Anthony Burgess at the Movies: Things to Come (dir. William Cameron Menzies, 1936)

-

Will Carr

- 6th November 2021

-

category

- Blog Posts

To mark the 50th anniversary of the first release of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, we present a weekly online series Anthony Burgess at the Movies in which we zoom in on Anthony Burgess’s interest in cinema.

What Burgess says: ‘This [Alexander] Korda film of the middle 1930s has its faults – but it has two (perhaps irrelevant) features which never fail to move me: one is the excellence of the spoken English – which sometimes shows up the insufficiency of H.G. Wells’ dialogue – and the other is the music. Wells insisted that Arthur Bliss write this first, reversing the regular pattern, and that certain sequences be fitted to it in a ballet-like manner. It works, and its power has not diminished in the last half-century.’

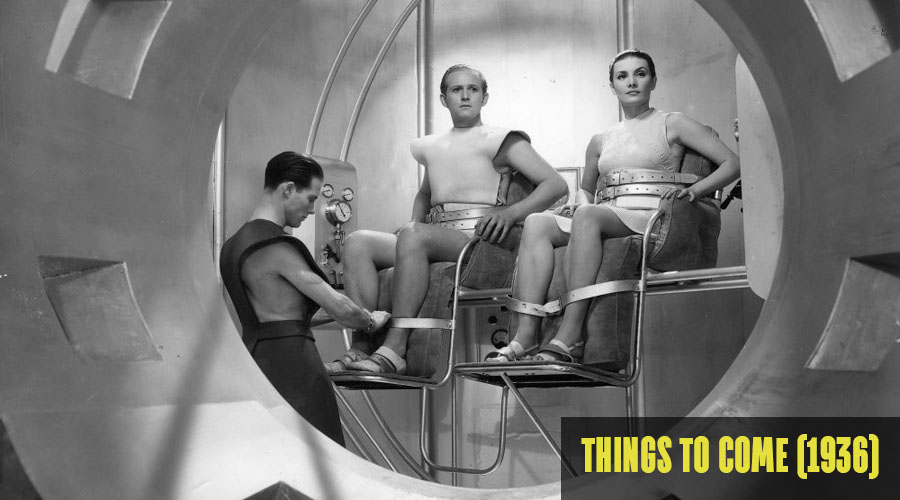

Things to Come is an epic science fiction film, presenting a dystopia caused by global conflict that is eventually turned into a utopia through technology. H.G. Wells wrote the screenplay, based on his own 1933 novel The Shape of Things to Come, and the director William Cameron Menzies used vast sets, innovative special effects and futuristic designs to make the film a spectacular vision of the future.

An avid cinema-goer from a young age, Burgess saw Things to Come on its first release. It made a strong impression on him, to the extent that he records in his autobiography that one of his first poems, ‘September 1938’, published in the Manchester University student magazine The Serpent, took its imagery of endless war and machines fighting each other from the film. For Burgess at that time Wells’s film seemed to be, as he puts it, ‘true prophecy’.

Things to Come begins under the dark skies of gathering war in the near future of 1940, with the peaceful inhabitants of ‘Everytown’ worrying about impending conflict. Suddenly, aerial bombardment begins and there is general mobilisation, and everybody’s lives are upended. The war then drags on for thirty years, and the reasons for the conflict are forgotten. A plague called ‘the Wandering Sickness’ has decimated the population, civilisation has collapsed, and local warlords have seized power and rule amidst the desolation. From this bleak low point, a gleaming visitor from what seems to be the future appears from the sky: John Cabal (Raymond Massey), who is a representative of a group called ‘Wings Over The World’ who have banded together to save humanity and restore order. Cabal is taken prisoner by a warlord (Ralph Richardson), but he is not concerned: huge planes from Wings Over The World soon arrive and drop sleep-bombs on the populace, enabling them to take charge without a shot being fired.

Fifty years later, and a bright new utopia has been created, with peace and harmony amidst enormous bright white buildings and with lots of people in uniforms. John Cabal’s great-grandson Oswald Cabal (again played by Raymond Massey) is about to launch a space rocket to spread civilisation beyond the Earth: a mob of anti-technology reactionaries attempt to stop him, but are easily circumvented. The film ends with an extravagant speech about the fundamental importance to humanity of progress: ‘Man must go on, conquest beyond conquest. First this little planet and its winds and ways. And then all the laws of mind and matter that restrain him. Then the planets about him and at last, out across immensity to the stars. […] It is all the universe or nothing! Which shall it be? Which shall it be?’

This action is set against Arthur Bliss’s sweeping score, which as Burgess says was written before the film was shot. Bliss was originally known as a modernist composer, but during the 1930s explored more romantic and traditional styles in the mode of Elgar. Working in collaboration with Wells, Bliss created a complete musical journey for Things to Come that captures the emotional range of the film from its dystopian wastelands to the noble quest of civilisation to prevail and establish a new society. The music was widely praised on the film’s release, and it survives outside the film as a concert suite for orchestra that is still played today. Arthur Bliss is well represented in Anthony Burgess’s vinyl collection, with three records of his music held in the Burgess Foundation archives.

The film received mixed reviews on release, with the uneven characterisation and tendency to descend into speech-making rather than convincing dialogue putting off some critics; Graham Greene, writing in The Spectator, felt the final utopian section in particular ‘peopled by beautiful idealistic scientists’ to be sentimental and unrealistic. Further, the techno-fascistic elements of Wells’s utopia are not hard to see. The vision of a militarised, highly organised, centrally controlled society in which the collective will subjugates the individual, coupled with what we now recognise as the trappings of a totalitarian state such as sleek uniforms, rallies and huge monolithic architecture, all make post-war appreciation of the film more difficult than Burgess’s first experience of it in the 1930s. We can speculate that these problems with the film perhaps inform Burgess’s later focus on the acting and the music in his short review and his suspicion that it does have its faults. Despite all this, however, Things To Come is still regarded as one of the most important science fiction works of the period and laid the foundations for later films such as Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Burgess’s assessment that ‘its power has not diminished’ still holds true.