Anthony Burgess at the Movies: I Vitelloni (dir. Federico Fellini, 1953)

-

Graham Foster

- 23rd October 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

To mark the 50th anniversary of the first release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, we present a weekly online series Anthony Burgess at the Movies in which we zoom in on Anthony Burgess’s interest in cinema.

What Burgess says: ‘I once asked John Simon, the New York film critic who seemed to hate most films, if there was any film he unreservedly liked. He unhesitatingly said: I Vitelloni. This is conceivably the best film Fellini ever made: it has the smell of urban Italy; its characterisation is deep but economical; it sums up an epoch, a social class, a debilitated Latin culture. It is beautifully shaped and one’s aesthetic response to it is highly complex.’

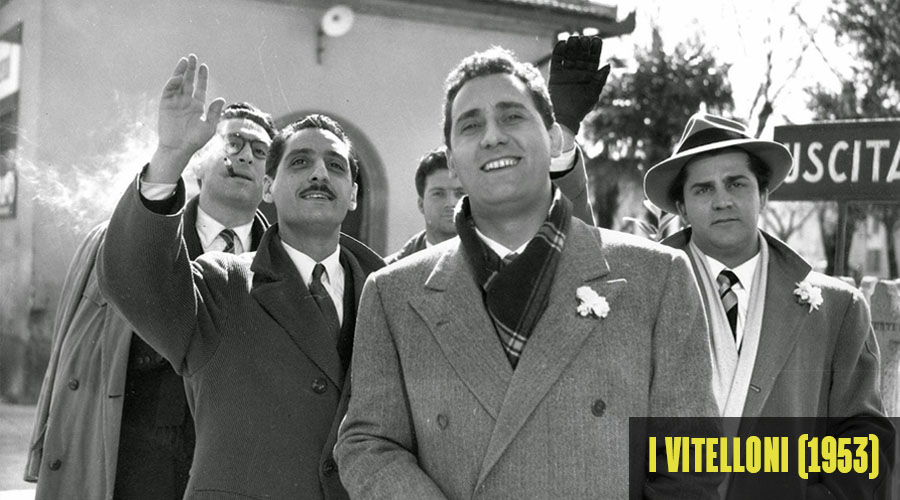

The meaning of the title of Federico Fellini’s film unlocks some of its themes. I Vitelloni literally means ‘the veal calves’, and refers to the five main characters who, like calves raised for veal, are growing fat through inaction. They are classic slackers, young men who have no direction, live with their parents and spend their days drinking, playing billiards and womanizing.

Although the film was released in 1953, right at the beginning of the era of the teenager, Fellini’s characters are older. They are in their late twenties and early thirties, adult men who are putting off the life of work and marriage and keeping their idealistic dreams alive. Riccardo (played by Fellini’s brother) wants to be a singer and actor, but it’s unclear whether he has the talent; Alberto is a daydreamer who is happy to be looked after by his mother; Leopoldo has ambitions to write for the stage but his plays are cliché-ridden and he is eventually taken advantage of by a homosexual actor; and Fausto is an inveterate womanizer who only wants to add notches to his bedpost. The only one of the vitelloni who is uncomfortable with this aimless life is Moraldo, who watches his friends with scepticism.

The film begins with Moraldo’s sister Sandrina fainting at a beauty pageant where she has just been crowned the winner. It is soon revealed that she is pregnant and the father is Fausto, who reacts by packing his suitcase and trying to run away to Milan. He is caught by his father and forced to marry Sandrina, but he cannot stop trying to seduce other women. In a particularly uncomfortable scene, he silently attempts to flirt with a woman in a cinema, even as he embraces his wife. His womanizing eventually catches up with him when he makes a pass at the wife of his boss, is rebuffed, and eventually fired.

As with other Fellini films, I Vitelloni deals with life in a provincial town, and the unwillingness of the young male characters to grow up. The early signs of Fellini’s recurrent themes and images can be seen in the film. For example, it ends without tying up the story neatly, and it contains images of the sea and the deserted night time streets of the small town. In one scene that points to the more experimental aspects of Fellini’s later films, a carnival morphs into a strange, surreal nightmare as one of the characters become drunkenly disorientated.

Burgess worked with Fellini in 1976, when he was hired by the director to be the English language consultant on Casanova. He was uncredited, but Fellini paid Burgess for his work with a new Steinway upright piano, which now resides in the Engine House at the Burgess Foundation in Manchester. Burgess recalled this experience in You’ve Had Your Time, the second volume of his autobiography:

I wrote acceptable synchronisable English for a number of producers in Rome. Fellini’s films were the easiest to dub. The master, reconciled to the impossibility of using microphone and camera in concert, used to insist that his actors justify the opening and shutting of their mouths by merely counting […] When I dubbed some lines for Fellini’s Casanova, I saw that the habit of post-synchronisation was imposing a limitation of techniques: there could not be too many close-ups.

Burgess referred to Fellini’s films in his fiction. Ronald Beard, the screenwriter protagonist of Beard’s Roman Women, sees Rome through the filter of La Dolce Vita, and he visits a restaurant called Rugantino, where ‘Anita Ekberg had once danced on a table in profound décolletage’ during the shooting of Fellini’s film.

I Vitelloni remains a captivating film that acts as a precursor to much of the fiction that was produced between the 1950s and the 1970s. The characters in Fellini’s film are among the first examples of post-war disaffected youth that would eventually evolve into the itinerant characters of Jack Kerouac’s beat novels, the ‘Angry Young Men’ depicted by Alan Sillitoe and John Osborne, and the droogs in Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange. In film, Fellini’s story inspired directors such as Martin Scorsese (Mean Streets), George Lucas (American Graffiti) and Joel Schumacher (St. Elmo’s Fire). Stanley Kubrick chose I Vitelloni as one of his ten favourite films for Cinema magazine in 1963.

It remains a fascinating film, showing the early promise of a director who came to be regarded as one of the most important in Italian cinema.