess Foundation is pleased to release a previously unpublished text by Anthony Burgess about his favourite novel, James Joyce’s Ulysses.

This radio talk, broadcast in 1960 under the title ‘My Favourite Heroine: Molly Bloom in Ulysses’, was discovered in the BBC Written Archives. The talk was commissioned by Jean Burns, the producer of Woman’s Hour. This was one of Anthony Burgess’s earliest appearances on British radio. He went on to appear regularly on Woman’s Hour over the next few years, speaking on a variety of women’s issues.

The original script seems to have been destroyed, along with many others like it, for space-saving reasons, but the BBC made a microfilm copy, from which a print-out has been extracted. The bottom of the first page was damaged, and about five lines of the text were illegible. Fortunately, the missing text occurs during Burgess’s plot summary of Ulysses, so the job of filling in the blanks is easier than it might otherwise have been.

The Foundation is grateful to an international panel of Burgess scholars for their advice in reconstructing the missing lines. One passage has proved impossible to reconstruct from the available evidence, and a few speculative words supplied by the editors have been inserted between square brackets. We would like to extend our thanks to Yves Buelens (Belgium), Dr Alan Shockley (Long Beach, USA), Dr Rob Spence (Edge Hill, UK), and Christopher Thurley (North Carolina) for dropping what they were doing to work on this text at short notice.

=====

WOMAN’S HOUR

PRODUCER: JEAN BURNS

“MY FAVOURITE HEROINE: MOLLY BLOOM IN ULYSSES” Anthony Burgess

TRANSMISSION: TUESDAY 29 NOVEMBER 1960

LIGHT PROGRAMME

Lead-In: And now, a favourite heroine. Anthony Burgess has chosen Molly Bloom from James Joyce’s book Ulysses and here he is to tell us why.

James Joyce’s Ulysses — which, like another book that’s recently been in the news, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, used to be banned — is a huge novel of nearly eight hundred big pages, and yet its scope is severely self-limited. We’re concerned with the actions and thoughts (mainly the thoughts) of a few people living in the city of Dublin on June 16th, 1904. The hero is Leopold Bloom, Hungarian-Jewish-Irish advertisement canvasser; the heroine is his wife Molly, a full-blown Irish rose from Gibraltar, daughter of a regular soldier, professional soprano, generous, unfaithful, foul-minded, sensual, a good mother, incorrigible, not too bad a wife really, of the earth earthy, adorable. To me, anyway.

Molly Bloom only makes two full-dress — or rather undress — appearances: on both occasions she’s in bed. We see her in the morning, “curling herself slowly with a snug sigh” and telling her husband to “hurry up with that tea. I’m parched.” Bloom brings her a postcard from their daughter Milly, who has a job as a photographer’s assistant in a seaside resort: Molly is pleased she’s doing well, for she’s a loving mother; Bloom also brings a letter from Molly’s lover of the day, Blazes Boylan, the sporty, flashy boss of a [concert touring] firm. Later that afternoon they are going to rehearse Love’s Old Sweet Song. Bloom is well aware of his wife’s infidelities: later he reflects that Boylan is just one more of a series that has included Bartell D’Arcy the tenor, Father Bernard Corrigan, a farmer at the Royal Dublin Society’s Horse Show, Maggot O’Reilly, the Lord Mayor of Dublin, an Italian organ-grinder, an unknown gentleman in the Gaiety Theatre, Dr Francis Grady, a boot-black at the General Post Office, and many others. Boylan won’t be the last of the series, either. Molly will never change. But Leopold Bloom doesn’t repine — a Jew of foreign origin living in a Catholic city of rabid nationalists, he’s learned to be philosophical about most things.

Throughout the long day of the book we keep on meeting Molly — not in the very substantial flesh, but in Bloom’s reveries and memories. It dawns on us that Molly is more mixed, more full of facets, than any other heroine in the history of fiction. She’s chronically unfaithful but her adultery seems to be merely an aspect of her love of life and her generosity. She’ll take in stray cats; later she’ll propose taking in the stray poet Stephen Dedalus, penniless, homeless, a portrait, incidentally, of the author himself. She loves food, stout, clothes, scandal, love, song. As Madame Marion Bloom, “Dublin’s prime favourite”, she has a full-bellied soprano voice which shrills, echoing in Bloom’s interior monologue, throughout the book.

We have to wait a long long while before we see Molly again — for the second and last time — in person. The last chapter is entirely hers, and what an incredible chapter it is. Words flow with the richness of gold or sewage for fifty huge pages, and there is not one single punctuation-mark. We hear her innermost thoughts as she lies awake in the small hours, her husband, the returned wanderer, snoring beside her with his head at the foot of the bed and his feet on the pillow. The frankness of Molly’s long inner monologue is still, after forty years, hair-raising, but it’s this frankness — the eternal woman without a scrap of social disguise — that makes her so endearing. We re-live her love affairs in all their sordid or splendid physical detail, but we also, most lovingly, review the virtues and faults of snorting Leopold. The endless turgid reverie embraces the whole of life — animal, mineral and vegetable — and an immense motherly love for it is disclosed. We slowly realize that Molly Bloom is not just a particular woman, not just an epitome of all women, but the earth itself — rolling on unchanging, dirty but full of flowers. Molly is everybody’s mother just as she’s everybody’s mistress, but she’s firmly rooted at home in an unbreakable marriage, sympathetic to her teenage daughter, mourning her long-dead son. God, flowers, fairy cakes from Lipton’s (“I love the smell of a rich big shop”), organ-grinder’s monkeys, opera, what happened on the canal bank, Gibraltar when she was a girl and a flower of the mountain, lover after lover but the conquering hero her own husband — the flood rolls on till sleep overtakes her, but her last words are “Yes yes yes” — a bell-chime of affirmation. Mephistophiles was the spirit that always denied; Molly Bloom is the body that always affirms.

She’s my favorite heroine because of her completeness. She isn’t one of the insipid golden-haired anaemic dolls of Charles Dickens; she’s a full mature woman, crammed with the imperfections of a being thoroughly alive. Only one other heroine of fiction can touch her — Madame Bovary. But Emma Bovary ultimately denies life and commits suicide, a thoroughly tragic figure. There is nothing tragic about Molly Bloom; she would never commit suicide, quite apart from her Church’s forbidding it. Life — full of stout, flowers, sunlight, fried fish, stray cats and poets, love-making and song — is too good for that. Much too good.

Text copyright © International Anthony Burgess Foundation, 2015.