Anthony Burgess at the Movies: A Night at the Opera (dir. Sam Wood, 1935) & Playtime (dir. Jacques Tati, 1967)

-

Graham Foster

- 20th November 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

To mark the 50th anniversary of the first release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, we present a weekly online series Anthony Burgess at the Movies in which we zoom in on Anthony Burgess’s interest in cinema.

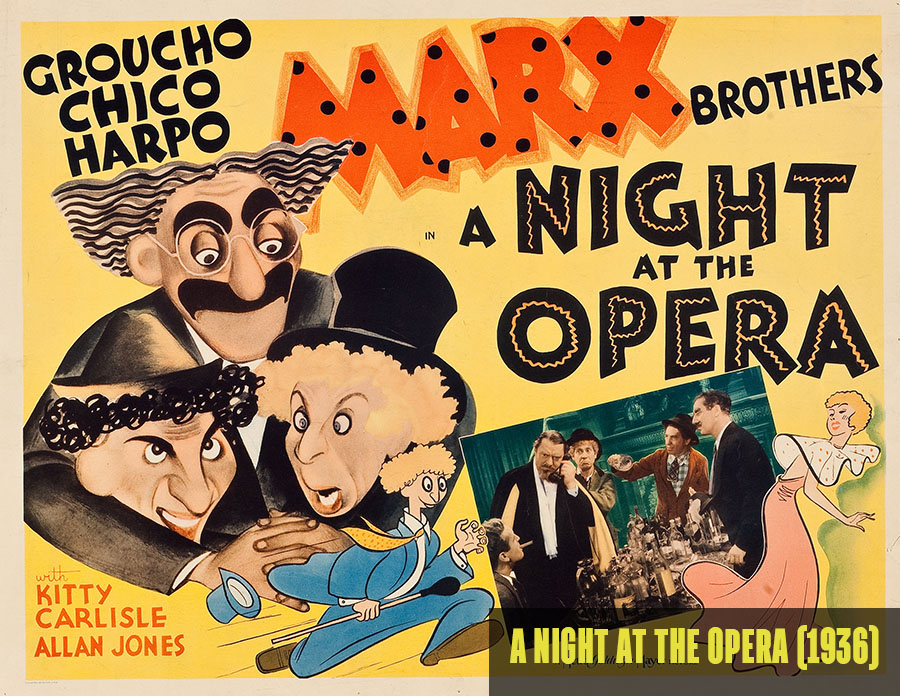

What Burgess says about A Night at the Opera: ‘A selection that anyone could have made, but I offer no apology. I love the Marx Brothers as the most flamboyant expression of dissidence that the West has ever known, and I think that this is the best thing they ever did. There is a classic scene (the one in which a ship’s cabin is turned into a black hole of Calcutta) whose comic ingenuity has never been matched. Groucho once gave me a cigar which I considered too precious to smoke. Somebody else smoked it when my back was turned.’

What Burgess says about Playtime: ‘This was Jacques Tati’s most ambitious film – plotless, very wide-screened, not generally popular and, so far as I know, never released in the United States. There are undoubted longueurs, but some bold chances are taken and some episodes are hilarious. For the first time in a comic film we have genuine counterpoint of action – two or three funny things going on simultaneously. The final episode – in which Paris, without undue exaggeration, is turned into a fairground – is quite brilliant.’

Anthony Burgess’s list of favourite films spans multiple eras and genres, but there are striking links between his choices that illuminate much about him and his work. The Marx Brothers’ A Night at the Opera and Jacques Tati’s Playtime are both innovative comedies that help reveal Burgess’s interest in humour and comedic writing.

A Night at the Opera, which tells a loose story of Otis P. Driftwood’s (Groucho Marx) attempts to sign an Italian opera singer to the New York Opera Company, is a series of comic sketches which incorporate sharp wit, slapstick and visual jokes. It is a further evolution of the Marx Brothers’ vaudeville act, and contains some of their most famous scenes including the crowding of a ship’s cabin and the on-the-fly editing of a contract that needs signing. It’s easy to see why Burgess was drawn to the Marx Brothers, with his own interest (and family history) in the music halls and entertainment industry of the North West of England. Their comedy is theatrical, with a chaotic sense of it being improvised (despite being carefully scripted).

Playtime is even more experimental, but can be seen as an evolution of the Marx Brothers’ precise style which is made to look chaotic. The film follows Jacques Tati’s famous character Monsieur Hulot as he arrives at a Paris office block for a meeting with a diplomat. The two men keep narrowly missing each other and Hulot gets lost in a modern city of glass and steel, eventually finding himself at the opening night of a restaurant which is still under construction. This plot does not do the film justice, and acts as the lightest framework for the onslaught of jokes, sight gags, slapstick, and satire. Tati’s Paris is visually stunning, a city rendered in uniform greys and minimalist interiors acting as a sharp criticism of the flattening effect commercialism has on the culture.

The fact that Burgess included these films on his list of favourites highlights the importance of humour in his creative life. Before he published his first novel, Burgess intended to be a serious writer, but he quickly found he could not maintain this seriousness. In an article about his first novel from 1981, he writes, ‘I discovered I was a funny writer, and I have never seen myself as anything but a creature of gloom and sobriety.’ Yet, he must have been aware that in his earliest cinema-going years, he was drawn to comedy, in particular the Marx Brothers, whose films he watched in the cinemas of Manchester in the 1920s and 1930s.

A Night at the Opera is an ensemble comedy full of large characters (despite the popular belief that Groucho is the star of the films) who interact within the defined parameters of an easily-recognisable situation (in the case of A Night at the Opera, the majority of the action takes place on a Transatlantic ship), and this is reflected in Burgess’s first book, Time for a Tiger. In this novel, there are compelling characters, such as the amiable drunk Nabby Adams, who interact in the defined setting of a hierarchical expatriate British community.

The Marx Brothers’ humour often punctures class structures, for example in A Night at the Opera Groucho is pitted against the snobs of the New York Opera Company. To some extent, Burgess’s writing mirrors this, and several of his books, such as his definitive comedies of the Enderby series, pit their protagonists against the uncultured and hostile elite, whether that is the judges of a poetry competition, Hollywood executives or even the army in books such as A Vision of Battlements and The Wanting Seed.

Playtime is also an ensemble film, but in a much looser way that A Night at the Opera. Filmed in 70mm extreme widescreen, Tati fills the frame with action, and this has the effect of taking the focus off Monsieur Hulot, who cannot be described as the protagonist of the film. This revolutionary approach to comedy can be seen as a radical evolution of the Marx Brothers’ visual humour, but it is more difficult to see how Tati’s masterwork influenced Burgess. Perhaps Burgess’s more experimental work in the 1970s shows the influence of Tati’s innovations, and books such as Napoleon Symphony experiment with a literary ‘widescreen’ with a proliferation of characters driving the story and multiple voices making up the narrative.

What is clear is that comedy was important both in Burgess’s fiction and in his public persona, and that comedy films were a vital part of his formative years growing up in Manchester. The timespan between A Night at the Opera and Playtime shows that this interest remained with him throughout the changing fashions of cinema.